10 Flowers That Define Holy City Gardens

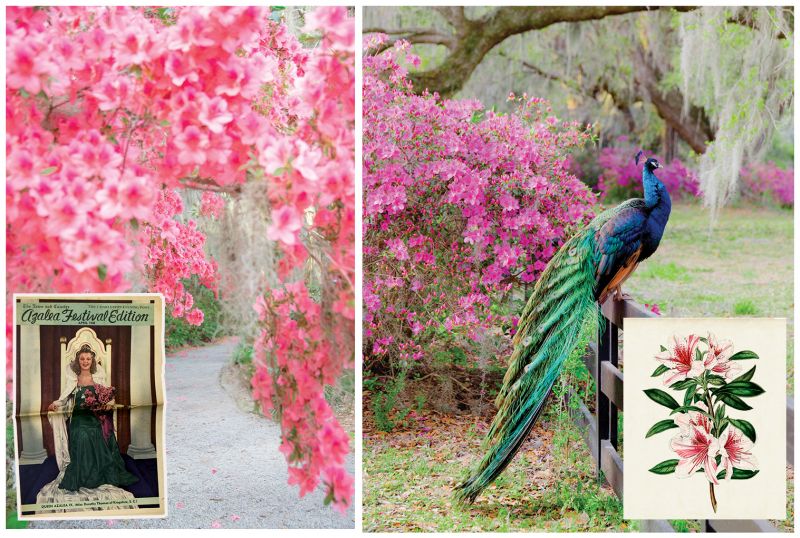

(Left) Azaleas bloom with abandon along the paths of Hampton Park. The City of Charleston launched the Azalea Festival in 1934, aiming to grow tourism and compete with New Orleans’ Mardis Gras. Amid parades, sports tournaments, air shows, and more, the headlining events were the Azalea Queen pageant—featuring competitors from across the state—and the Coronation Ball. (Right) With a little help from the roaming peacocks, hundreds of varieties of azaleas—including more than a dozen once thought to be extinct—turn Magnolia Plantation and Gardens Technicolor each spring.

Long before the first gardener sunk a shovel into Lowcountry earth, an extraordinary array of indigenous plants thrived, nurtured by the subtropical environment. Thus, an impressive stage was set for early, wealthy colonists, who in the 1700s began creating grand European-style gardens, built and tended by the people they enslaved. In the same century, several of the world’s finest naturalists moored in the port city, establishing vast experimental gardens, introducing plants from around the globe, and influentially networking with locals.

Over the years, Charlestonians dug in, cultivating ornamental gardens in even the smallest walled courtyards and prioritizing parklands. Landscape architect Loutrel Briggs arrived during the mid-1900s Charleston Renaissance and helped fortify the city’s canon of traditional plants—one that’s been carried into the 21st century with help from enduring groups like the Garden Club of Charleston. Here, we highlighted 10 quintessential local blooms, with peeks into each one’s history and essential info for growing them today.

Azalea (Azalea Indica)

As a self-prescribed cure for his own tuberculosis and for his Philadelphia-raised bride’s homesickness, Rev. John Grimké Drayton set out in the 1840s to enhance the gardens of his Magnolia Plantation home. He was inspired by the British movement toward informal “romantic gardens,” and azaleas were an early obsession; Drayton may have even introduced them to America.

The spring bloomers were a star attraction when the Draytons—facing financial ruin after the Civil War and the emancipation of their enslaved workforce—opened their gardens to the public in 1870.

Three decades later, a Lady Baltimore Magazine writer opined, “I have seen gardens, many gardens in England, France, and Italy.... But no horticulture that I have seen devised by Mortal man approaches the unearthly enchantment of the azaleas at Magnolia gardens.” Today, the site boasts the oldest collection of indica azaleas in the country.

Planted prolifically around homes and public spaces, the shrub was celebrated in Charleston’s weeklong Azalea Festival from 1934 to 1953. Summerville revived the tradition in 1972, centering the springtime Flowertown Festival around Azalea Park. This year, the enormously popular event has been postponed until October.

