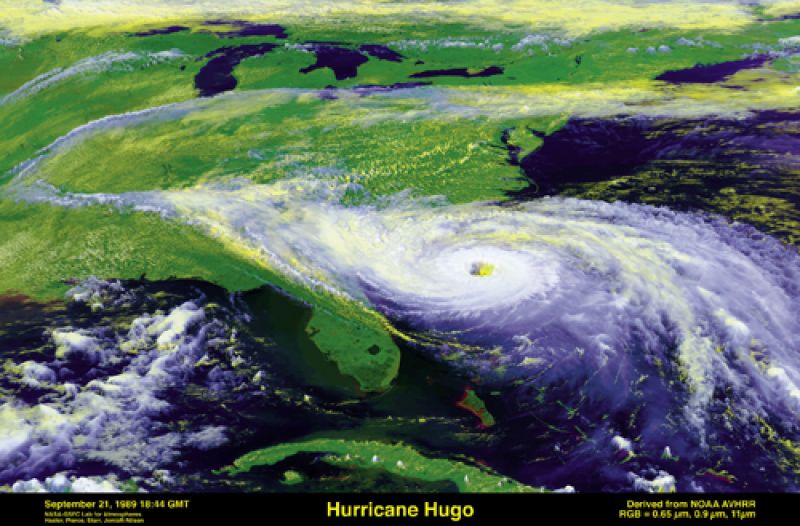

Born off Africa near the Cape Verde islands, Hugo first hit the Caribbean as a full-fledged force five hurricane with winds close to 190 mph. It then aimed straight for Charleston. The sheer size of the storm was enough to put terror in our hearts. Hugo was huge. At some 250 miles in circumference with a 40-mile-wide eye, the storm was as big as the state of South Carolina.

Even though Hugo weakened to a Category Four before it made landfall, it blasted the Lowcountry with such destructive force that residents awoke the next morning to a landscape that recalled Hiroshima. Entire neighborhoods were gone. It looked like we had been hit by a bomb, and we had—one of extreme wind and tidal surge. Hugo’s wind speed was officially measured at 137 mph, when the National Weather Service gauge broke. Shrimpers who rode out the storm on their boats speak of measuring gusts in the 160 to 180 mph range. Additionally, Hugo’s waters wreaked havoc, flooding the Charleston peninsula and completely covering the barrier islands. In the fishing village of McClellanville, the storm surge was nearly 20 feet high.

Hurricane Hugo left us stunned, in a state of shock and awe. Some 56,000 people were homeless, their houses either gone or in such disrepair that they were unlivable. There was no electricity. Water was undrinkable. Sewer systems were down. Incredibly, the telephones worked—sometimes. In less than 12 hours, Hugo had transformed our beautiful, tranquil Lowcountry into a war-torn, third-world country. It would take almost two years to rebuild.

Personal Experience

As Hugo neared the coast the afternoon of Thursday, September 21, I was battened down in my house in the Old Village area of Mount Pleasant. Grey, scudding clouds were whipping in from the east, bringing with them an uncommon sound: the roar of the surf on Sullivan’s Island far across the marsh. As the sun set, the sky turned a menacing reddish-orange, an eerie copper with tinges of green. I poured myself a Scotch, fed the dogs and cats, and took what would be the last warm shower for a long time.

For a while, it was okay to watch the storm’s building power from the porch. First came driving rain bands, with winds so strong that the drops flew by sideways and stung like buckshot on the skin. By dead dark, the night was howling with a relentless roar of thunder and lightning so constant it illuminated a sky wild with clouds racing by. Twice I saw the luminous greens, reds, and yellows of St. Elmo’s fire.

Once it became too dangerous to venture out, I measured the storm’s ferocity by sounds—the sickening moan of a tree being pulled from its roots; the startling shotgun POW! of a snapping limb that would then fly wild and slam savagely into the side of the house; the fingernails-on-blackboard screech of a neighbor’s tin roof being curled back and ripped from the rafters.

Finally, as Hugo closed in, the decibel level rose into one continuous scream—a ceaseless high-pitched whine fused with the thunderous growl of 100 freight trains. The barometric pressure dropped, and the cats began to howl, one so panicked it tried to claw its way up the wall. I checked the barometer. It registered 28.1, the lowest I’d ever seen. The needle pointed to the word “hurricane.” Hugo had arrived.

Get Out Now!!!

