He was a natural for Charleston. When Mike Lata left Atlanta’s Ciboulette in 1998 to become executive chef at Anson, he was already a staunch supporter of the farm-to-fork philosophy and a spokesperson for the Georgia organic produce movement.

The young phenom had been wooed for more than a year by a like-minded Glenn Roberts, then the mover and shaker behind the Balish family’s restaurant empire. Once Lata was on board, Roberts quickly planned a press weekend featuring the young chef preparing Lowcountry heritage foods and culminating with the state’s first out-of-house James Beard dinner.

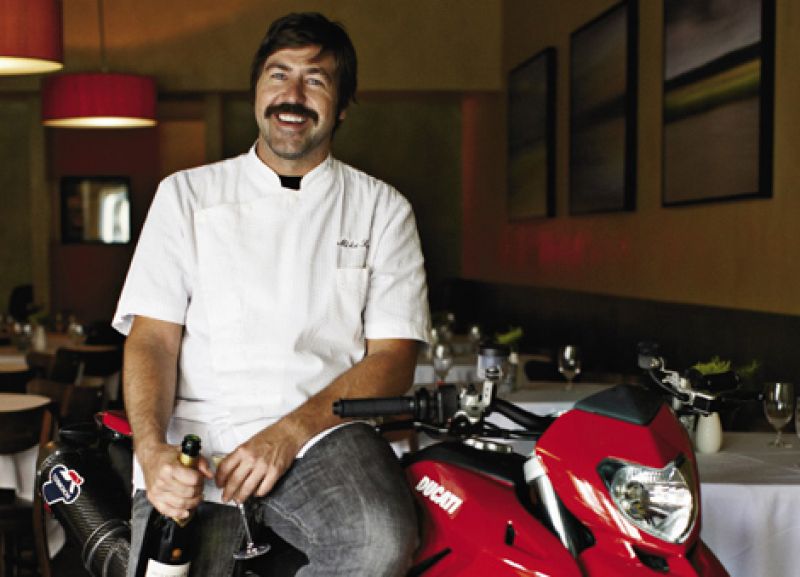

By 2003, Lata and his business partner and fellow Anson alum Adam Nemirow had opened FIG, which they describe as “one part retro diner, one part neighborhood café, one part elegant bistro.” The name, a nod to their philosophy “Food Is Good,” soon became symbolic for the cuisine. Though the dishes are composed, it’s done minimally, a style legendary chef Frank Stitt calls “capturing well the soul and flavor of local farmlands and waters.” However casual by design, the unassuming neighborhood eatery was quickly lauded in major publications ranging from Forbes to Gourmet.

Segue to May 2009. By the time Lata stepped off the stage after accepting the James Beard Award for Best Chef Southeast, his e-mail inbox and voice mail had crashed. It took days to wade through the congratulation messages. “In 2007, when I received the first nomination, I was so amazed I couldn’t cook for two days,” remembers Lata. “After I lost, I began to work for it, reaching out to people, traveling, politicking, always raising the bar at the restaurant.

“When you don’t win, you downplay it,” he continues. “This year I was ready to lose, but when I won, just for that moment, nothing else mattered. There is this sense of accomplishment that puts your mind and soul at ease. Then you go right back to thinking about how to better your restaurant!”

Lata and Nemirow are quite pleased with how far FIG has progressed. The Beard Award has increased the restaurant’s business substantially, so Lata tries to be in the kitchen five nights a week. “Our name’s out there now and people’s expectations are up. You have to deliver. Longevity and integrity is a tough combination that few can hold onto tightly. Complacency,” he grins, “is not an option.”

Charleston, which was simmering quietly on the culinary scene in the ’90s, received only one nod from the James Beard Awards in the first decade after its inception in 1990, and that went to Southern food pioneer Louis Osteen, called “the spiritual general of the new Charleston chefs” by The NY Times. Since the turn of the century, that recognition has been at a rolling boil with many chefs—and others in the industry—having captured their attention