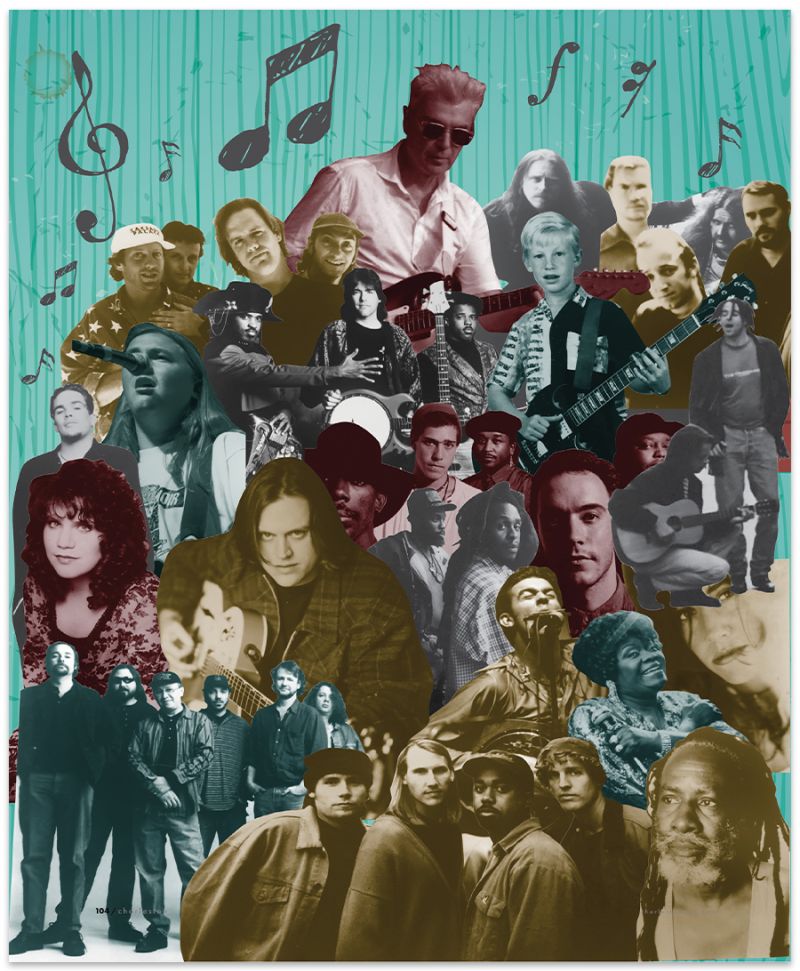

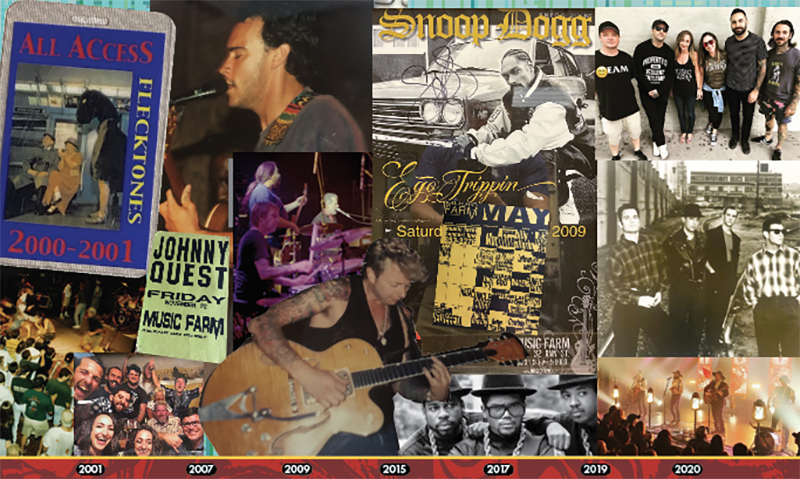

Revisit the Farm’s beginnings as a renegade club, the countless bands who struck a chord there, and many rocking good memories