We Lowcountry folks had gone through hurricanes before. There had been Hurricane Hazel in 1954 and Gracie in ’59. We grew up knowing the importance of having boxes of candles, Sterno, canned food, water, and extra flashlight batteries on hand. Yet nothing in our experience prepared us for a storm with the intensity of Hugo.

Since then, tempests like Hurricane Andrew, Katrina, and, most recently, Superstorm Sandy have given us all a heavy drenching of reality when it comes to understanding the destructive power of hurricanes. But in 1989, it had been 20 years since the United States had experienced a major hurricane and 30 since Charleston had been visited by Gracie. Such a long lull between storms often breeds a sense of complacency.

Charleston-born and -bred Mayor Joseph P. Riley, Jr. had ridden out hurricanes before. He was here for Gracie, which had peak winds of 125 mph. “We had been watching Hugo since its inception,” Riley recalls. “But this was no Gracie. This was a Camille.”

As powerful a Category Five storm as nature can create, Hurricane Camille hit the Gulf Coast in 1969. Camille’s winds and 24-foot storm surge obliterated entire communities, vaporizing beachfront apartment complexes and high-rise hotels and killing 256 people, many of whom died because they refused to evacuate.

With Hugo making a beeline for Charleston, Riley contacted his Gulf Coast counterparts for advice. “They told me the most important thing was to order an early evacuation,” he says. “But they also told me that people would not leave simply because I asked them to. That we needed to somehow strike a balance between fear and panic. That I needed to raise the tenor in my voice to communicate that lives were at risk. After one of my televised messages, even my wife said, ‘Did you hear Joe’s voice? I’ve never heard it like that!’”

This near-panic set the tone for the days before Hugo hit. Local television and radio stations broadcast nonstop with evacuation instructions. Charleston County Council chair Linda Lombard was on camera constantly, shouting the message: “LEAVE! Leave NOW!” Likewise, the late Charlie Hall, weatherman for Channel Five since television’s inception and a paterfamilias to Charlestonians, pressed the urgency for evacuation.

“It means something when a person as trusted as Charlie Hall looks worried,” says McClellanville native and author William P. Baldwin. “We were planning on staying at our house in the village until one of Charlie Hall’s last reports. It was late in the afternoon, and the wind had already picked up. Hall said, ‘If you have not evacuated yet, don’t try. It’s too late. The storm is almost on us. Get to high ground if you can.’ When Hall ended the report tearfully, saying, ‘And may God bless your soul,’ that did it. We moved to a higher place.” Given the extremity of the storm surge in McClellanville, that decision likely saved their lives.

In Charleston, police went door to door in the peninsula’s low-lying communities, telling people to evacuate to Gaillard Auditorium. Yet even with a mandatory evacuation on the barrier islands of Folly Beach, Sullivan’s, and Isle of Palms, some people still hedged. “I was toying with the decision to evacuate until an Isle of Palms policeman came over in a boat and told us we had to go,” says Goat Island resident Don Thompson. “That clinched the decision.” For those who refused to leave, authorities asked for the names of next of kin. When Hugo’s waters wrenched Thompson’s house off its foundations and moved it 30 feet, he was riding out the storm in Columbia.

Sadly, 35 deaths in South Carolina were caused by Hurricane Hugo. Yet because people evacuated, very few died from the storm surge, the major cause of death in any hurricane. Not one person on the peninsula perished from rising waters. “If we did anything right,” says Mayor Riley about the evacuation process, “we got people out. We saved lives.”

Best Laid Plans

“Hurricanes are notoriously unpredictable,” explains Channel 2’s Rob Fowler, who was the new kid on the meteorological block when Hugo hit in 1989. “For a while, some models predicted that the storm might veer to the north towards Myrtle Beach,” he remembers. “As it turned out, Hugo never wavered. The storm was locked and loaded with Charleston in its sights. This was disastrous for places like McClellanville in the storm’s northeast quadrant, which takes the full brunt of the storm.”

McClellanville resident Randy McClure had decided to leave his house on the Intracoastal Waterway to ride out the storm in his real-estate office in the village on reasonably high ground. His wife and two children, the youngest of whom was only a few months old, were driving to Charlotte. At the last minute, seeing his wife’s concern, he chose to drive them Upstate himself. McClure, who served on the school board, knew the planned shelter at Lincoln High School was entirely inadequate. “I’d spent a good part of the days before Hugo hit calling the EOC [Emergency Operations Center] and explaining that the designated shelter at Lincoln High was a disaster waiting to happen,” he says, recalling the helplessness he felt trying to get them to change the location to the elementary school. “The elevation of the high school was only nine feet, three inches above sea level, and it was too close to the water. St. James Santee Elementary was further inland and had an elevation of 16 feet, five inches. The people at EOC kept telling me, ‘Yes sir, we’ll take care of it,’ or ‘We’re working on it.’ The last thing I did before we drove Upstate was stop at a pay phone and call EOC one more time. They assured me the change had been made.”