Origin: Japan

Hardiness zones: 5 to 9

Height: 2 to 6 feet, though some can grow much taller

Blooms: March and April

Conditions: Filtered sun; lightly acidic, loose, moist soil

Learn more fun facts about Azaleas here.

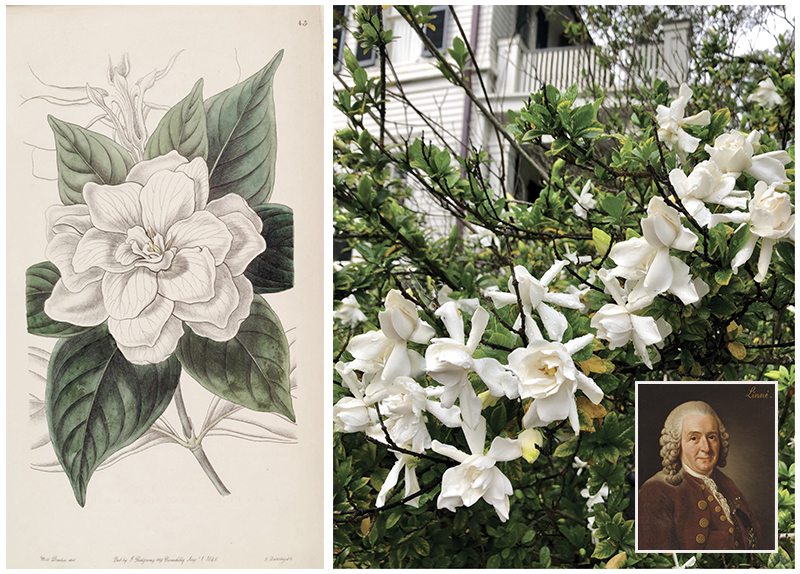

(Left) This hand-colored copperplate engraving—created by George Barclay from an illustration by Sarah Drake—appeared in an 1846 edition of Edwards’ Botanical Registe; (right) Homeowners often plant gardenias near piazzas, doors, and windows for utmost enjoyment of their alluring scent; (inset) Carl Linnaeus.

Gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides)

With a sweet scent masterful at conjuring summer memories, this treasured Southern blossom immortalizes a notable Charleston resident—but the reason may surprise you.

Raised in Scotland, Dr. Alexander Garden studied medicine as well as botany before accepting a job in the Holy City in 1752. Here, he began growing his medical practice, but also his knowledge and connections within the international botanical world.

He’d ultimately ship more specimens to Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus—who developed the binomial nomenclature system for classifying organisms—than anyone else in North America. Yet most of these were fish (some 41 species), lizards, and snakes.

So what of the shrub? When Garden believed he’d discovered new plants, he repeatedly asked Linnaeus to name them Ellisiana in honor of his friend John Ellis, a London zoologist. Ellis reciprocated and in 1760 convinced the Father of Taxonomy to name a resplendent, white-flowering plant Gardenia.

In a letter, Ellis promised to send Garden one of his namesakes, and America’s first gardenias may have grown in the teeming landscapes of his Broad Street house or Berkeley County estate. In any case, locals soon embraced the charmer, perfectly sized for petite downtown green spaces.

Origin: China and Japan

Hardiness zones: 8 to 11

Height: 3 to 8 feet

Blooms: From May into summer

Conditions: Light to partial shade and acidic, well-drained soil; regular water

Learn more fun facts about Gardenias here.

(Left) The fruit from many (but not all) loquat trees is tasty enough to use in jellies, pies, and cocktails. But given the beauty of spring’s orange clusters, plus aromatic fall flowers and leaves that stay luscious green all year, many residents award the plant garden real estate based on aesthetics alone; (far right) Fruits just beginning to ripen at the East Bay Street entrance to Lodge Alley.

Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica)

While the loquat tree doesn’t boast showy flowers—or linkage to big names in Charleston’s botanical history—it is a fundamental fruity layer of the Holy City landscape, with delicate white panicles in autumn foretelling spring’s edible orange gems.