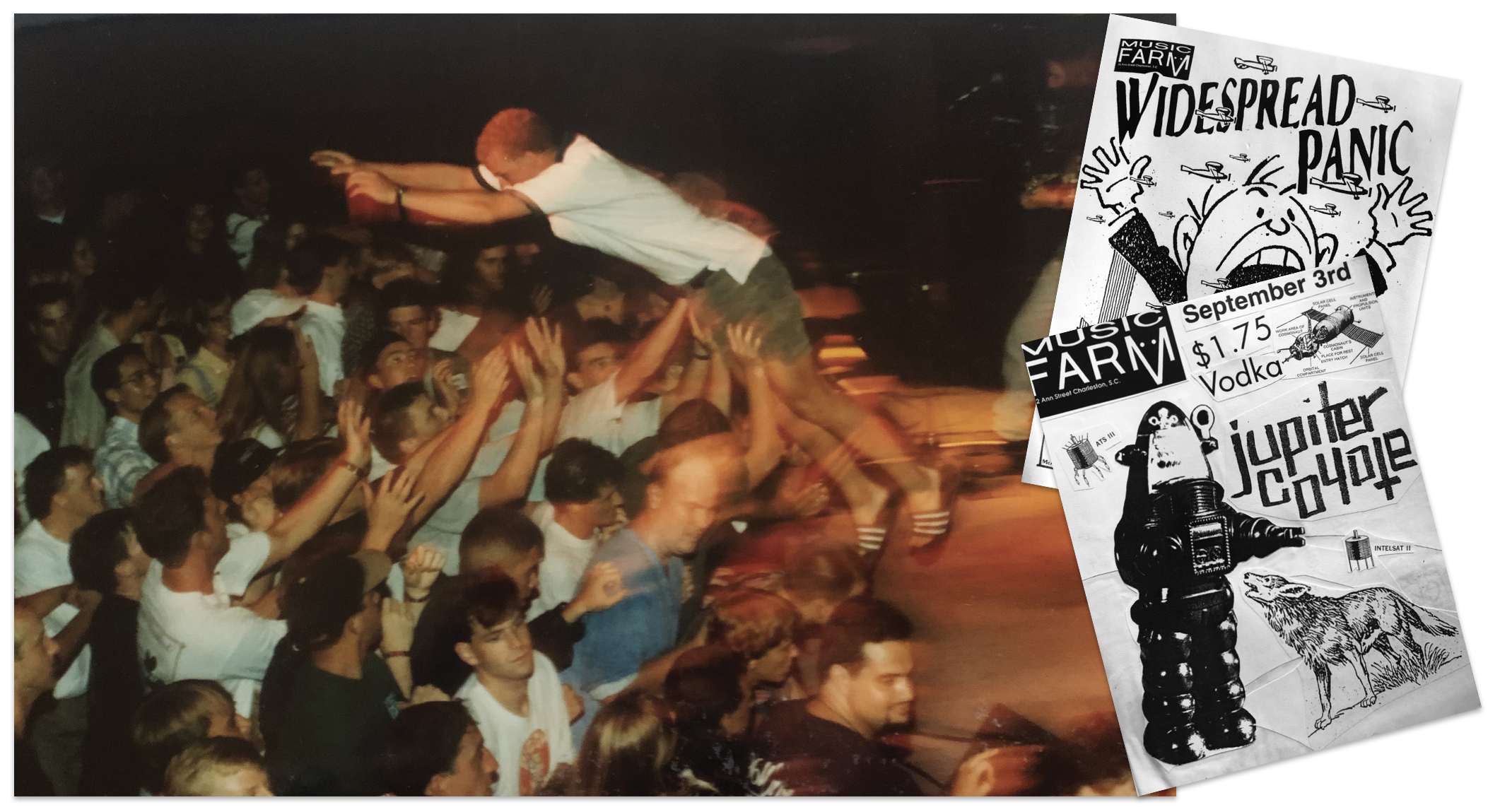

On a warm Friday afternoon last October, Kevin Wadley stood on the dance floor of the Music Farm, searching for a hole in the floor. When he found it—a circular crack in the sticky, black surface—he pushed his toes into the depression, causing white dust to spit into the air. “This is from a portable basketball goal we used to wheel in,” says Wadley, the venue’s co-founder, recounting stories of shooting hoops before sound check with acoustic jam rockers Jupiter Coyote in the 1990s.

Across the room, Charles Carmody discovered a cavity in a brick wall and daringly put his hand in to pull out a string of silver tinsel. He reached back in and pulled three more sparkling, lengthy pieces from the hole, where they’ve been stuffed for who knows how many years.

