Dolphin sightings in local waters are always magical, but these enchanting marine mammals face serious challenges. Get to know our cetacean neighbors and find out how to help keep Charleston’s resident dolphins—that’s right, they stay here year-round—happy and healthy

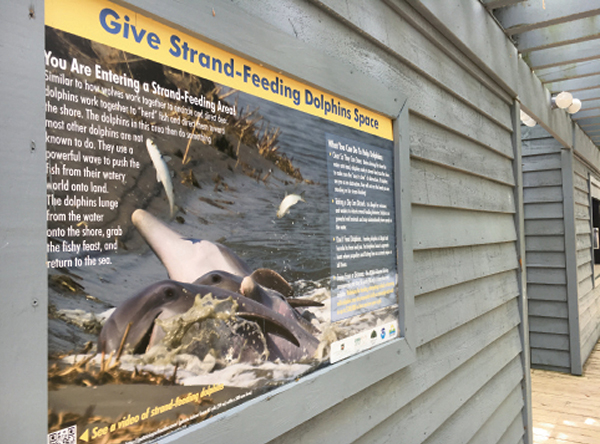

PHOTO: Alfresco Dining: Some of Charleston’s Atlantic bottlenose dolphins are known for a unique, learned behavior called “strand feeding,” which entails herding fish onto a bank, then momentarily “stranding” themselves on shore to catch their dinner.

The sun was barely up on a steamy summer morning, Charleston’s harbor still calm and drowsy, but the docks at Ripley Light Marina were bustling. Scientists from Georgia, Florida, and the nearby Hollings Marine Laboratory scurried about, loading four boats: sterile tubes for blood samples, ultrasound equipment, a special crane-loaded scale, measuring tape, stethoscopes, tissue-sample collection materials, waterproof file boxes, cameras, clipboards, notebooks, water bottles, sunscreen, and coolers—yep, those too. Only these were reserved for biological research materials, not beer.

The crews included some of the nation’s top marine mammal biologists from the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Charleston Center for Coastal Environmental Health & Biomolecular Research, as well as scientists from Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University and the Georgia Aquarium, all of whom were collaborating on Health and Environmental Risk Assessment (HERA) research, a decade-long project comparing the health of Charleston’s resident wild Atlantic bottlenose dolphins with those in Indian River Lagoon, Florida, and ultimately comparing these wild populations with captive dolphins in managed care.

That’s right, our resident dolphins—Charleston’s own estuarine “stock,” as NOAA Fisheries identifies the 300 or so animals that live year-round in local waters. The particular geography of our area, with five rivers and a harbor all leading to the Atlantic, is optimal feeding and breeding grounds for dolphins, and ours, like other bay, sound, and estuarine stocks along the coast (in contrast to migratory wild dolphins) are content to stay within our inshore waters. “A ‘Charleston’ dolphin is highly adapted to our area, able to competently navigate these inshore waters, find enough food to survive and thrive, and have opportunities to mate and thereby reproduce, all the while trying to avoid natural and unfortunately increasing man-made threats,” says Eric Zolman, a local researcher with the National Marine Mammal Foundation. “If ‘our’ dolphin population takes a nose-dive, from disease, habitat loss, and/or harassment, there isn’t a ready pool of dolphins nearby to replace them.” The fact that our resident dolphins are relatively long-lived and in proximity to a national marine science lab makes them excellent longitudinal research subjects.

Zolman and his NOAA colleague Todd Speakman have been keeping tabs and photo-identifying our dolphin residents, a cataloging that dates back to 1994. They know their ages (life-spans average 25 to 35 years), number of calves, and even some of their personalities and behaviors, including which animals are prone to strand feeding (more on that to come). When 36-year-old dolphin “Number 864” was spotted and photographed recently, Zolman was elated: he’d rescued this nine-foot-long creature 15 years ago when Number 864 was entangled in crab line (the top cause of local dolphin strandings).

That particular morning of the HERA outing was back in August 2013, one of the last days in an eight-day series in which this multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional brigade cruised along the Stono, Ashley, and Cooper rivers and in the harbor to study our cetacean neighbors. The HERA team members were both energized and weary, and the dolphins, it appeared, were onto their tricks. As the day went on, the clever marine mammals seemed to have mastered evasion techniques. Ideally the plan went something like this: scouting boats would radio when dolphins were sighted, then research vessels swooped over to corral them within a floating enclosure. After a quick, gentle “capture” and initial assessment to ensure the animal was not pregnant and/or overly stressed, the scientists would carry out a rapid series of masterfully choreographed tests and measurements, then release the dolphin. By late afternoon that day, the teams had successfully tested only two dolphins. “I think they put the word out to lay low,” more than one of the researchers suggested.

What Dolphins Tell Us

This sense that dolphins are intelligent, communicative beings is partly why humans are so drawn to Tursiops truncatus, why we turn and look with awe, marveling every time we hear a damp, gusty exhale as a dolphin curls up out of the water in pearly gray gorgeousness. Glistening and graceful, with their piercing eyes and perpetual coy grin, they appear so friendly, so knowing. With a powerful kick of their mermaid tail, they maneuver between worlds—the deep blue beneath the surface, then above it too, arcing into our realm, breathing our same air.