And for that, we can thank 19th-century fruit scientist A. Pudgion. In an article posted to Facebook, Southern foodways historian Dr. David Shields wrote that loquats “became a garden fixture in Charleston in the 1850s and early ’60s when pomologist Pudgion sold hundreds of trees from his nursery....”

Like the other nine plants on our list, loquat trees were among the 40-some ornamental growers that renowned landscape architect Loutrel Briggs found best-suited to area gardens. He used these favorites in scores of private and public spaces from the 1920s into the 1970s, further solidifying each one’s position in the local canon.

Origin: China and Japan

Hardiness zones: 8 to 10

Height: 15 to 30 feet

Blooms: September to January

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; well-drained soil; regular water

(Left) French botanist André Michaux (pictured inset) brought the tea olive to North America via Charleston in the late 1700s. In fact, one of the inaugural shrubs could still be growing at Middleton Place, suggests Middleton Place Foundation president and CEO Tracey Todd, pointing to an incredible 40-foot-tall specimen. (Right) Sweetly scented branches reach over the Washington Square fence into Chalmers Street.

Tea Olive (Osmanthus fragrans)

This evergreen shrub—beloved for the intoxicating scent of its dainty white flowers—was introduced to the United States by French explorer and botanist André Michaux. Today, the Charleston International Airport’s Michaux Parkway honors the man who established an 111-acre botanical garden nearby in 1787, using it to grow plants he gathered from around the country.

By that time, Michaux had already roamed many parts of the globe, commissioned by King Louis XIV to collect plants and seeds that might prove valuable to his home country. In exchange, he brought America an array of exotic growers, including the tea olive.

The plant became a choice selection for Southern gardens during the antebellum period and has grown prolifically in Charleston ever since. Much of the year, it discretely forms hedges and offers backdrop to more vibrant blossoms. But then, it flowers.

Harlan Greene wrote in a 2014 Charleston essay: “Just when you’ve given up or forgotten its existence, it will ambush you with the sweetest smell imaginable...a faintly wistful smell, ripe apricots or something as unearthly as a ghostly harpsichord note or a happy memory.”

Origin: China, Japan, and The Himalayas

Hardiness zones: 7 to 11

Height: 10 to 20 feet

Blooms: Spring and fall

Conditions: Sun to partial shade; fertile, acidic, well-drained soil; regular water

Read Harlan Greene’s ode to the Tea Olive here.

At Boone Hall Plantation and Gardens (above), local rosarian Ruth Knopf (inset) planted an expansive collection of old roses, including Noisettes, that thrive in the Southern heat. (Right) French botanical artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté depicted a Noisette rose in his 1817-1824 tome, Les Roses. (Inset) ‘Champneys’ Pink Cluster’ was the first Noisette rose.

Noisette Rose (Rosa)

This storied clan of garden roses famously traces its lineage to Charleston. Accounts vary, but most begin with the rice planter John Champneys, who maintained an 11-acre garden on his Ravenel property. Around 1802, he created America’s first hybridized rose, crossing a musk and a China to yield ‘Champneys’ Pink Cluster’.

Champneys shared cuttings with his neighbor, French-born botanist Philippe Noisette, who continued to breed the stunner, creating the ‘Blush Noisette’, a fragrant climber with soft pink double blooms that appear throughout the year.

Noisette sold the new plants in the Southeast, while his brother, Louis, a Paris nurseryman, made them a sensation across the pond. Plant breeders continued to cultivate the rose, creating the class called Noisette.

Local Ruth Knopf is among the world’s leading Noisette rose experts and has helped drive efforts to bring it—and other antique roses—back to the city. Local green thumbs began planting new bushes in churchyards, historic house gardens, and city spaces to create The Heritage Rose Trail, completed in 2001. The trail—detailed in a brochure at chashortsoc.org—also showcases dedicated rose gardens in locales like Hampton Park and Boone Hall Plantation.