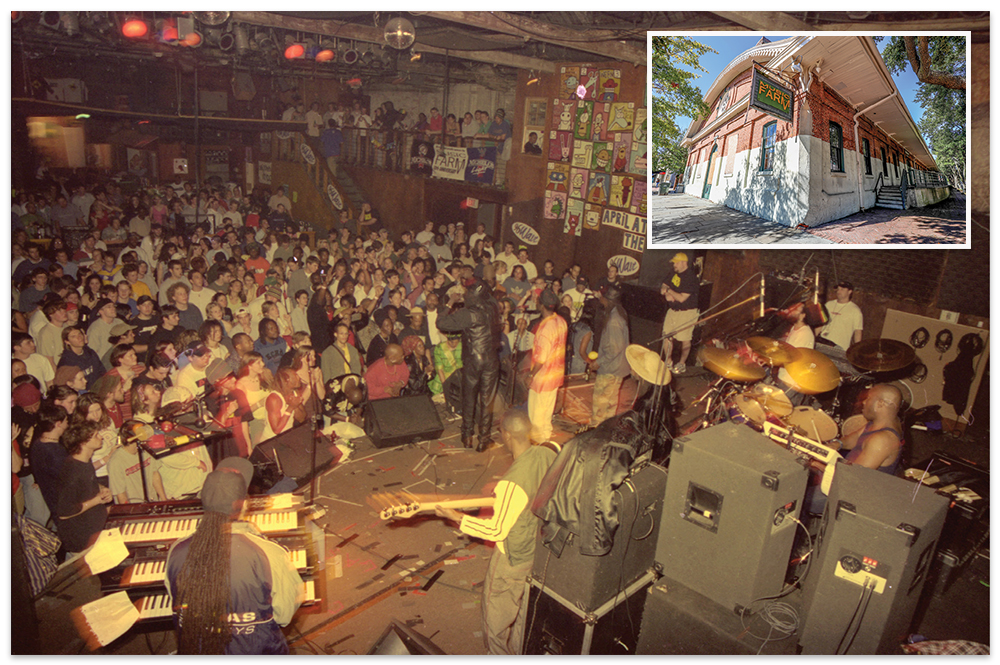

Next month, Carmody and his team from the Charleston Music Hall will debut a renovated, rebranded, and reimagined Music Farm. Although the Farm changed hands multiple times (and location, once) between its 1991 opening and unexpected—but threateningly permanent—closing at the start of the pandemic in March 2020, each new owner largely left the interior intact. The bar, the bathrooms, and the walk-in coolers all look much like they did in the ’90s when bands like Widespread Panic and The Connells were regulars in the venue.

Listen to Music Farm favorites on the Spotify playlist below:

The building is a former rail yard used to repair trains. But for longtime patrons, the allure of the soaring ceilings, brick walls, and distinctive ironwork windows was overshadowed by the inconvenience of getting a drink or reaching the bathroom through the crowd, compounded by speaker placement that often sounded like hearing a band play in a tunnel. By the 2010s, national acts like Old Crow Medicine Show and Michael Franti still filled the 960-person capacity venue, but loyalties (or affinities, even) didn’t extend to the space, despite its historic charm.

Improvements around each of those pain points are central to the plan for the new Farm. Carmody and his team will run both the Music Hall and Farm via Frank Productions, a Madison, Wisconsin-based promoter within the Live Nation umbrella.

The arrangement allows for local management by former patrons. Carmody fondly remembers seeing musicians like Andrew Bird and Donavon Frankenreiter at the Farm as a teenager, returning home with an under-21 “X” in permanent ink on his hand and second-hand cigarette smoke permeating his clothes. Carmody’s guidance, along with the reach of Frank Productions’ national bookings, helps ensure that the Farm’s historic appeal gets the respect it deserves, while opening the door to a new generation of “I can’t believe I was there!” memories at the Ann Street venue.

Back in 1991, Kevin Wadley was a gigging guitarist in The Archetypes, a Charleston rock band drawing influence from the alt-rock Athens, Georgia, scene up the road. Driving down East Bay Street one evening, Wadley spotted a party at the shuttered Tremors nightclub. He pulled in and discovered that Mongo Nicholl—the founder of the Upwith Herald (later the Charleston City Paper)—was hosting a concert in the otherwise-closed club. Inspiration struck. Wadley rented the room and booked Uncle Mingo, another ’90s Lowcountry alt-rock powerhouse. “They killed it,” Wadley recalls of the show. “I did that a few times and then said to myself, ‘I can start a nightclub.’”

Wadley pitched the concept to his friend Woody Bartlett, part owner of radio station 96 Wave. Although the station proved to be a huge supporter of the Farm throughout the ’90s, Bartlett worried about conflict of interest as a station owner, instead connecting Wadley with 96 Wave promotions director Carter McMillan, to whom Wadley presented a thorough business plan. “He’d put a lot of thought into it,” McMillan notes. “I looked at it and said, ‘If I read that thing, I probably won’t do it.’ If there were doubts, we knew we’d overcome them because we felt so strongly about the music.”

Riffing on a name over dinner at Pinckney Cafe, they wanted to convey the idea of partying in the country. (In those days, East Bay north of Market Street felt remote.) The pair opened the first Music Farm in the Tremors location at 525 East Bay Street. As a musician, Wadley emphasized sound—a good PA and quality monitor mix—and drinks were $1.25. “We took care of the bands,” he says. “As a musician, I knew how I wanted to be treated, and that paid off for us.”

The Farm was a hit. Local bands had a big stage to build their audience, punk kids had a place to mosh to acts like Social Distortion, and the F&B crowd had a late night hangout—the “Disco Hell” dance party ran on weekend nights from 1:30 to 5 a.m. Downtown’s Myskyns Tavern closed during the same era, and the only other comparably sized venue was The Windjammer on Isle of Palms. Wadley and McMillan quickly needed to expand from their 500-person space.

