Throughout history, locals have laid their dead to rest with love, respect, and—at times—unparalleled Charleston style. Today, the Holy City has some of the earliest and most beautiful burial grounds in the country. From the simple headstones decorated with seashells to the eerily commanding 19th-century pyramid mausoleum of William Burroughs Smith at Magnolia Cemetery, here’s a glimpse into the iconography, cultural traditions, and international design trends evident in area grave sites

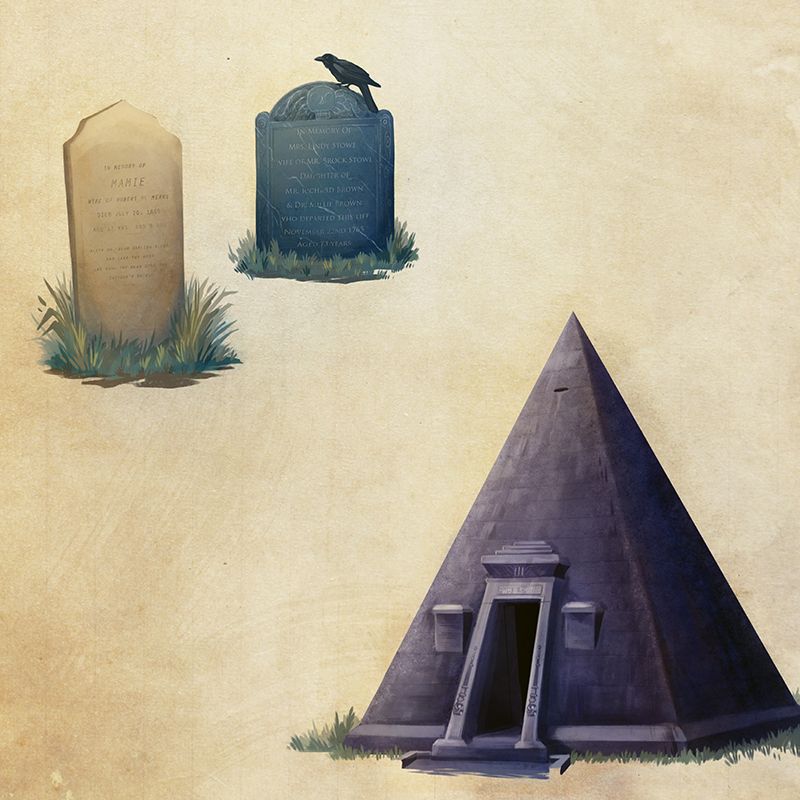

Safe Crossing African-American burials combined elements of Judeo-Christian tradition and African tribal culture. One belief holds that the spirit travels across water to reach the afterlife. Thus many graves are adorned with items associated with water—seashells, bottles, and vases. The Gullah Society is working to rescue neglected burial grounds, such as the one on Monrovia Street where the grave of Mamie (above) is found.

Higher Ground Raised rectangular tombs (usually topped with marble or slate) aren’t unique to Charleston but had a particular importance here: given the area’s extreme lowlands, it wasn’t always possible to dig the requisite six feet deep without hitting water.

Grave Doings By the mid-19th century, graveyards were more commonly called “cemeteries,” a literal translation from the Latin for “sleeping chamber.” There were even tombs designed to look like beds—sometimes the actual bed in which the person died, such as the 1770 “bedstead tomb” in St. Michael’s churchyard, marked by the cypress headboard of Mary Ann Luyten.

Lest We Forget The images engraved into early markers helped tell a person’s story. A broken column meant they died in their prime; an open book described someone with great knowledge; a laurel wreath denoted heroism or distinguished military service; a lily epitomized virtue; and—most poignant of all—a sleeping lamb was for a child.

Wings & Prayers Slate markers—like those from the early 1700s that can be found in Circular Congregational’s churchyard—were often carved with images of allegorical creatures representing death, such as ghoulish grinning skulls flanked by crossbones, hour glasses, and scythes. Later, the crossbones on these “death’s head” gravestones were replaced with wings (at left), signifying the soul’s flight to heaven.

National Treasure The Coming Street Cemetery owned by Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim is not only among the city’s loveliest burial grounds, it’s also the oldest Jewish cemetery in the South. Established in 1762, it contains more than 500 graves, though only some are marked by tombs, obelisks, columns, and other stones.

Park Days Charleston’s churchyards were nearly filled to capacity by the mid-1800s, when a new type of burial place evolved—one designed as an ornamental park. Established in 1850, Magnolia is a superb example of the Victorian rural cemetery created as a destination unto itself. Here, a family could enjoy a Sunday outing (along with relations who had already passed on) amidst meandering walkways; lakes; and gravestones and sepulchers graced with often-elaborate sculpture (take William Burroughs Smith’s mausoleum, below, for example).