Origin: Charleston, South Carolina

Hardiness zones: Vary by variety

Height: Varies

Blooms: Spring and sporadically through summer and fall

Conditions: Full sun or light shade and regular water

From the 1840s to 1940s, Magnolia Plantation introduced some 150 cultivars of Camellia japonica to America; new propagation efforts have recently brought dozens of these to the on-site Gilliard Garden Center. Above are just a few blooms (and one sleepy frog) from the gardens’ 20,000 camellia plants. (Right) Looking toward the reflection pool at Middleton Place, which might be home to the oldest camellia plant in America. (Inset) Rev. John Grimké Drayton

Camellia (Camellia japonica & Camellia sasanqua)

Uncertainty surrounds the camellia’s American debut, but there’s a good chance André Michaux was responsible and that he, in fact, brought some of the country’s very first camellias to Middleton Place in 1786.

The latter claim has been passed down through Middleton family oral history, but in recent years, the Middleton Foundation has unearthed increasing evidence to support it. For example, Governor Henry Middleton signed a 1788 copy of Thomas Walter’s Flora Caroliniana and added, “This was Michaux’s copy.” And by 1814, Charles Drayton of the neighboring Drayton Hall was writing in his diary about taking cuttings from camellias at Middleton Place.

The historical gardens now boast 10,000-plus camellias, including many that are more than 200 years old, planted and cared for by people enslaved by the Middletons. Among them is the towering Reine des Fleurs (Queen of Flowers), believed to be one of four camellias that Michaux gave the family—probably in thanks for being allowed to collect plants from the property.

Just up the road at Magnolia Plantation, Rev. John Grimké Drayton also went wild for camellias. He began propagating the shrub in the mid 1800s, creating the largest camellia collection in America before the Civil War.

Origin: China

Hardiness zones: 6 to 10

Height: 8 to 12 feet

Blooms: Sasanquas peak in November and December, with japonicas following from January into March.

Conditions: Partial sun in well-drained, moist, acidic soil

Learn more fun facts about Camellias here.

