Molly and George Greene founded the nonprofit in 2001 with the mission that all people have access to safe drinking water

In 1998, Molly and George Greene (above) developed a water treatment system to aid people in Honduras in the wake of Hurricane Mitch. Three years later, the couple founded Water Mission as a faith-based nonprofit. Though Molly passed away in a drowning accident in 2019, her husband and son and their staff, now 400 people and counting, continue to carry out the vision: “That all people would have access to safe water and the opportunity to experience God’s love.”

On the morning of August 14, a fleet of Chinook helicopters swept into southern Haiti, bearing enough water treatment equipment to supply 35,000 distraught residents. Hours earlier, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake had shaken the fragile nation. Already weakened by political turmoil, poverty, and the COVID-19 pandemic, towns subsequently lay in shambles, entire buildings reduced to little more than concrete heaps. Amid the dust, however, one North Charleston-based nonprofit poured out a clear promise of care in the form of clean H2O.

For two decades, Water Mission has mobilized safe water relief during natural disasters around the globe, as well as built lifesaving water systems in underdeveloped regions, where 2.2 billion people live without access to safe drinking water. On any given day inside its 43,000-square-foot Navy Yard warehouse, volunteers work assembly-line style to construct Living Water Treatment Systems. These mostly solar-powered units use a variety of methodologies, including reverse osmosis and chlorination, to remove contaminants and produce 10,000 gallons of potable water a day. From the warehouse rafters hang a vibrant collection of flags representing the countries touched by this faith-based engineering nonprofit. “At the end of the day, those flags are a refreshing reminder that we’ve helped somebody somewhere,” says retired programmerturned-volunteer Geoff Brittain.

From the Ground Up

During a six-month stretch this year, Water Mission responded to a half-dozen international crises, including earthquakes in Haiti and Indonesia, a winter storm in Texas, and back-to-back hurricanes in Honduras. “Where people’s supplies have been disrupted, we focus on immediately restoring access to safe drinking water,” says CEO George Greene IV, whose parents founded Water Mission in 2001.

Disaster response is one of three branches of the group’s essential work. Some 300-plus full-time staffers, most indigenous to their station countries, guide Water Mission’s dayto-day efforts. They zero in on the long-term needs of developing communities in nine countries across East Africa, Indonesia, and Latin America. Supported by another 100 domestic employees, the organization works to bring safe drinking water and sanitation to the 30 percent of the world’s population who lack these basic necessities.

Much of this aid takes place in rural areas that have been overlooked and underserved. Homes don’t have electricity, running water, or bathrooms, and water choices are limited. The time spent accessing far-off sources and the intrinsic illness from unsafe drinking water keep people from more productive pursuits such as school, farming, and other work. In these “last-mile communities,” Water Mission strategically constructs tap stands and sanitary pit latrines, and more recently, in response to the pandemic, thousands of handwashing stations. The simple introduction of clean water for drinking and hygiene produces a substantial trickle-down effect.

“Within a month of bringing safe water into a community, we see the incidence of waterborne disease drop. School attendance increases. Adults can work to generate income. The communities establish a municipal bank account to fund maintenance and expansion of their water system. People realize they’re capable of helping themselves. That’s a huge paradigm shift,” explains Water Mission cofounder Dr. George Greene III. “Water is the linchpin, the key to breaking the poverty cycle.”

Somewhere in between disaster response and community outreach lies Water Mission’s support of the refugee camps in Uganda and Tanzania. “Refugees move because of a crisis, but the average tenure in these camps is estimated to be 10 years,” explains CEO Greene. “We organize immediate access to basic needs, but we also have to plan in the tens of years.”

In the open fields of Nyarugusu Refugee Camp, for example, Water Mission erected a 100,000-watt solar panel to power the treatment and pumping of water for more than 250,000 displaced people. Similar projects have been constructed in two other camps.

The Global Water Crisis

As the longtime regional director of Water Mission’s program in Tanzania, Will Furlong harbors a unique understanding of the trials associated with a lack of safe water and sanitation. “In East Africa, most women and children walk an average of three miles to fetch water outside of their communities. They are frequently raped or molested along the way. Once there, they must often wait in line.” If their water source is a lake or river, villagers also contend with skin-burrowing parasites and crocodiles.

The water they carry back in buckets remains heavily contaminated. “Some try to boil it and others add a chlorine tablet, but those are expensive solutions, so most people just drink the water as is,” explains Furlong, who lives in Dar es Salaam. He tenderly recalls one Ugandan fishing village crowded with malnourished children. “They were beautiful children, smiling, curious, playful. I knew if nothing was done, every one of them would get sick, and the most vulnerable among them would die.”