Dub In The Club: In the mid ’90s, Jamaican roots reggae group, Culture, drew a full house; (Inset) Center Stage: Before the pandemic, lines of eager concert patrons would wrap around the building to Ann Street.

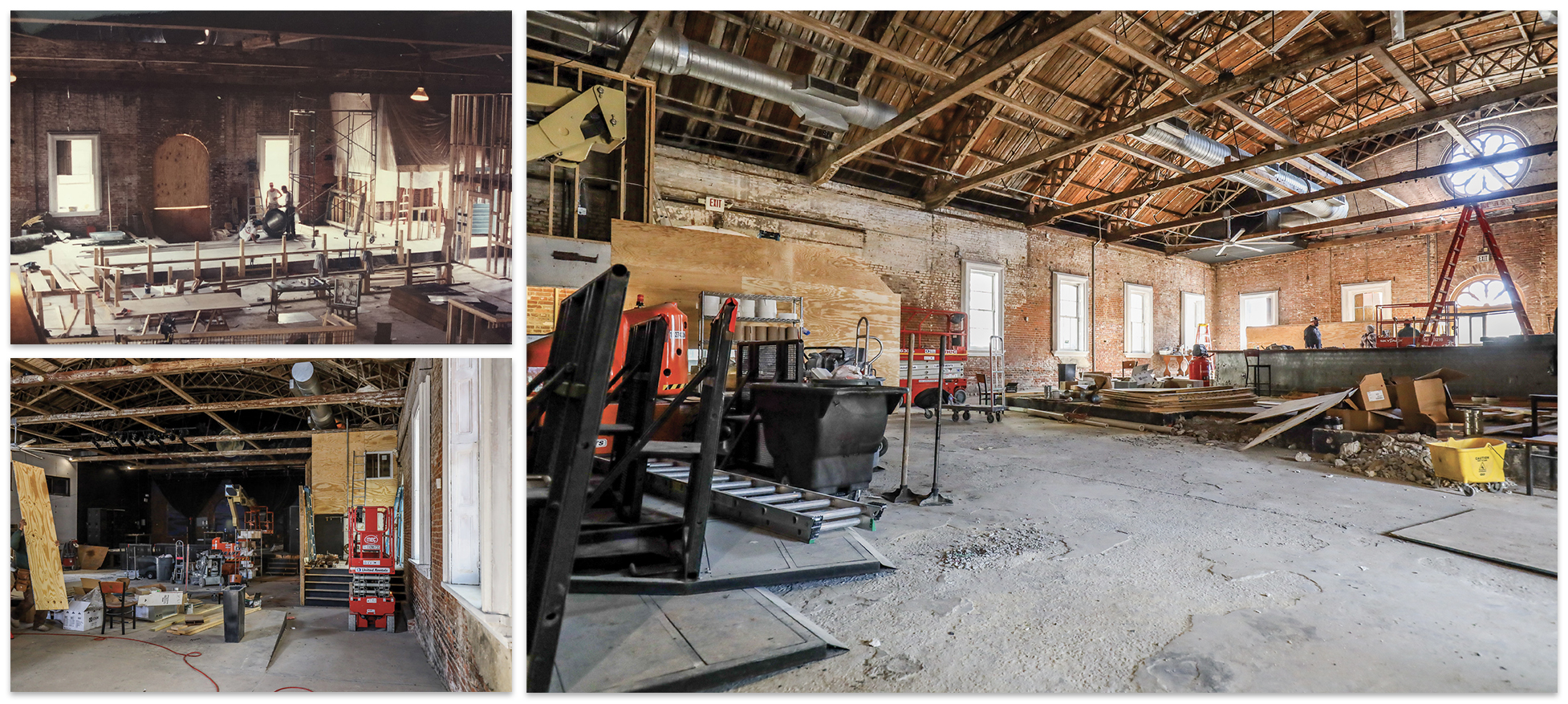

When Wadley and McMillan first walked into today’s Music Farm in early 1993, the floors were dirt and the last occupants had been railroad mechanics. To renovate and grow the business, they took on partners, including Jed Drew, publisher of Charleston magazine, and the building’s current owners, Jerry Scheer and Mark Cumins of Homegrown Hospitality Group (TBonz, Pearlz, Kaminsky’s). “We thought it would be fun to try for a while,” says Scheer of the original investment. “Little did we know that 30 years later, we’d still be a viable part of the music scene.”

Graphic designer Gil Shuler created the club’s original posters, and architect Reggie Gibson led the redesign, including the bar and stage as they stand today (the original purple and yellow floors soon faded). After a $700,000 remodel, the Music Farm reopened in August 1993 with the funk band Ohio Players. Soon, touring groups that had once overlooked Charleston—Dave Matthews Band, Stray Cats, The Grapes, Warren Zevon—made the Music Farm a regular stop. “Going to 1,000 people took us to the next level with booking agents,” Wadley recalls. “We were open seven nights a week.”