The shelter was never moved. That none of the some 600 people who spent the night of September 21st at Lincoln High were killed is one of Hugo’s miracles. Then-principal Jennings Austin was at the school during Hugo and recalls that people began settling in around 4 p.m.: “We weren’t real concerned at first. Even when the power went out around 9 p.m., leaving us in the spooky emergency lighting, it wasn’t so bad. We could hear the wind howling outside but the building was built as solid as a rock. We hoped that we might get through the night without incident.”

Around midnight, Austin was with deputy sheriff Charlie Dutart making a check of the school’s L-shaped building. Most of the people were in the cafeteria/auditorium at the end of one of two long halls. Austin and Dutart were at the far end of the other hall when water began seeping in. “When we first realized water was coming in, it was only up to our ankles,” he recalls. “In what seemed an instant, the water was up to our knees, then to our waists. Apparently it was pouring into the classrooms where the pressure had broken out the air-conditioning units. There was no way to get back to the cafeteria. If we were going to live, we needed to find a way out.”

Going into a classroom, the men grabbed an overhead projector from a table and tried to break the Plexiglas window. (The school’s old glass and wooden windows had been replaced earlier that summer.) It wouldn’t budge. After repeated attempts, the window finally broke. At this point, the water was chest-deep.

The men pushed outside into a raging chaos and started climbing up the building, away from the rising surge and onto the roof, only to be slammed down by the powerful winds. They ended up crawling on their bellies, barely sheltered by the two-foot-high wall bordering the roof, until they reached the higher cafeteria roof, where they laid down amidst some pipes. At one point, Austin says that he saw an entire brick house float by, carried by the swirling waters of the surge. “We could hear the screams of the people below us,” he says. “We were sure that if we were lucky enough to live through the night, we’d find 600 dead bodies in the cafeteria, drowned.”

In fact, those in the cafeteria were fighting a watery hell in darkness, doing everything possible to keep their heads above the rising waters. They frantically placed tables on tables, chairs on tables, finally crowding onto the stage area, where they repeated the stacking of tables and chairs and climbed atop, holding their babies and children overhead.

EMT paramedic George Metts was in the cafeteria and later described the scene in his official report: “The enormity of our situation was staggering. We were totally trapped…. We were on our own, the water was still rising, and those that could [get there] were packed like sardines on the stage.”

His group of 10 to 15 people consisted of women, children, and a few men. “I noticed a nearby woman trying to hold up two children,” he wrote. “I took one and held her above the water. She was a three-year-old named Tsara.... We stayed in chest-high water for several hours. I remember talking and singing to the child, trying to pass time.” Later, around 3 a.m., someone on the roof knocked out a top windowpane on the opposite wall. Only a few dared cross to safety. “I knew the women couldn’t swim across the cafeteria, and I knew I could not swim the distance with a three-year-old in tow, so I prayed along with everyone else,” remembers Metts. Finally at about four or five that morning, the water level lowered. Miraculously, no one in the cafeteria was seriously injured.

At first light, people began coming out of the school, and Austin and the men were able to climb off the roof. “It was joyous,” recalls Austin. “Everybody was hugging, grinning, even laughing. We were alive. We were standing in waist-deep water, but we had survived. What saved everybody inside the school were the new Plexiglas windows. They buckled with the stress of water pressure but held. Otherwise, water would have poured in and completely inundated the interior of the school.”

Deceptive Eye

The previous night as Hugo’s eye passed over Mount Pleasant, it brought a deceptive calm. For about a half hour, the winds stopped, and stars could be seen overhead. For some, this brought an opportunity to move to a safer place, yet it could prove perilous since once the eye passed, the winds, now from the west, would hit with even more savage fury. The second half of the hurricane also brought the storm surge.

In Mount Pleasant at their house off Rifle Range Road, Mary White and her sister, Laverne, had gone outside during the lull of the storm’s eye to search for a lost wallet. Suddenly they heard the roar of the surge coming towards them from Copahee Sound. They started running, keeping just ahead of the water, not stopping until they reached Highway 17, where they found refuge in a church. When they finally made it home the next morning, the house was intact. The surge, however, had wreaked havoc with the interior. There was even a shark in their living room.