Half of the hospital beds in developing countries are filled with people suffering waterborne illnesses, yet in the United States, we can access safe water with the touch of a tap. “What’s so striking about this problem is that it shouldn’t exist,” says Dr. Greene, who created Water Mission along with his late wife, Molly. “We have the technology in the developed world to treat any water anywhere.” His son concurs, “We solved the water issue in this country more than 100 years ago. We can fix this.”

A Watershed Moment

George and Molly Greene’s Charleston-based environmental testing lab General Engineering Laboratories (GEL) was deep into its teenage years when Hurricane Mitch hit Honduras in 1998. Seeing news reports of entire villages washed out to sea and feeling compelled to help, Dr. Greene reached out to his only contact in the country, an Episcopal bishop. “My e-mail simply said, ‘What can we do? We know a little about water.’ I honestly didn’t think I’d hear back,” he remembers. But the next morning, an urgent one-line reply sat in his in-box: “We need six drinking water units.”

Unable to locate any ready-made systems he set to sketching on a yellow legal pad. “Water treatment isn’t really complicated, so we thought, ‘Let’s just build something.’” Two weeks later, a small team from GEL had transformed basic hardware-store materials into a half-dozen water treatment systems ready to be airlifted into Honduras. Along with volunteers from their company, the Greenes headed to Honduras the week before Thanksgiving to install the rudimentary systems—the first working prototype of the Living Water Treatment System.“That trip changed our lives,” muses Greene. “We saw conditions that we’d never thought existed.” In one village, the sole source of drinking water was a murky brown river known locally as “Rio de Muerte (River of Death)” for the deadly diseases harbored in its waters.

For the subsequent two years, the couple continued educating themselves about the vast global water crisis. They dabbled in safe water solutions under their company umbrella, sending treatment systems to Mozambique, El Salvador, Turkey, and other nations in need, but quickly realized that the answer wouldn’t be found in a for-profit environment. “On the last Saturday in September 2000, Molly and I sat on our back porch, talking and praying. By the end of the day, we were in agreement,” remembers Greene. The couple planned to sell their company, at the time, the largest privately owned US lab, to focus on water. “We felt this was where the Lord was leading us,” he explains. “We knew this wouldn’t be just a humanitarian group, but a Christian ministry to provide access to safe water while also sharing our beliefs.”

A Lasting Impact

Greene’s PhD in chemical engineering and Molly’s master’s in Spanish proved to be quite a powerful combination. “We ran our forprofit company based on Christian values,” he reflects. “And we run our Christian nonprofit like a for-profit company.” That has meant setting and adhering to quality standards with a strong technical focus. “We aim to put systems in place that will last.”

The founder points back to this summer’s earthquake in Haiti. As part of Water Mission’s response, a team revisited each Living Water Treatment System installed after Hurricane Matthew in 2016. Knowing that Haiti sits on a seismic fault, the organization’s licensed professional engineers designed the structures to withstand future disasters. Of the 40 projects, 38 of them remain functional following August’s quake.

That commitment to getting things right the first time has fueled substantial growth and credibility over the past two decades. The nonprofit assessment group Charity Navigator has bestowed a four-star rating on Water Mission for 14 consecutive years. “Donors and corporate partners recognize our excellence and determination to be best in class, to be sustainable,” says Furlong. “And I think, in our work, they see love.”

A 2017 audit of groups working in Ugandan refugee camps specifically highlighted the nonprofit’s success. “Water Mission stands out as the nongovernmental organization with enough in-house expertise to independently design, operate, and maintain solar water schemes,” reads the International Organization for Migration’s report. At a time when 30 to 50 percent of water, sanitation, and hygiene projects fail after two to five years, “that really validated our approach,” notes George Greene IV. As a result, Water Mission and UNICEF teamed up to publish an installation manual outlining the nonprofit’s standards and instructions to help guide other relief groups.

Perhaps the clearest element of the group’s success rests in its approach to those in need. “We look at people as partners, a value that stems from our faith,” says Furlong. “Our systems are sustainable because villages commit to the project and essentially bless themselves.” When Water Mission engages with any community, it asks residents to provide locally available building materials, labor, and land for structures. Communities also participate in management training for the finished water systems. “When we get to the end of a project, we can say, ‘Look what you have done.’ There’s a sense of ownership, pride, accomplishment, and dignity,” Furlong continues.

The Future is Clear

In its first decade, Water Mission reached one million people in need of safe water and sanitation solutions; now, at the close of its second decade of service, the charity has helped some seven million people across the globe. “That’s a lot of people, and it means a lot to those individuals, but there’s still a huge need,” stresses George Greene IV, explaining that Water Mission’s goal is to grow as fast as possible to meet it.