Wadley also remembers mopping up after heavy metal band GWAR sprayed the room with fake blood and punk group the Dwarves mashed pimiento cheese into the electrical breaker box. An all-ages bill featuring the Offspring, Rancid, The Queers, and Elvis Hitler was paused when a preteen tried to stage dive and wound up being carted out in an ambulance. “Later that week, I’m in my office and this kid knocks on the door,” says Wadley. “He said, ‘Hey man, I fell off the stage and missed the show. Can I get my $12 back?’”

The venue also helped to build local bands like Jump, Little Children (JLC) into national acts. “To say that the Music Farm formed us as a band is an understatement,” says JLC cellist Ward Williams, recalling the band’s theme nights when they performed at the Farm every Tuesday during the summer of ’95. “I definitely remember the high point—Wizard of Oz night—and the low—cafeteria night, where we lazily chucked tater tots into the crowd.”

In those pre-cell phone days, Wadley and McMillan took shifts at the Farm’s office all day long, ensuring someone was always there to answer if an agent called about bringing their band to town. That dedication helped the Farm to draw touring groups that might have otherwise passed Charleston by. But between the long days and late nights, the years took their toll. “I was cooked,” says Wadley of his decision to close. “I needed a break.”

Seven years of balancing close calls with laughs and musical moments were stressful and tiring. The music scene was also changing. Myrtle Beach’s House of Blues was competing for bookings, and 96 Wave was sold, taking away the Farm’s best source of radio marketing. To remain vibrant and profitable, the Farm needed fresh energy.

