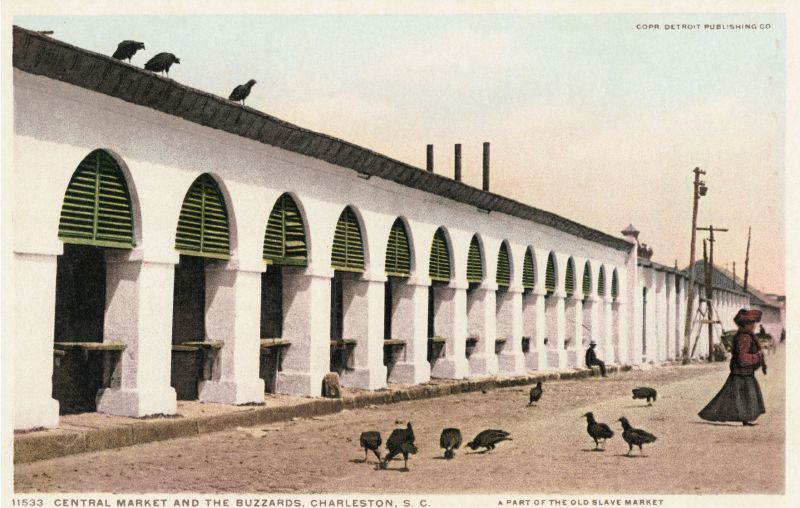

Some called them “vultures,” others “turkey buzzards,” “carrion crows,” or “Charleston eagles.” For decades, they symbolized Old Charleston—imperious, jealous, and entirely fearless as they congregated around the butcher stalls on Market Street. In the era before in-ground sewers and civic incinerators, they constituted the sanitation department. Whatever was discarded by the butchers—bone, gristle, fat, or skin—provoked a tussle. Then, voilà, it was gone. No other city possessed so tame, so tolerated, so sober-looking an assembly of carrion birds. Tourists asked to see them. A stroll about town did not produce satisfaction until the iconic creatures had been inspected.

The buzzards dominated the Market district for a century, appearing shortly after the “Centre Market” opened in 1809. When the Duke of Saxe-Weiner-Eisenach visited in 1825, he noted the throng of them roosting on the brick Market house and adjoining buildings and marveled how they kept the streets and floors spotless. He added, “There is a fine of five dollars for the killing of one of these birds” because they were regarded “as very useful animals.” The fine was raised to $10 in the 1880s.

There’s nothing attractive about the animal; its appearance is, in fact, rather distressing. In 1888, New York columnist Bill Nye addressed the problem: “His face is as plain as the clear-cut mouth and retreating forehead of the catfish. He has a raw-looking head and neck, and he is willing to eat things which even the boarder at a second-class hotel would disdain to enjoy.”

Furthermore, the bird had neither a melodious nor sublimely terrifying song. Instead, it hissed. Its foul breath would shock those who caught whiff of it for the first time. When still, the creature seemed “grave and solemn;” when in motion, it hopped awkwardly and was given to raising and stretching wings at quaint angles. “Ungainly” was a term used to describe its locomotion when not flying.

And yet, with the perverse pride that Charlestonians have long cultivated, the birds were celebrated as the gloomy genius loci of the old city. When semi-pro baseball came to Charleston at the end of the 19th century, the local team was named the Charleston Buzzards.

So when did these famous creatures lift from the cobbles, never to alight again on the Market roof? I will propose a date: June 1918.

Trouble began in 1909, when certain of the state’s big hog farmers started to suspect that the spread of hog cholera was due to turkey buzzards eating diseased meat and then flying to other locations. For nine years, the pork interest in the state waged a campaign, finding vocal veterinarians and health officials to endorse their charges.

They claimed that the health and security of the population lay in peril, and that instead of serving as “assistant members of the local board of health,” buzzards were a pox upon the land. At the time, there were scientists who argued against this belief. Dr. E. W. Nelson of the USDA, for instance, declared that a “violent campaign has been waged against buzzards and crows, especially in farm journals in South states;” the case against the birds, he believed, “has been very much overstated.” (In fact, tests later proved that the buzzard’s digestive system killed the bacteria. The true vector for the disease? Humans.)

Regardless, the Charleston Chamber of Commerce bought into the panic and sponsored a bill permitting the killing of the buzzards, overthrowing the legal protections and fines that had existed in the city for a century. It passed, and bounties were offered for creatures killed.

Still, legally condoning the termination of buzzards did not prompt Charlestonians to seize their double-gauge shotguns and head to the Market. Six months after the passage of the buzzard law, a reporter observed, “Nobody seems to be taking advantage of the ‘anti-buzzard law’ to massacre the buzzards. This seems to be another matter as to which the public is wiser than those who make its laws for it.”

No, it was another regulation that did in the Charleston eagles. In an effort to ensure sanitary fare for U.S. troops in Charleston during World War I, the U.S. Public Health Service imposed prohibitions against the open-air disposal of meat. Screens had to protect all displays. In an instant, the protein source that had drawn generations of buzzards to Market Street was shut off. Charleston City Council appointed a food inspector in July of 1918 to police the restaurants and markets in a campaign against “unsanitary conditions.” The old assistants to the board of health—the eagles—were demoted and deprived of sustenance.

Without the state officials and sanitation officers omnipresent during the war, the buzzards may have stood a chance. They might have dined at the city dump, but the city was cajoled into building a state-of-the-art incinerator. Local witnesses knew what was going on—indeed one wrote to The State newspaper in Columbia: “One of the Charleston ‘institutions’ that will feel greatly the effect of the ‘swill furnace’ is the time-honored and widely known buzzard, which now feasts at the garbage dumps with relish. First the buzzard deserted the central market when the butchers had to put in screens and stop throwing meat scraps into the street, and now the dump pile will soon lose its daily contribution and this means further restrictions of B’rer Buzzard’s opportunities for good living.”

The butchers were all screened by April 1918. The incinerator went on line in June. That summer the Charleston eagles bid adieu, never to congregate in the heart of the city again.

Image reprinted with permission from Charleston, 1900-1915, by Raymond K. Benton Jr. Available from the publisher online at arcadiapublishing.com or by calling 888-313-2665