With 2.2 billion people in need of safe drinking water and nearly twice as many lacking access to adequate sanitation, Water Mission’s impact to date may feel like a mere drop in the bucket, but the nonprofit is laying the groundwork for partnerships to expand their reach. “We believe there just aren’t enough people working to solve the problem. This crisis is so big that it can’t be solved by one organization,” says Dr. Greene. Last year, the group established an international consortium known as the Global Water Center, which strives to pool the expertise and resources of companies such as Kohler (plumbing), OxyChem (chlorination), and Pace Analytical (environmental testing) for a broader impact. By leaning on each other’s successes to bring safe water to developing countries, these groups can more swiftly and efficiently solve this massive problem. “Our vision is that all people would have access to safe water and an opportunity to experience God’s love,” explains Dr. Greene. Asked what the future holds, the resolute founder responds matter-of-factly: “The future holds safe water for two billion, 200 million people.”

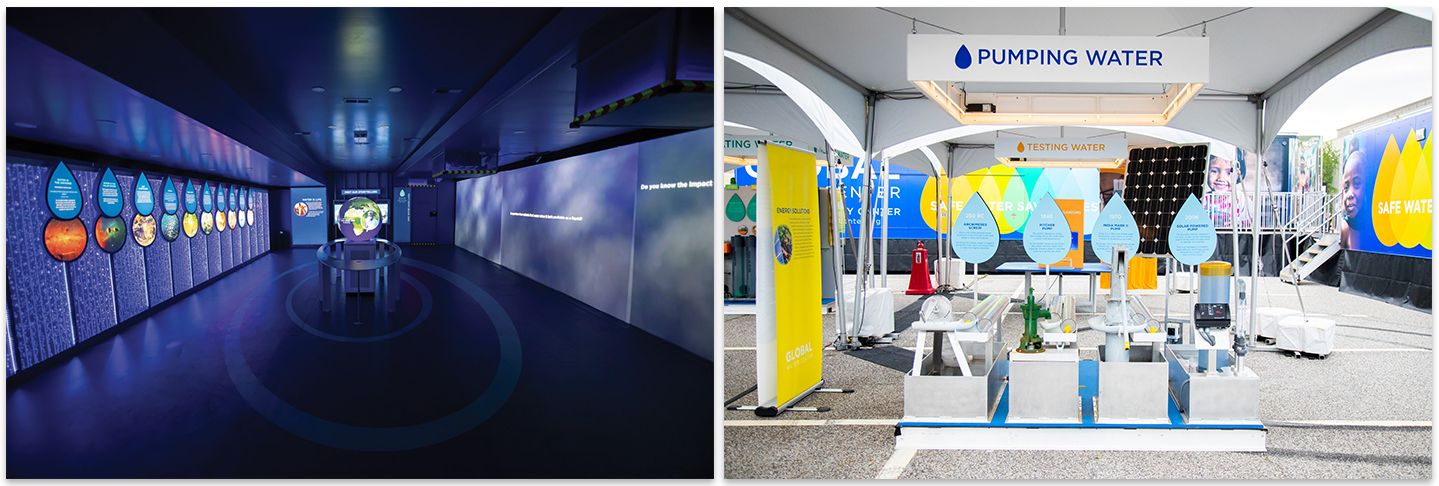

(Left) The first exhibit inside the unit, Water Is Life, illustrates its three states—liquid, gas, and solid; (Right) Outdoor pavilions offer hands-on activities for learning about water testing, solar-powered systems, and water treatment.

The Mobile Discovery Center

In an effort to funnel more awareness of the global water crisis stateside, in January 2020, Water Mission and the Global Water Center set out to create a Smithsoniancaliber experience on wheels. Within 10 months, the Mobile Discovery Center hit the road, sharing water-based knowledge in cities around the country. From toddlers to seniors, visitors have the opportunity to play with pumps, experiment with chemical reactions to remove contaminants, learn about the water cycle, and witness how water treatment works. (The Mobile Discovery Center pulls into Greenville, South Carolina, on December 1 for five days.) “The idea is to educate people on how precious clean water is, help them understand that 30 percent of the world’s population doesn’t have it, and show them there’s something we can do about it,” says Water Mission founder Dr. George Greene III.

In Their Shoes: Walk for Water 2022

Every day, adults and children walk more than three miles to collect water for their families. On March 26, 2022, Water Mission asks Lowcountry residents to walk in the shoes of the more than 2.2 billion people around the world who lack access to safe drinking water. Walk for Water, the nonprofit’s annual fundraiser, raises awareness with a three-mile bucket carry at Riverfront Park in North Charleston. Since 2005, thousands of Walk for Water participants have raised millions of dollars to fund solutions to the global water crisis. Learn more at watermission.org.