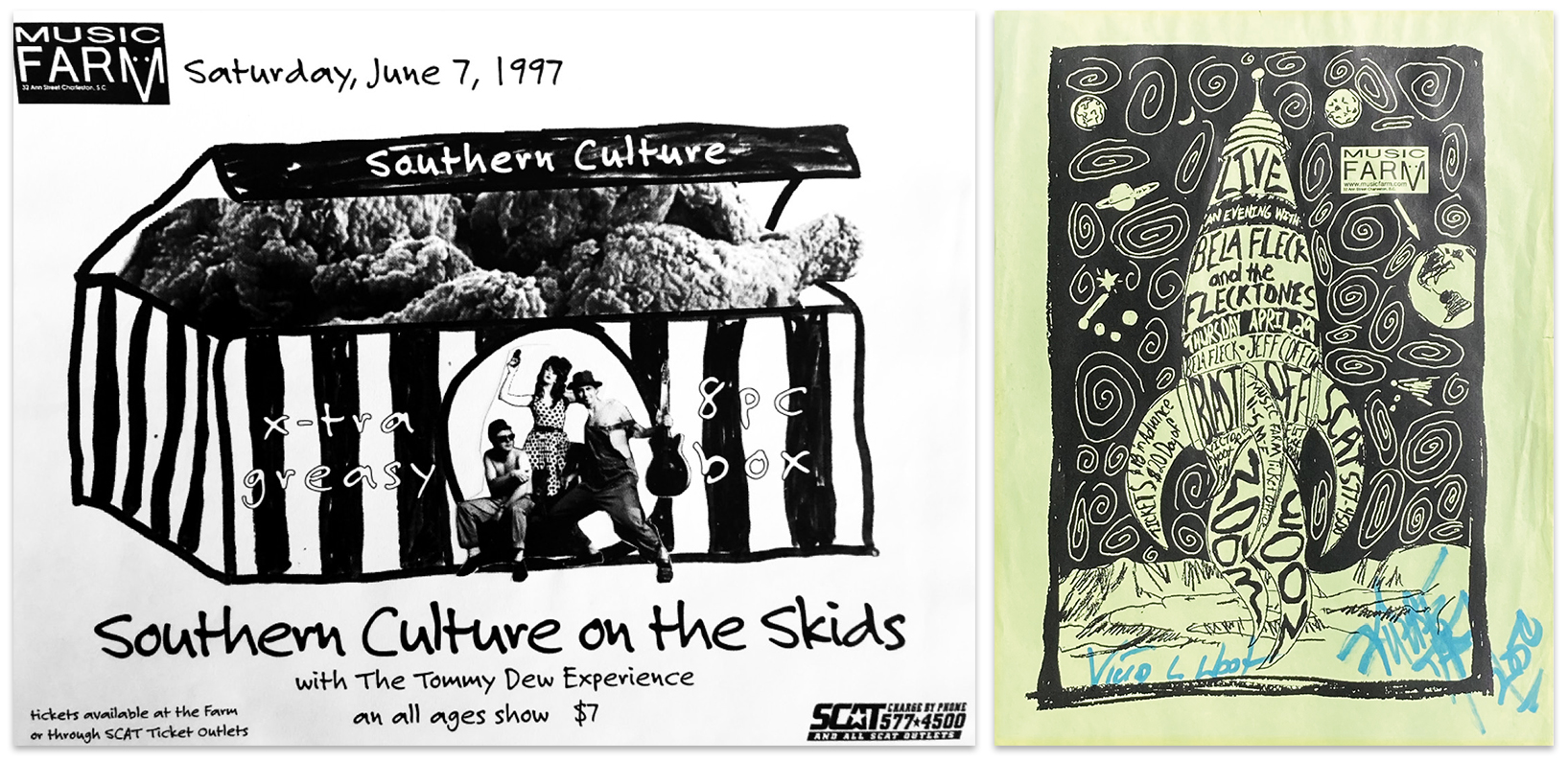

Crowded House: (Above) Stage diving during a 1990s show featuring Raleigh-based funkpunk band Johnny Quest; (Right) Signs of the Times - Graphic designer Gil Shuler, who crafted countless concert posters in the early years, was tapped to design the future Farm’s new branding. He designed the posters shown here, Shuler responded: “Honestly, I think they are all mine. But I’ve done hundreds, and it was so long ago... but I’m 99 percent sure.”

At the end of the initial run in 1998, with the lease expiring, Scheer and Cumins stood at the Music Farm’s bar after a Burning Spear concert, gazed at the curved trusses of the roof, and decided they couldn’t give up the building. They bought it (and still own it) and leased the business to a trio of 20-something music lovers that ushered the Farm into the next century.

“We realized right away how significant a role the Farm played in people’s lives,” says Riddick Lynch, one of the owners from 1998 to 2001. “There was a real collective sense of relief when we bought it.”

The new owners took on the onus to continue a legacy and maintain a reputation. Lynch and his partners brought bands like Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, Blues Traveler, and Ween to downtown Charleston, building the Farm into a place that drew fans from out of town. “Fairly or not, we had the reputation of being jam band-centric, which was partly a reflection of the times but also was working well for us,” says Lynch. “Fans of those bands were fiercely loyal and not afraid to come to several shows a week if they were digging who was playing.”

But despite their success, Lynch’s group felt the same pressures as the original owners. They sold the Farm after three years, closing the deal on the day before 9/11. “Selling the Farm was bittersweet,” Lynch recalls. “Both of my partners were ready to move on to the next chapters of their lives…That business can be a grind with a lot of inherent risk.”

The venue passed through two more ownership groups over the next 20 years, remaining a downtown staple, especially for College of Charleston students. But as the Charleston Pour House on James Island grew its stature with local and touring bands and ’90s legacy bands made The Windjammer their home, the Music Farm became more of an occasional stop for local music fans than a home base.

Throughout the 2010s, from just a block away, the Charleston Music Hall (965 capacity, roughly the same as the Farm) competed for acts, and the comfortable seating, excellent sound, and clear lines of sight made it a preferable venue. Acts like Snoop Dogg, TV on the Radio, and Wu-Tang Clan still provided the occasional sellout at the Farm, but the sense of the room as a hub of the musical community gradually faded.

The Farm’s 2022 rebirth consolidates booking between downtown’s two most prominent music venues. Carmody hopes that between an invigorated schedule and improved patron experience, the Music Farm can harken back to the early days as a place where bands want to perform and fans look forward to visiting.

(Clockwise from top left) The Music Farm under construction in the early ’90s; Renewed Interest - The Music Farm building under reconstruction in January 2022; upgrades include new floors and house and stage lighting, elevated speakers and baffling to improve sound, fully renovated bathrooms, a VIP balcony, and a refinished bar with multiple point-of-sale systems; the recent overhaul as pictured in January 2022.

When the Music Farm closed in March 2020, nobody expected the pandemic to last for more than two years. Beer stayed in the cooler, liquor sat on the shelves, and confetti and trash from the final event—an ’80s versus ’90s dance party—was never swept up. That’s how Carmody and Bonny Wolfe, the senior marketing manager for the Hall (and now, the Farm) found it after assuming the lease in September 2021.

During the 2021 interim period—and throughout the past two decades—owners Scheer and Cumins have received interest from national and big box tenants for the vast space, yet they held out to keep the Farm alive. “This place means something to a lot of 40-year-olds and even 60-year-olds in this town—hopefully it can continue to mean something to the people who are 20 now,” says Scheer. “I think that’s what we’ll see with Frank Productions—a fresh face, some acts that we wouldn’t expect, and improvements that we didn’t have the ability to do.”

Under Carmody’s leadership, the Music Hall has hosted variety shows, TEDx talks, and temporary art galleries—that same type of creative programming may be in store for the Farm. And long-standing grumbles about the Farm—discomforts like the difficulty of getting a drink or muscling your way through the front of the audience to reach the men’s room—are also being addressed.