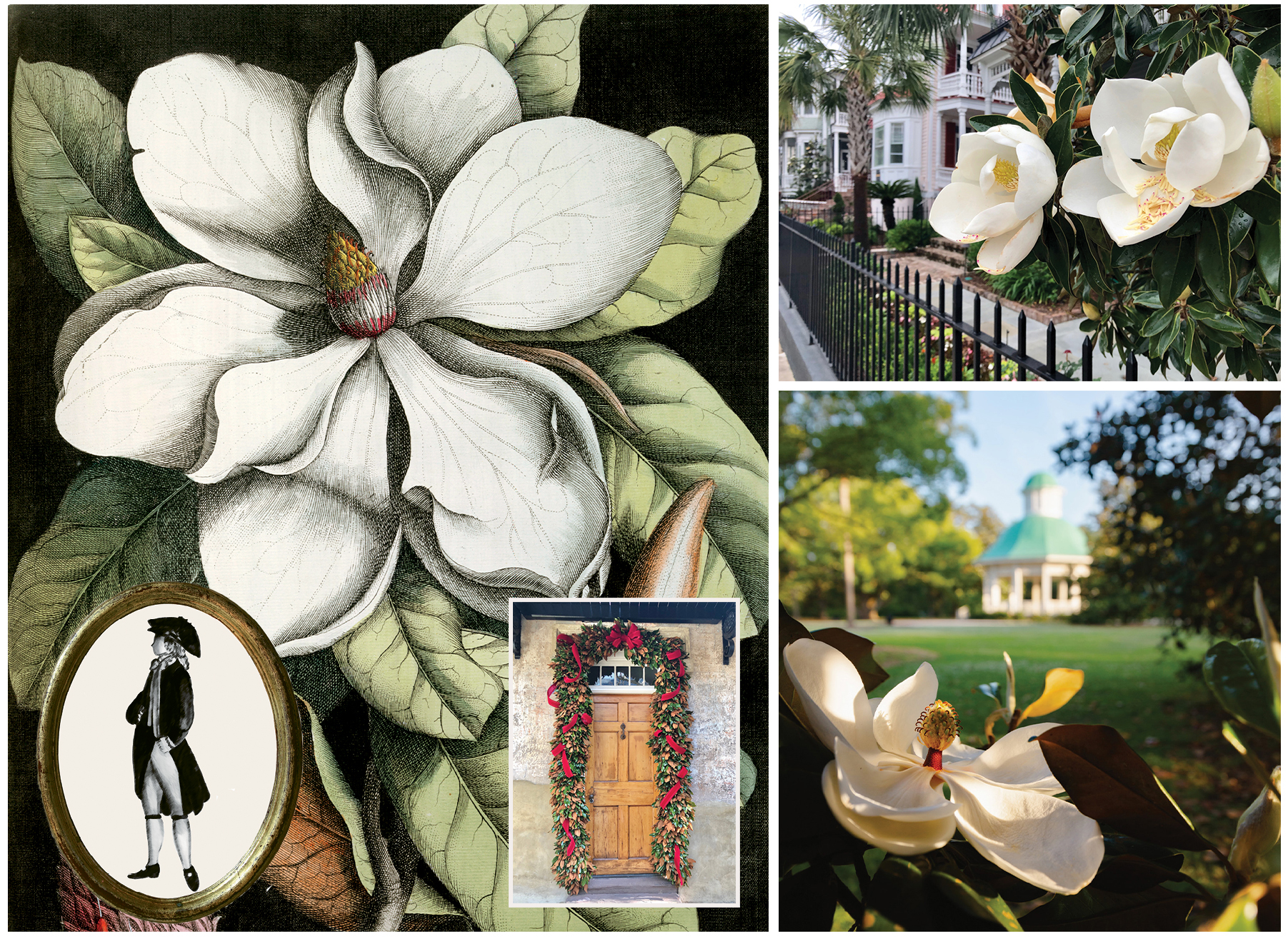

Mark Catesby’s 1729-1747 (inset, above left) tome The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands featured Georg Dionysius Ehret’s famous etching, Magnolia grandiflora (The Laurel Tree of Carolina). (Inset above right) A lush magnolia leaf garland trims a downtown doorway for the holidays. (Right) Eighteenth-century Charleston naturalist Dr. Alexander Garden called the magnolia—seen above at Hampton Park—“the finest and most superb evergreen tree that the earth produced.”

Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora)

With fragrant flowers the size of dinner plates, seed pods jeweled in ruby berries, and colossal leaves—glossy green on top and velvety brown on bottom—the indigenous Southern magnolia is “grand” indeed.

British explorer Mark Catesby must have spied the magnificent tree promptly upon landing in Charleston in 1722. He used the port city as home base while roving the state’s wilderness, collecting and sketching the flora and fauna he discovered. He’d spend the next two decades recording his findings for The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands—the first fully illustrated study of plants and animals in North America. Interestingly, the plant he called “The Laurel tree of Carolina” is one of only a few that Catesby did not personally depict: Georg Dionysius Ehret is responsible for the book’s now-famous magnolia blossom engraving.

Charleston residents were duly besotted with the native knockout: By the mid 1800s, Rev. John Grimké Drayton was calling his 1676 estate Magnolia-on-the-Ashley for a grove of the trees that led to the river. Town dwellers also cultivated the magnolia, and locals have long used its leaves in holiday garlands and wreaths, entrenching it in the city’s decorative traditions.

Origin: Southeastern United States

Hardiness zones: 6 to 10

Height: 60 to 90 feet

Blooms: May and June

Conditions: Full sun to partial shade; rich, loamy, acidic soil; regular water

Learn more fun facts about Magnolias here.

The first Lady Banks rose was probably white, like the one that climbs a post at 47 Meeting Street (inset above). Today, you’re more likely to see the scentless yellow ‘Lutea’, shown above at South Battery’s Harth-Middleton House. (Right) Seen here at the corner of King and South Battery, the double white flowers of Lady Banks ‘Alba Plena’ smell faintly of violets.

Lady Banks Rose (Rosa banksiae)

Historical details about this rose’s earliest years in the Lowcountry are scarce. However, it is known to have arrived in England in 1807, plucked from China by William Kerr, who served as a plant hunter for Sir Joseph Banks, director of London’s Kew Gardens.

