The first group of Huguenots arrived on the ship Richmond in April 1680

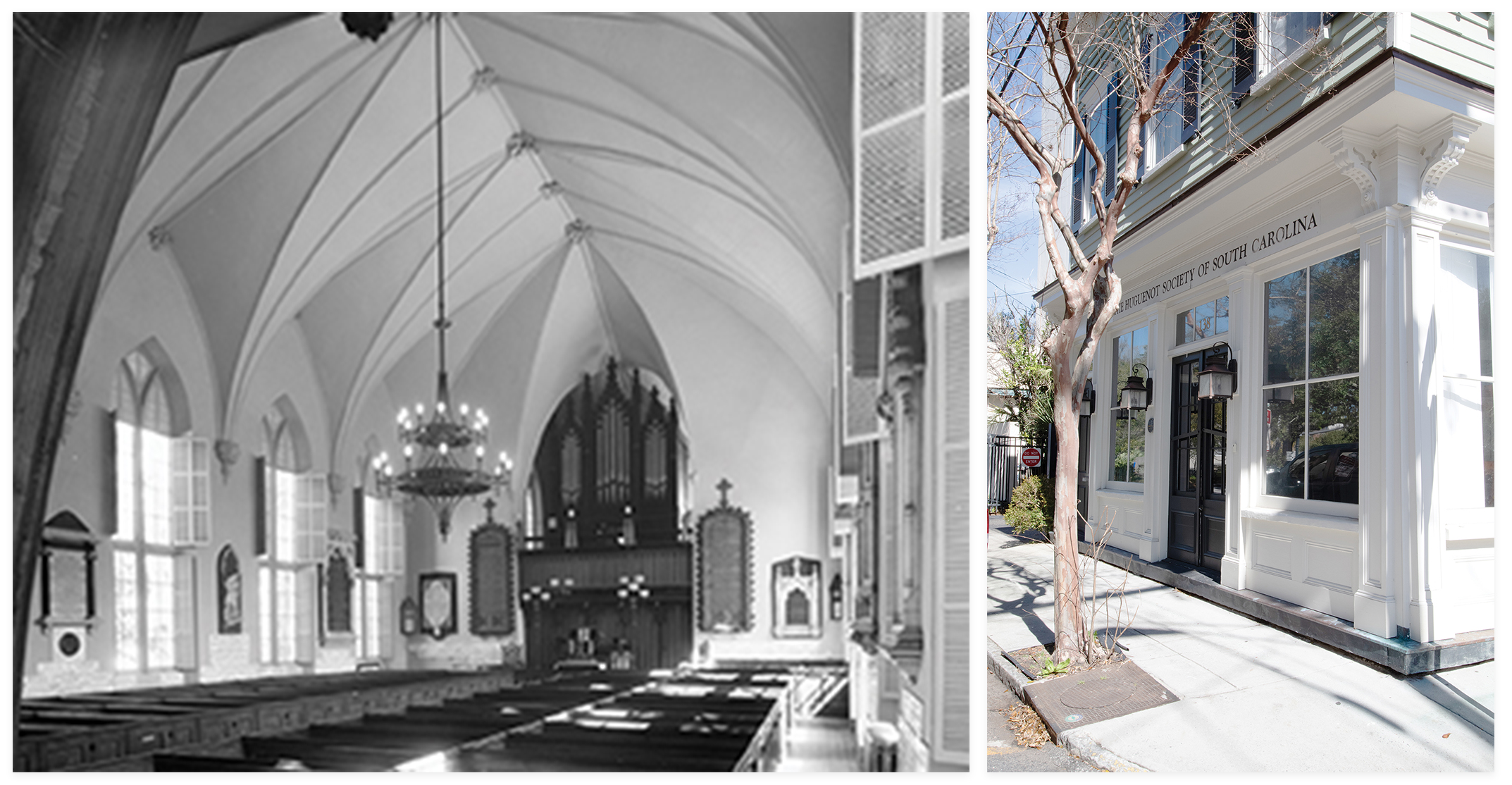

Huguenots built a church seven years after arriving in Charleston. Today’s building dates to 1844 (pictured here in 1904) and is full of memorials to Americans of Huguenot descent.

In April 1670, Carolina was founded, and the English settlement began. A decade later, the first group of Huguenots, between 40 and 50, arrived on the ship Richmond.

No list exists of who was on board—but the impact on the culture and history of the Lowcountry from those settlers and their descendants would be profound. Knowing the Huguenots would add much to the colony, the lords proprietors had printed circulars in French to tempt these Protestants living in exile away from inhospitable Catholic France to cross the ocean. They would be granted religious freedom and land, and Carolina, it was claimed, was perfect for planting olives, mulberries, and grapes so they could continue their traditions of producing olive oil, silk, and wine.

While those promises were unfulfilled, the new colonists flourished, founding a congregation the year they arrived and raising a church seven years later on the corner of Queen and Church streets. (The third on the site, dating from 1844, is full of memorials to Americans of Huguenot descent, among them George Washington. While the neighborhood is known as the French Quarter today, that designation is modern, coming into vogue in the 1980s).

(Left to right) Inside the Huguenots church in 1904; The Huguenot Society of South Carolina on Meeting Street.

Of the 2,500 or so Huguenots who came to North America, about 500 landed locally, but despite their numbers, intermarriage with the English majority led to cultural assimilation, and French, except in liturgy in Charleston, was heard less by the 1730s and ’40s. It was at about this time, too, that the French Benevolent Society, called the “Two-Bit Club” for amounts given for charity, opened its membership to others and became known as the South Carolina Society, still flourishing in its hall on Meeting Street. The Huguenot Society of South Carolina, dedicated to the preservation and study of Huguenot memory, opened in 1885.

Historical figures such as “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion; architect Gabriel Manigault; Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress; 19th-century US Attorney General Hugh Swinton Legare; 20th-century mayor, J. Palmer Gaillard, who began dismantling segregation in the city; and Porgy author DuBose Heyward are just a few of those Huguenot descendants who have added luster to their heritage and to Lowcountry history.