Staple elements like the central bar and the moonlit mural by David Boatwright behind the stage will remain, but nearly everything else will receive a facelift. The bathrooms will be gutted and rebuilt, including a railing to allow access to the men’s room. Sound baffles along the ceiling will absorb the room’s echo, and elevating the speakers into the air will reduce the sometimes deafening rumble.

On the floor, the sound board has moved to the rear of the room, opening up more space for patrons and eliminating the two pinch-point walkways. The Royal American is taking over the kitchen, elevating the pub grub to a dinner-worthy experience. Most notably, capacity is reduced from 960 to 650 people, improving the listener experience while also allowing differentiation between the Hall and the Farm. “The room will feel more inviting—it should be a place that people want to be,” says Carmody. “We want to welcome the college kids and have shows that are dance parties, but another big goal is to get the 40-and-up former patrons excited to come back.”

Although the Farm will remain general admission and standing-room only, the improved sounds and foot-traffic flow—plus a brand-new HVAC system—should greatly improve patron comfort. “The vibe we want to get back to is that people come because they want to see concerts in this room, or even just hang out and have beers with friends while hearing something new,” says Carmody, who imagines the Farm serving as a base for block parties and a Christmas market. “We want to re-cultivate trust so that people want to come to the Music Farm to check out new bands.”

For its spring debut, the new Music Farm will invite back some of the bands that built their careers in the space, including SUSTO and Stop Light Observations. From there, programming will take advantage of the Farm’s partnership with the Music Hall, bringing in acts that will draw 200 to 600 people and then allowing them to graduate to the theater around the corner as their local audiences grow. Through consistency of programming, Carmody hopes that the Farm can reclaim its importance to the local music scene that it held in the ’90s.

The reopening has also created occasion for the original owners to reminisce. McMillan—now the ombudsman for Charleston County—smiles about his son wearing a Music Farm T-shirt to school and getting called out by a teacher with stories of her own. “It gives me a bit of street cred,” he laughs.

Wadley recalls a B-52’s gig that canceled, and the agent offered David Byrne of the Talking Heads instead—but at an $18,000 price tag. They took the risk on the most expensive show they’d ever booked (and a tiny venue for Byrne), and the night unfolded beautifully. Byrne took the stage in darkness, a spotlight on his face, for “Psycho Killer” and closed the night with Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World.” “At its best, there’s a kick-ass band, and the sound is dialed in,” says Wadley. “When everything comes together, this room can be outstanding.”

(Clockwise from above left) Darius Rucker, Hootie & the Blowfish; Rick Miller, Southern Culture on the Skids; Edwin McCain playing with Uncle Mingo; Kevin Wadley (center), Carter McMillan (far right) and friends with Cracker in the band room at their last show as owners in 1998; The Archetypes.

1991 - 1998

April 3, 1991 Uncle Mingo: “They played the first four nights and rocked the club each time! It was loose and fun with a crowd of mostly locals and College of Charleston students. I think I slept half a day that Sunday.” —Kevin Wadley, co-founder

1991 Hootie and the Blowfish: “They were a great band with original songs and super positive attitudes. If you weren’t having fun at a Hootie show, there was something wrong with you. Plus, the bar sales were by far the largest!” —Kevin Wadley

Fall 1991 Stray Cats: “This was one of our first nationally known acts to play the Farm on East Bay Street. The audience packed in tight, and Brian Setzer and the boys whipped everyone into a frenzy.” —Kevin Wadley

October 1991 “Derek Trucks was around 13 years old, and I got to jam with him onstage! I remember he was playing ‘Little Wing,’ broke a string, and never missed a beat.” —Kevin Wadley

1992 Dave Matthews Band: “Their first show at the Music Farm was opening for Indecision, and we paid them $150. You could tell they were a rocket ship about to take off.” —Kevin Wadley

1992: Social Distortion “A handful of people were stage diving, but one guy just stood in front of lead singer Mike Ness while he was singing. Ness shoved him offstage and said, ‘I don’t go where you work and rock the Slurpee machine.’” —Carter McMillan, co-founder

February 1994 “Counting Crowes opened for Cracker. After their set, the entire band came to the office and asked to use the phone. They had learned of a fan who was in the hospital and couldn’t make the show. They called her over the speaker. It was an incredibly kind thing to do.” —Carter McMillan

February 1994: “Uncle Tupelo played ‘Anodyne’ and were creating a new genre, live in real time.” —Kevin Wadley

February 1994: “Uncle Tupelo drummer Ken Coomer asked for a Music Farm T-shirt. The one he wanted was way up on the wall. I told him if we went to the trouble of getting it down, he had to wear it on their upcoming appearance on Late Night with Conan O’Brien. A week or so later, he called and told me to be sure to watch Conan that night.” —Carter McMillan

May 1995 Pavement: “The indie gods crushed a packed house with opening band, Silkworm, playing Pavement covers. The back of stage was lined with silver tinsel and the entire farm was lit up!” —Kevin Wadley