A March 1947 Charleston Evening Post article on rose gardening reported, “Rosa banksiae (Lady banksiae) has been in the South since 1860, when it was brought from Macon, Georgia.”

Holy City gardeners certainly fell for the vigorous climber that in early spring is positively covered with clusters of petite yellow or white flowers (depending on the cultivar) with near-thornless stems. Frequently given a starring role in historic gardens, Lady Banks roses can be found climbing arbors, spilling over old brick walls, and espaliered against dependency buildings.

Origin: China

Hardiness zones: 9 to 11 evergreen; 6 to 8 deciduous

Height: 20 feet or more

Blooms: March and April

Conditions: Full sun, well-draining soil, regular water

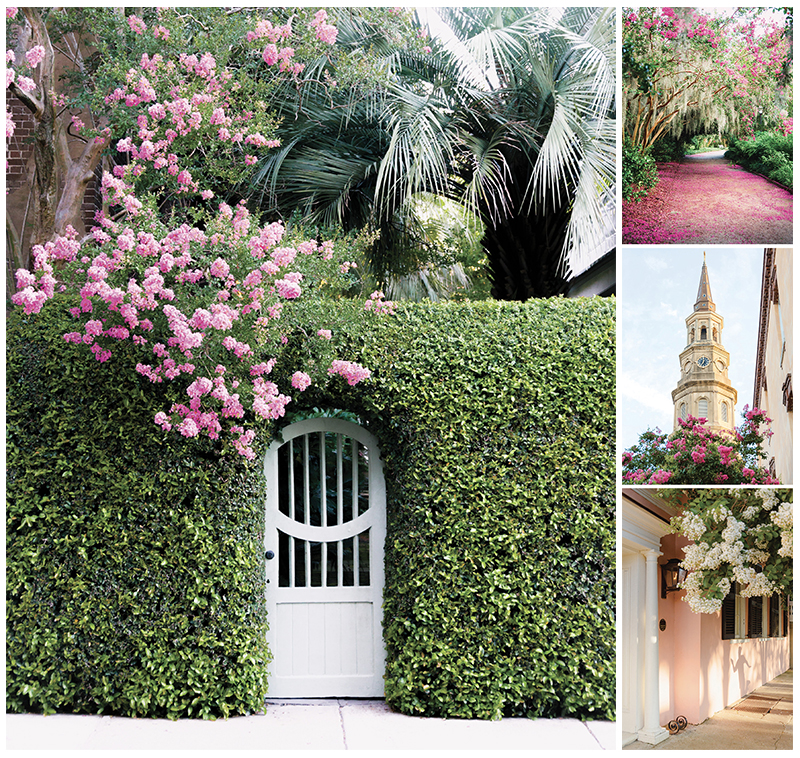

(Left) A fig vine-covered wall at 70 Tradd Street lends a lush backdrop to hot-pink blossoms. (Right, top to bottom) Crepe myrtle confetti litters a Hampton Park pathway; views of St. Philip’s are never finer than when the trees bloom along Church Street; each summer, creamy white flowers offset 47 East Bay Street’s shell-pink exterior.

Crepe Myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica)

Summer’s brightest-blooming tree was another gift from André Michaux, making its United States premiere right here in Charleston in 1790. With silvery smooth bark and flowers that freshen the most dogged days, the import soon took its place along city streets and in gardens all over town.

Writing on the benefits of crepe myrtles in a July 1945 Charleston News and Courier article (alongside news of World War II’s final months), Walterboro historian and photographer Beulah Glover gave insight into the tree’s intimate position in local landscapes. “It seems, somehow, to represent a home,” she wrote, “and when one wanders through overgrown woodland paths, where all sign of life has gone and there finds a group of crepe myrtle, instinctively one knows that on this spot once stood a home.”

Origin: China and Korea

Hardiness zones: 6 to 9

Height: Up to 20 feet, depending on variety

Blooms: July and August

Conditions: Full sun, fertile soil, and moderate water

Read an ode to blooming crepe myrtles here.

