Before soft drinks and seltzer water were omnipresent in supermarkets, Lewis Y. Chupein II’s 19th-century soda fountain was the place to go for the fizzy stuff

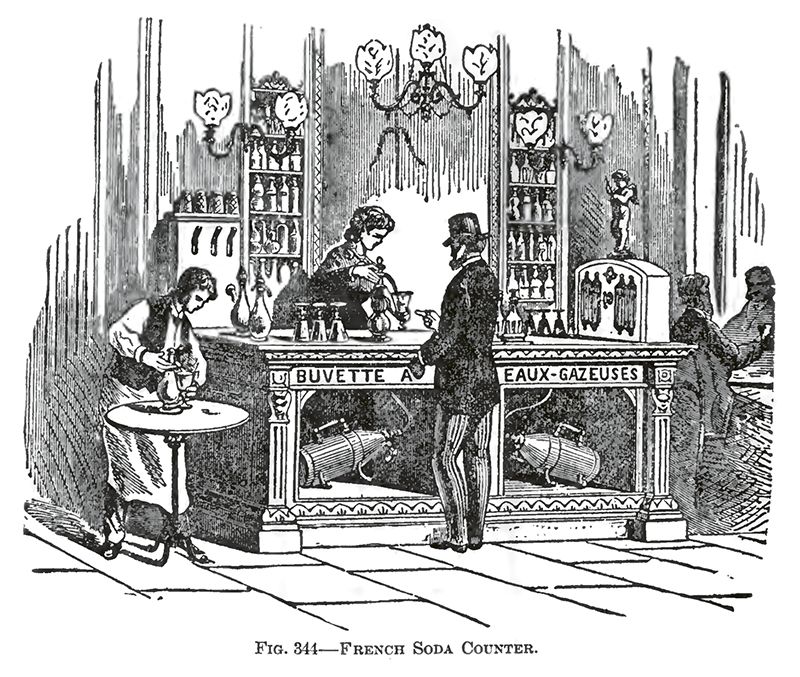

PHOTO: Fountain Views: Lewis Y. Chupein II’s soda fountain closely resembled the ones in France in the mid-1800s.

Born in Charleston in 1802, Lewis Y. Chupein II spent most of his boyhood days at his father’s businesses on Broad Street. A French hairdresser who came to the States during the French Revolution, his father first opened a fancy goods store at 137 Broad containing millinery, lingerie, perfumes, cosmetics, and luggage. Then in 1823, the elder Chupein set up a high-end hair salon at 13 Broad that was equipped with a “mineral water fountain” (as it was described in 1824 by the City Gazette) serving carbonated spring water with pineapple, lemon, and strawberry flavorings. Lewis, then 21, superintended the fountain under his father.

At the time, artificially bubbling water (as opposed to the naturally sparkling spring water found in 18th-century spas in Saratoga, New York, and western parts of Virginia) was still something of a novelty. In 1767, chemist Joseph Priestly had discovered a method of carbonating water artificially while experimenting at a brewery in Leeds, England. Soon, Americans approximated the effervescence of spa spring water, creating soda water. It was just a matter of time before confectioners began infusing it with fruit-flavored syrups, producing a more agreeable product than the sulphurous fluid that bubbled from the ground.

Young Lewis learned the trade, and soon Charleston was refreshed with his sprightly soda water tonics. On May 1, 1828, he took over the business at 13 Broad, rebranding it as a soda fountain and ice cream parlor (the sherbet flavors alone included raspberry, strawberry, lemon, orange, apple, peach, apricot, and nectarine). With refrigeration and flavored syrups, he gave his carbonated mineral waters a bracing fizz and surprising taste. In 1830, he added iced lemonade and ginger beer to the menu.

Lewis’s soda fountain was a seasonal operation, opening on May 1 and shutting on October 1. During the off months, he traveled to secure ingredients and equipment, learn new processes, and scout the newest décor in refreshment parlors. His was a fashionable enterprise, requiring acute attention to the latest trends in the business. One of the shifts in taste Lewis noticed in his travels was the increasing body of persons abstaining from alcohol (the American Temperance Society organized in 1826) and the consequent growing popularity of soft drinks—precursors to today’s mocktails. In the spring of 1832, he advertised in Charleston Courier, “Whiskey, Brandy and Rum / Madeira, and even Champaigne— / The season of Soda and Sherbet is come, / And our fountains are flowing again: / our Soda or Nectar is better / By far than all Liquors combined; / And one drink will prove to a letter, / That there’s few but are of the same mind [sic].”

Charleston’s pioneer of the soda fountain went on to introduce to the city more tonic flavors and sweet treats for a quarter of a century. Before Lewis passed away in 1853, his store at 13 Broad was renowned for fashionable gossip, refreshing beverages, and the absence of drunken bluster—a downtown destination for both sexes at a time when those were hard to come by.

Image from A Treatise on Beverages by Charles Herman Sulz