1995 Southern Culture on the Skids: “They played for us on a regular rotation. For this show, they asked for an eight-piece box of fried chicken on their contract rider. That night, I forgot to get the chicken, and Mary, the bass player, who I adored, suddenly got snippy. She said, ‘Kevin, we can’t go onstage tonight until we have an eight-piece box!’ They used props during their performances, and the chicken was apparently vital. I shot down Meeting Street, and KFC was just closing. I scored a box, and the band played a killer show, and Mary was back to her sweet self.” —Kevin Wadley

February 1998 Run-DMC: “I remember hanging out with Rev. Run and Jam Master Jay in the band room. Once they hit the stage, the whole room started jumping up and down. It looked like the building was literally jumping.” —Kevin Wadley

1998 Group Photo: “Cracker played our last show. Those guys were just great people; David Lowery was especially kind. We opened the bar to everyone at the end of that show and got more than a little banged up.” —Kevin Wadley

(Clockwise from top left) Dave Matthews Band; Janna Jeffcoat (center) with her sister and Bayside; Social Distortion; The Dead South; Run DMC; Brian Setzer Stray Cats; Music Farm crew; Johnny Quest; Gov’t Mule.

2001 - 2020

April 3, 2001 10th Anniversary: “Ween played the actual date of the Farm’s 10th anniversary (and my 30th birthday). Two days later, Gov’t Mule featured Dave Schools (bass, Widespread Panic) and Chuck Leavell (keyboards, Rolling Stones, Allman Brothers, etc.). We had big shows virtually every night of that week to celebrate properly.” —Riddick Lynch, former owner

October 28, 2007 Avett Brothers: (The first show under the ownership of Trae Judy and Marshall Lowe) “Looking back now, I knew that we were embarking on something special having just remodeled and starting with new energy—the rush to get open, it all happened so fast. I do remember standing on those steps and taking it all in for a moment….I had no idea how much fun we were about to have in that room over the next 10-plus years.” —Trae Judy, former owner

May 16, 2009 Snoop Dogg: “Bringing a hip-hop legend like Snoop just hit different. All day the energy in the room was electric and palatable. I grew up on his records, so it was surreal to be throwing the biggest party in town that night.” —Trae Judy

2009 Music Farm crew: “We have always been one big family. We appreciated our team, the fans, and the bands. The same core crew kept the venue a place that bands and fans have never forgotten. I know we are all super proud of that and will never forget our time as custodians of the Music Farm.” —Trae Judy

New Year’s Eve 2015: Jump, Little Children returned to the Farm for the final show of their reunion tour. “It was a wild, raucous rock show with a countdown and balloon drop. It felt like quite a homecoming. We have a huge sense of gratitude toward the Music Farm.” —Ward Williams, Jump, Little Children

May 21, 2017 “Bayside was the first show I ever attended at age 16. And I finally got to work with them!” —Janna Jeffcoat, former general manager

October 31, 2019 SUSTO: “I loved Halloweens at the Farm with our staff. That year, my sister and I dressed up like Elton John. Everyone had a blast.” —Janna Jeffcoat

January 20, 2020 The Dead South: “One of my favorite parts of the job was discovering new music like The Dead South. Their show, just a couple of months before the pandemic shut our doors, was sold out. We were wall to wall with people, everyone singing along to the music.” —Janna Jeffcoat

Listen to Music Farm favorites on the Spotify playlist below:

Though architect Edward Bailey sketched the original Music Farm logo, graphic designer Gil Shuler, who crafted countless concert posters in the early years, was tapped to design the future Farm’s new branding. Taking notes from the historic train depot that houses the venue, the logo takes the shape of the building, with its iconic flower window in place at top center. When asked whether he designed all the posters shown here, Shuler responded: “Honestly, I think they are all mine. But I’ve done hundreds, and it was so long ago... but I’m 99 percent sure.” >>see more posters in the photo gallery

Opening Lineup - The Music Farm reopens next month with Charleston-based bands SUSTO (April 15 & 16) and Stop Light Observations (May 6 & 7), plus alt-rockers Son Volt (April 28), who began playing the Farm in the ’90s. Visit the website for even more upcoming shows.

Music Farm

32 Ann St.

musicfarm.com

Images courtesy of Kevin Wadley; Amanda Bouknight & Courtesy of (Mcmillan & Wadley) Kevin Wadley; (Concert) by Wes Fredsell; (Music Farm present construction) Amanda Bouknight & courtesy of (3) Kevin Wadley; Images courtesy of Riddick Lynch, Trae Judy, & Janna Jeffcoat; Images courtesy of (Sam Bush, Bela Fleck, & Gov’T mule posters) Riddick Lynch, (original logo & 4 posters) Kevin Wadley, & (New Logo) Music Farm; Images courtesy of Carter McMillan; photographs (David Byrne) by Ron Baker, courtesy of Wiki