The organization is and could serve as a model for reducing recidivism nationwide

When Winard Eady was released from federal prison in November 2019, he vowed not to return to the lifestyle that put him behind bars for eight years. Like most people who’ve been incarcerated, however, he struggled to find his footing on the outside. “I came home with the sense that I wanted to do different,” says the Wadmalaw Island native, who was sentenced to 10 years for his role in a string of business robberies. “But as soon as the world hits, your mind changes.” The numbers prove as much: Two-thirds of people released from prison are rearrested within three years, according to the Justice Department. After nine years, that number climbs to 83 percent.

Facing few job prospects and mounting financial pressure, Eady soon heard the call of the streets, where he knew he could pull down $2,000 a night selling drugs. “One side of my mind said I could do the same thing over again, and I won’t get caught,” he says. Lucky for him, he chanced upon a flyer in a barbershop; it was for Turn90, a Charleston-based nonprofit then called Turning Leaf that supports men reentering society from prison with social services, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), transitional work, and job placement.

Eady gave the 12-week program a chance, working in its screen-printing shop, which offers job training, and excelled, though he admits it wasn’t always a smooth road. Like a lot of people who’ve been through the criminal justice system, he found it difficult to trust others. He’d grown up with an abusive father (who has since turned his life around) in a trailer with no power or running water and, at one point, was catching shrimp, crabs, and fish in a nearby creek for food.

At first, Eady bucked the therapy component. “When I heard the instructor say, ‘When we think differently, we act differently,’ I didn’t want to believe that. I told him, ‘I don’t need you to tell me how to think,’ and he said, ‘We’re just giving you the tools. We can’t make you do anything you don’t want to do,’” he recalls. “That sat with me.”

After completing the program, Eady landed a steady job at a manufacturing company but eventually found his way back to Turn90, this time as an instructor. Once he was trained in CBT, it was his turn to offer tools. “I was teaching emotional-regulation skills, problem-solving skills, life skills, and role-play,” he explains. “All this just to get you ready so if that moment comes where a problem arises, you’ll know how to deal with it.”

Today, Eady, 42, is the program manager for the Charleston center. He estimates he’s seen roughly 70 participants succeed and remains in regular contact with 25 of them. “It’s an amazing feeling,” he says of the community he’s helped to build. “It’s not really a job to me.”

Winard Eady (above, teaching the daily life skills class) discovered Turn90 after being released from federal prison in 2019. He completed the program, found gainful employment, and eventually returned as a classroom facilitator. Today, he’s the Charleston program manager, helping other men reenter the community and build a better life.