Johnny Cleary was with his family at their farm at Buck Hall in Awendaw when he realized the house might not hold. “We felt like the three little pigs, running from the straw house to a stronger one,” he recalls. “The wind was insane. The ditch between the properties was being flooded by the surge and looked like rapids. I still can’t believe we made it.” Before Hugo, the houses had been sheltered by the deep woods of the Francis Marion National Forest. “The next day it looked like a bomb had hit,” says Cleary. “We could see for miles to the horizon because the trees had either been cut in half like broken matchsticks or were gone completely.” In fact, 1.3 million acres of forest had been destroyed—enough timber to build 660,000 new homes.

East Cooper resident Sammy Small had taken his motor cruiser up the Wando near Cainhoy to ride out the storm in safer waters. At the height of the storm, realizing he would have to abandon his sinking vessel, Small put on not one but three bright orange life vests. At least his family might be able to find his body afterwards, he thought. The next morning, he says that he stumbled through the marsh, amazed to be alive. Two men who had anchored their shrimp boat nearby had not been as lucky. Small found their bodies as he was trudging through the marsh to high land. The winds had been so strong they had blown the men’s clothes off. Their boat had been reduced to splinters, entirely destroyed.

On the peninsula, the surge had overflowed the city, turning narrow streets into raging rivers—a swirling mayhem of churning salt water, floating cars, downed trees, and flying debris from the pieces and parts of roofs and piazzas that had been blown into smithereens by the hurricane winds. Despite being surrounded by water, Roper Hospital was operating successfully under emergency power until the surge knocked out the fuel lines that powered the generators. Braving the winds and rising waters, boiler operator David Johns and co-worker Daniel Dyer spent the night taking turns going out into the storm, alternating every 30 minutes to wade through thigh-deep water to hand-pump fuel into the generators, thus keeping the hospital’s life-support machines, operating rooms, and emergency lights working. For protection, Johns duct-taped his hard hat to his head and looped a thick rope around his waist to keep from being blown or washed away. “We knew it had to be done,” Johns said later. “We were just there to do it.”

The Aftermath

The scope of Hugo’s destruction was as immense as the storm itself. Not only was the entire coastal region damaged from Edisto Island up to Myrtle Beach, the hurricane-force winds reached inland all the way to North Carolina. Meteorologists estimate that some 3,000 tornadoes were spawned as Hugo ripped a swath of destruction through the state. Twenty-nine of South Carolina’s 46 counties were declared disaster areas. More than 40 percent of the state was without power. Damages in the U.S. totaled $7 billion.

As the first line of defense against the sea, the barrier islands were hit particularly hard. Some of Folly’s front-beach homes were either entirely gone or reduced to sticks in the sand. All that remained of the famous fishing pier were pilings. The storm surge had completely inundated Sullivan’s Island and Isle of Palms, leaving both in shambles. There wasn’t even a way to reach them. The Isle of Palms Connector hadn’t been built yet, and the only passage to either island was across the Ben Sawyer Bridge, now inoperable, sitting with one end cockeyed in the water. Hugo’s winds had set the bridge spinning with such force that it had “uncorked” itself from its center holding post.

Because of the utter destruction on Sullivan’s Island and Isle of Palms, the authorities placed them off-limits, even to residents, as a matter of public safety. Homeowners became understandably upset when they couldn’t access their properties. Tempers flared. “I don’t think people had any way of comprehending how bad it was,” recalls former Sullivan’s Island mayor Carl Smith, who was on Town Council at the time. “I could hardly believe the extent of the devastation. It was like the island had been swept clean.

“I know it sounds cliché, but both islands were like a war zone,” he continues. “Some streets were gone; most were impassable and covered with sand and debris. There wasn’t any safe way onto Isle of Palms. The Breach Inlet bridge was intact, but the road to it on the Sullivan’s side had been washed away.

Every electrical line was down, and the gas lines were compromised. It was simply too dangerous for people to be there.” Even the council members weren’t allowed on the island; when they had their first meeting after the storm, it was by candlelight in the educational building of Mount Pleasant Presbyterian Church.

Indeed, most who were here the morning after Hugo couldn’t fully comprehend the extent of the storm’s destruction—or the massive cleanup ahead. Homes that hadn’t been demolished were often filled with mud, seaweed, and dead fish and held the telltale tide-line marks along their interior walls. Even the outlying communities of Summerville, Moncks Corner, and Georgetown were without electricity. Some people would be without power for more than a month. Water came out of the tap but was undrinkable. Streets were choked, impassable barriers of fallen trees, soggy mattresses, furniture, and unidentifiable pieces of houses. There was a dawn-to-dusk curfew. National Guardsmen were everywhere.