A perfect match to East Bay’s Primrose House, Carolina jessamine can also be found scrambling through trees in Lowcountry woodlands.

Carolina Jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens)

On February 1, 1924, South Carolina lawmakers adopted Carolina jessamine as the official state flower. Inspired to poetics, they explained: “It is indigenous to every nook and corner of the State; it is the first premonitor of coming Spring; its fragrance greets us first in the woodland and its delicate flower suggests the pureness of gold….”

The blooms may be delicate, but tumbling together, they create a dramatic cascade—one that captured the attention of Mark Catesby during his 1720s exploration of the region. He showcased the vine in The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, dubbing it “yellow jessamy.”

Several decades later, André Michaux deemed jessamine seeds valuable enough to send home to France along with the likes of loblolly pine and Spanish bayonet. By then, Charleston residents had surely brought the showy evergreen in from the wild, using it to shade arbors, climb trellises, and soften the brick walls enclosing town gardens.

Origin: Southeastern United States

Hardiness zones: 6 to 9

Height: 20 feet or more

Blooms: February and March

Conditions: Full to partial sun; rich, well-draining soil; regular water

Learn more fun facts about Carolina jessamine here.

Flower Finder

These historical gardens are lush with Charleston’s signature blooms

Cypress Gardens

Paths and boardwalks wind through a scenic swamp and informal gardens dating to the 1920s. 3030 Cypress Gardens Rd., Moncks Corner. Daily, 9 a.m.-5 p.m. $10-$5; free for child under six. cypressgardens.berkeleycountysc.gov

Hampton Park

More than 60 ever-blooming acres comprise the city park system’s storied crown jewel. 30 Mary Murray Dr. Sunrise-sunset. Free. charlestonparksconservancy.org

Heyward-Washington House & Joseph Manigault House Gardens

Since the 1940s, the Garden Club of Charleston has maintained the period gardens at these historic homes. Heyward-Washington House, 87 Church St. & Joseph Manigault House, 350 Meeting St. Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. & Sunday, noon-5 p.m. $12-$5; free for child under three. (843) 722-2996, charlestonmuseum.org

Magnolia Plantation & Gardens

The oldest public gardens in America are especially renowned for their camellia and azalea collections. 3550 Ashley River Rd. Daily, 9:30 a.m.-5:30 p.m. $20-$10; free for child under six. (843) 571-1266, magnoliaplantation.com

Middleton Place

Formality reigns at the country’s oldest landscaped gardens, which trace their roots to 1741. 4300 Ashley River Rd. Daily, 9 a.m.-5 p.m. $26-$10; free for child under six. (843) 556-6020, middletonplace.org

Nathaniel Russell House Museum

Plants traditionally used in the 19th century fill the formal gardens around the 1808 Federal townhouse. 51 Meeting St. Thursday-Sunday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. $12-$5; free for child under six. (843) 724-8481, historiccharleston.org

Photographs by Kim Graham; (camellias) Melinda Smith Monk; Courtesy of (Van Houtt’s azalea indica) Jim Cothran; Charleston County Public Library; Carl Linnaeus portrait by Alexander Roslin; illustration from Edwards's botanical register Wikipedia; Sebastiano Secondi; Botanical illustration by William Hooker courtesy The Charleston Library Society; courtesy of (Daguerreotype of François André Michaux from the Harvard University Library) Wikipedia; Images by (Ruth Knopf) Chris Smith & courtesy of (wall) Boone Hall Plantation & (Redouté’s noisette rose) Audubon Gallery; (Reine des Fleurs) Erica Navarro, Piper Monk & courtesy of (botanical drawing by Abbe Laurent Berlese) Audubon Gallery & (John Grimke Drayton) Loc.gov; Images by (Catesby illustration) Jülide Dengal, (South of Broad Magnolia & Garland) Melinda Smith Monk, & (Hampton Park Magnolia) Kim Graham & courtesy of (Magnolia Grandiflora, by Georg Dionysius Ehret) Octavoi Corp. & the California Academy of Science; Napat