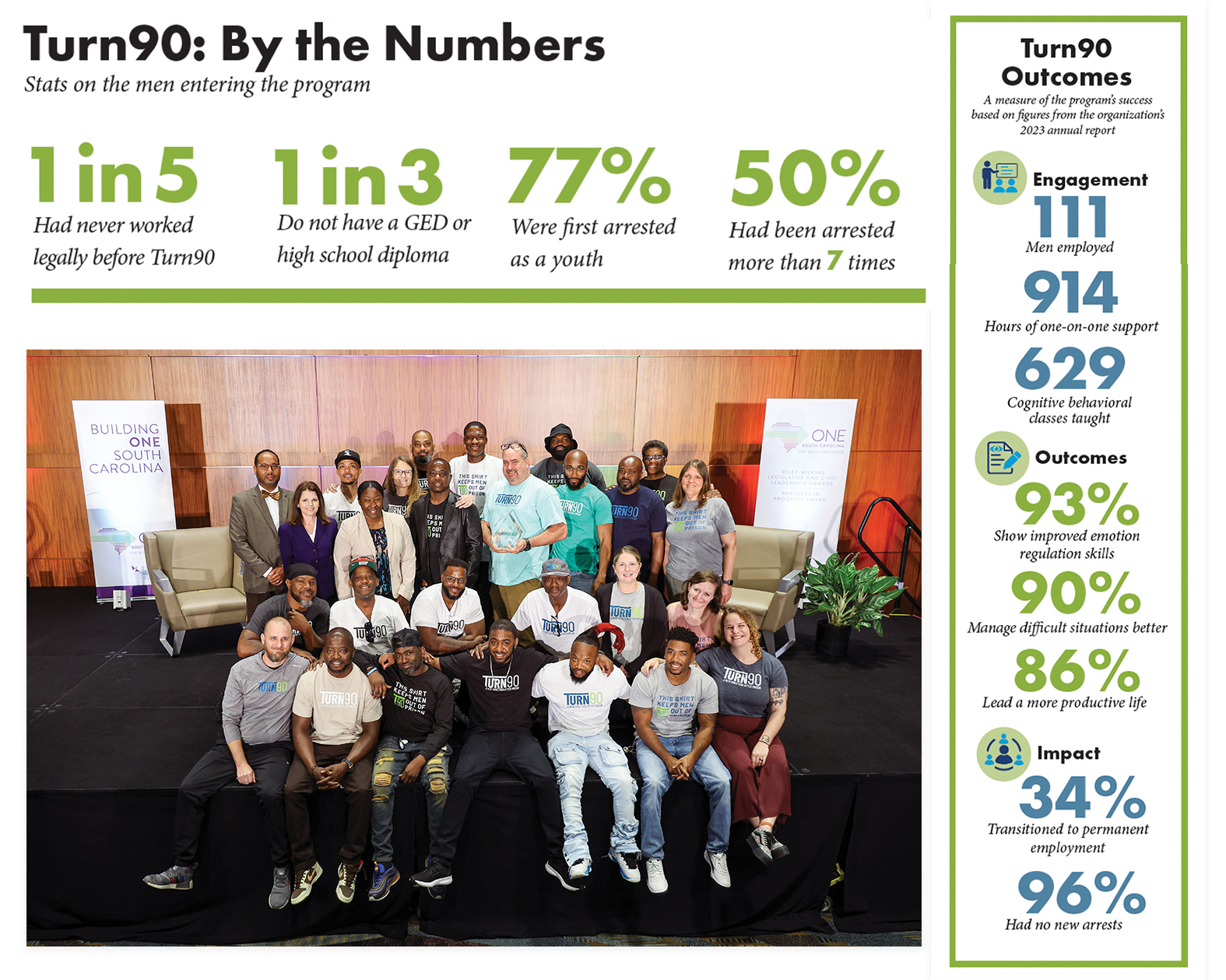

Such is the net cast by Turn90, which the program was rechristened in 2021. US District Judge Richard Gergel calls it “one of the most innovative and successful reentry programs in the country.” Founded in Charleston by Virginia transplant Amy Barch 10 years ago, the nonprofit’s unique therapeutic-social enterprise model has seen 88 percent of its graduates retain employment for 90-plus days and 78 percent of its graduates remain arrest-free.

With that promising track record, Barch and her board of directors replicated the program in Columbia in 2021 and plan to open a third location in Spartanburg by the end of this year. The aim is to ramp up the number of men in the pilot so it can be more rigorously evaluated—and thus, more scalable. Mean-while, they’ve launched Turn90 Logistics, an expansion of their social enterprise arm that provides assembly services, and a new facility for the Charleston center that will double its footprint to 10,000 square feet.

“My life’s dream is to evaluate the model and gift it to the field,” Barch says. “I want people to learn from it and make it better.” Her goal became that much closer when Turn90 beat out more than 6,000 applicants to receive a $2 million grant from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving fund last spring. “Receiving $2 million in seed funding is exactly what we need right now to take Turn90 to the next level,” she said at the time.

“An Angel Named Amy”

Anecdotally, Barch’s work has already been a game changer. “Most of the people we deal with are misguided,” says Gergel. “They’ve grown up with this idea that this is what you do, and Amy tries to show them that there is another path.” The judge first learned of Barch when a defendant who had recurring issues with the law wrote him a letter, saying, “I always thought the problem was other people, but now I’ve concluded it’s not other people, the problem is me.” Gergel was intrigued. “Now, that’s not what I normally hear from defendants,” he says. “So I inquired what prompted him to say this, and he said, ‘An angel named Amy.’”

Hear founder Amy Barch introduce the Turn90 program:

Gergel called Barch into his chambers, where he encouraged her to transition from volunteering in prisons to going all in on a reentry nonprofit and helped her assemble a board of directors. “I was convinced she had something bigger to offer,” he says. “She’s a true visionary.” As for Barch, launching a nonprofit hadn’t been on her radar. “I couldn’t find the organization I wanted to work for so I ultimately ended up creating it,” she says.

As a child growing up in Winchester, Virginia, Barch had always considered herself privileged. The older she got, the more that sense weighed on her. “I knew I didn’t want to use the privilege that was given to me in order to create a life that benefited only me,” she recalls. “That felt wrong.” After bumming around Europe in her post-high school years, she landed at what she calls “a hippie commune” in Spain and had a revelation: “I realized that what I was really going for was a life of service.”

But it wasn’t until she interned at a county jail during her junior year of college at the University of Washington in Seattle, where she majored in law, societies, and justice, that Barch knew what that service would look like. “It completely changed my perspective on who we incarcerate. The differences between us are so thin,” she says. “I thought, ‘This is such a tragedy.’ I knew it was a big enough problem for me to dig into for the rest of my life.”

Barch says that she knew she wanted to hire Winard Eady when she met him: “I knew he was serious about Turn90, and I saw how gifted he was in motivating other men while in the program.” And she notes that his story is not unique: “There are so many guys out there who have been able to overcome these odds in which everything was stacked against them.”

Trial & Error

After a stint working with correctional facilities in the DC area, Barch moved to Charleston in 2010, drawn to the city for its size and climate. She was waiting tables and teaching restorative justice classes in prisons as a volunteer when Gergel prodded her into establishing what was then Turning Leaf.