We were wrecked. Yet the community spirit after Hugo is, beside the awfulness of the hurricane itself, probably what most remember when asked to recall the storm. Despite the chaos, there was a wonderful pulling together that brought neighbors and strangers to work toward a common goal—and a common good.

“How’d you come out?” someone would ask. “You-all okay?

“Well, we lost the house, of course. A tree took the roof, and the rains got the rest of it. But we’re safe, and thank God, we’re alive. How about you? Anything I can do to help?”

The following months were ones of never-ending cleanup, executed to the rasping whines of chain saws and a sky filled with the incessant, clattering racket of emergency helicopters. Neighborhoods took on a circus-like appearance, with almost every other roof wreathed in garish blue plastic covering a gaping hole or missing shingles taken by the wind. Streets became canyons framed by seven-foot walls of debris.

On the Isle of Palms, a giant burn area was created in the location of the current county park to get rid of the refuse on the two islands. For months, a huge, towering inferno of burning trash was tended constantly as dump trucks rolled in, feeding the flames with pieces and parts of what had been our houses, gardens, trees—our lives. “It looked surreal,” recalls Thompson, the Goat Island resident whose home was deposited 30 feet from its foundation. “Like something out of Hades. Fires constantly going, big and small, and against the glowing embers you could see the people who tended the fires moving like shadows. It looked like Plato’s cave against a fiery hell.”

Attempts at looting and price gouging were swiftly quashed. When out-of-town carpetbaggers tried selling ice and bottled water for $10 a pop, they were stopped cold by Mayor Riley who made it abundantly clear: “We will NOT tolerate gouging.”

Despite efforts to stay positive and work toward a common good, Hugo undeniably took a toll on the psyche. Anxiety and tensions were high. Issues with insurance companies abounded, not only raising tempers but causing maddening delays in rebuilding. Just living amidst seemingly endless piles of debris was soul-crushing.

“With no power for so long, it became a very depressing thing to live through, that recovery,” recalls Channel Five news anchor Bill Sharpe, who was on the air almost nonstop before and after Hugo hit. “It affected us emotionally and physically. Our bodies hurt from working so hard to get things cleaned up. But it took an emotional toll as well. You saw it everywhere. Tempers flaring over minor things; arguments over nothing. But I know that my trying to help others through the information our station was providing on air helped me get through it. And I think that feeling of people helping others was pervasive throughout the whole Lowcountry.”

Next Time?

Shortly after Hugo, a friend of mine foolishly stated with grand authority, “Hugo was the storm of the century. We won’t see another like it for 100 years.” If that were only true. There have been times when the Lowcountry has had as many as three hurricane strikes in a single year. Historically, we’re just as likely to go through periods with years-long gaps between storms. As Rob Fowler says, “The question isn’t if but when the next storm will hit us.” There will always be another hurricane.

Are we prepared? Since Hugo—very much because of Hugo—building codes are more stringent than before. Also, the science of hurricane prediction is so highly sophisticated today that computer models can sometimes accurately predict the direction of a storm weeks before it makes landfall. “It’s not perfect,” says Fowler. “It is never going to be. But the models continually amaze me with their precision. They give us weather casters a lot more confidence that what we are telling people is accurate.”

When asked if they would stay the next time a major storm threatens, everyone interviewed for this article answered with an emphatic “No!” They would not only evacuate, but evacuate early. Yet Fowler brings up an interesting point: what percent of current Lowcountry residents experienced Hugo? “When I speak to groups, I ask for a show of hands to see how many went through Hugo. In the years right after the storm, at least two-thirds raised their hands. That number now is down to about one-third,” he says. “A lot of these people are new to the Lowcountry. They have never experienced anything like a hurricane before. Some weren’t even born when Hugo came through.”

Looking at the tall stands of trees, beautiful homes, and sweeping views of the Lowcountry today, it is almost impossible to believe that 25 years ago these same vistas were scenes of utter destruction. Yet nature rebuilds; trees grow back. In large measure because of Hugo insurance money, Charleston came out gleaming with revitalized glory. Communities mushroomed in places where only farms and forests had been before. All seems secure and safe—an enviable place to call home.

And indeed it is—just don’t let down your guard during the months of June through November. Some day the winds will blow again, and the tides will rise. Heed the warnings. Keep those flashlight batteries on the ready. And if the authorities say “evacuate,” get the hell out of town.