From there, it was trial and error. Barch’s practice of applied research has been key to refining Turn90’s model. “A lot of my work is taking research and making it come alive,” she says. The most crucial tweak was incorporating a social enterprise element. “For many years, we were just a program that was delivering CBT, supportive services, and some job placement,” Barch says. That formula, however, wasn’t proving optimal. Graduates weren’t staying in their jobs, often leaving in a matter of months or even weeks. Some of these men had never worked legally and any executive functioning skills had deteriorated behind bars, where every decision is made for an inmate. Moreover, many had grown up with little trust in institutions. “They were having a hard time because their life wasn’t structured around what it means to be at work from nine to five,” Barch says. “We saw that being a challenge and thought, ‘Why don’t we be the nine-to-five?’”

Learn about how they are expanding the program, which could become a model for the nation in reducing recidivism:

In 2017, the program launched an in-house screen-printing shop at its facility on Leeds Avenue in North Charleston—an old prison that the South Carolina Department of Corrections leased to the group for $1 a year—as transitional employment to hone job skills and get the men acclimated to structuring their lives to support a full-time job, such as securing reliable transportation. “That’s when things started to click,” Barch says.

The community element proved pivotal. “We call it an ‘immersive environment’,” she explains. “We need to create these therapeutic, immersive, pro-social environments for people when they come out of prison to relearn, or even learn for the first time, what appropriate behavior is and get feedback from people that are their peers and that they trust.”

North Charleston Mayor Reggie Burgess knew Turn90 was onto something when he sat in on a mentoring session in conflict resolution in the early days of the program. Some of the scenarios being discussed rang a bell with Burgess, who spent 34 years in law enforcement before becoming mayor earlier this year and now sits on the Turn90 board of directors. “The program deals with root causes of criminal behavior: we have to go back and figure this young man out, when did we lose him? Once we get the mind focused, once their heart changes, they don’t go back,” he says. “The program gives ex-offenders the opportunity to say, ‘That was me back then, and this is me now.’”

In May, the Turn90 team was honored with the 2024 OneSouthCarolina Partners in Progress Award from Furman University’s Riley Institute for driving social and economic impact in the state.

Leveling the Field

Today, participants divide their time from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. between cognitive behavioral therapy classes and work in the print shop and receive $14 to $16 an hour for the full day, for a total of 35 hours a week. “This isn’t a handout, this isn’t charity; this is us leveling the playing field so [they] have a safety net like everybody else,” says Justin Evans, director of the Charleston facility. “If you work this process, you’re more or less guaranteed a good paying job and a career.”

Turn90 alum Steven Hill had heard about the program at a halfway house in Charleston after serving eight and half years in prison and was all in after talking to Evans. He says reintegration wasn’t easy after being incarcerated for so long. “It takes a lot to adapt. You’re used to a certain structure, a certain set of rules.” The program gave him the tools he needed to acclimate to the outside world. “They basically helped me with my decision-making. They taught me about how to not lose control, how to think things over, and adapt to everything that goes on in your life.” They also helped with practicalities, such as finding an apartment. After working at Urban Electric for eight months, Hill, 37, moved back to his hometown of Greenville in early 2023 and is now a senior machine operator at manufacturer Milliken & Company. “[Turn90] helped me a great bit,” he says. “It got me back to society.”

The goal is to place participants in jobs that pay $18 to $20 an hour, and these days that means public works and manufacturing. Typically, these are employers that wouldn’t be willing to hire the same men straight out of prison based on their criminal backgrounds or lack of work history. But once they’ve completed the program, that’s another story, Evans says. “There are so many employers that want to work with our guys because what they’ve experienced is that these are the nicest guys and all it takes is a little bit of kindness back.”

Last spring, Furman University’s Riley Institute recognized Amy Barch and the Turn90 team with the 2024 OneSouthCarolina Partners in Progress Award for driving social and economic impact in the state. Watch the Riley Institute's video about the organization.

For now, Turn90 focuses only on men who’ve committed financially motivated crimes and doesn’t have plans to accept women or people with addiction issues, who require services outside of the scope of the curriculum. Last year, the program hired 111 men, and this year that number will be 100. To grow, Barch says they need collaborators. “Even if someone gave us all the money in the world, you can’t stand around and do nothing, so we have to have a legitimate business,” she explains. “I’m an expert in reducing recidivism, but not screen printing, or growing a business, or scaling a business.” Ideally, she says Turn90 would partner with large companies, who could outsource a component of their work stream for job training, rather than hiring people straight out of prison, which it may view as a risk. “But if they want to work in close collaboration with us, we would be doing all the vetting; we would hire the person.”

With more than 650,000 people being released from US prisons each year and an unprecedented labor shortage, the plan has real potential as a game changer if replicated nationally, says Barch. “There are companies out there that would benefit by collaborating with us in a way where we could work together to unlock the gifts and talents in our prison system,” she says. “We can find a solution, but we need other people at the table.”

If Eady’s experience is any indication, a national Turn90 program would reverberate beyond formerly incarcerated individuals to their immediate families, whose lives have often been upended. One out of two Americans has had a family member in jail or prison, according to Fwd.us, a criminal justice reform advocacy group. Today, Eady has three daughters, all of whom are flourishing, two in school in Atlanta, and an 11-year-old, who lives locally with her mother. “Their dad has turned his life around to be there for them,” he says. “I tell them they can succeed in anything they put their mind to and to know I have their back, always.”