No wonder dolphins have been the darlings of Hollywood—the ever-chipper Flipper, our playful, trustworthy Lassie of the sea. No wonder people pay top-dollar for the bucket-list experience of swimming with dolphins, or that those out in boats or kayaks might try approaching them—to appreciate their majesty and allure up close and personal.

Indeed, dolphins are rightly considered “charismatic megafauna,” and if any species got an extra dose of charisma, it’s these sleek, smart mammals. Local author Mary Alice Monroe based a series of novels on this uncanny sense of rapport humans feel with dolphins. Writer Susan Casey has similarly fallen under the spell of dolphin magic, and in Voices of the Ocean, explores the mysteries and wonder they evoke, including their language. “Their whistles and clicks and squeals seemed to me like a liquid symphony, a communiqué from another realm, a galaxy of meaning conveyed in a language that defied translation,” she writes. Whether we can actually communicate with dolphins is irrelevant; even without language we sense a deep connection with them. And according to the scientists involved with the HERA study, we are right. On both counts.

“These wild dolphins are trying to tell us something, and we are not listening,” comments Dr. Gregory Bossart, a lead investigator for the HERA study and chief veterinary officer at Georgia Aquarium, in an article announcing the study findings. Sentient or not, dolphins are undeniably sentinel creatures, and this is in part why scientists like Bossart and his Charleston-based NOAA colleague Dr. Pat Fair, who organized the local HERA excursions, study them.

Bottlenose dolphins are not only the most common marine mammal resident in our coastal areas, they are long-lived, apex predators, which means the toxins they ingest bioaccumulate and are representative of toxins within the marine ecosystem and food chain. In short, we are connected to dolphins not just because their cuteness tugs at our heartstrings but because their health is a bellwether for our own. “As a sentinel species, dolphins are an important way to gauge the overall health of our oceans. If wild dolphins aren’t doing well, it could also indicate future impacts to ocean health and even our own health,” Bossart adds.

Fair, who now works with MUSC, published her research results last May in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE, the first ever comparative study of managed versus wild dolphins to show the connection between human-caused environmental impacts and dolphin health. Fair’s abstract concluded that “the marked differences in the immune and endocrine systems of wild and managed-care dolphins appear to be shaped by their environment.” This is concerning, as the immune and endocrine health of dolphins is integral to their reproductive health, as well as to their ability to fight pathogens, such as the deadly morbillivirus or Brucella pathogen that killed hundreds of dolphins along the East Coast from 2012 to 2014. In addition, researchers documented high levels of human-introduced organic chemicals and carcinogens, likely from industrial and nonpoint (indeterminate) sources, in the Charleston dolphin population; less than half of the population was considered clinically “healthy.”

Adaptability & Outreach

This last HERA assessment was back in 2013, which begs the question: what’s been happening since then? A serious game of musical chairs at the Hollings Marine Laboratory, for one thing. The Fort Johnson-based facility is home to an ocean of acronyms—NOAA, NOS (National Ocean Service), NOAA Fisheries, NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology), NMMF (National Marine Mammal Foundation), SCDNR (Department of Natural Resources), MUSC, and CofC, among others. Federal funding for many NOAA projects has eroded, not unlike the shorelines within their purview, and in response, local scientists doing dolphin-focused work have shifted affiliations based on where they can find funding.

Over the years, Wayne McFee, who manages the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science’s marine mammal stranding assessment program (i.e. evaluating dead animals that have washed up on shore, including performing necropsies) and used to do so with a staff of 15, has seen his budget slashed and his team reduced to one—him. “We’re interested in evaluating the stressors on our dolphin population—what are the impacts of aquaculture or tourism, for example. We have to look at strandings to determine this,” McFee explains. Not only has funding shifted or disappeared, many of those who are still at Hollings Marine Lab, such as Zolman and Speakman, have had their allocations diverted to projects related to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, not spent on research related to our resident dolphins.

“It was an abrupt transition in 2010. Overnight, our work here on dolphins’ reproductive health stopped and has been on hiatus ever since. Deepwater is a cautionary tale, for sure,” Zolman says. “We’ve seen disastrous effects to dolphins in the Gulf, as well as to other wildlife. And though the oil spill has not directly impacted our local animals, the repercussions are felt here in the sense that we’ve been pulled away and are limited in our ability to monitor what’s going on with our own population.”

Fortunately, our local dolphin scientists seem to be as adaptable and savvy as their subjects are. Case in point: in the face of severe cuts, Wayne McFee suggested to his former staffer and CofC marine biology graduate, Lauren Rust, that she start a private nonprofit that could assist with stranding responses and resume the marine mammal protection education and outreach efforts. “So that’s what I did,” says Rust, now executive director of the Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network (LMMN), a 501(c)3 that she founded in 2017 to protect marine mammals through science, conservation, education, and outreach.

“We’re a bridge between the hard-core scientists and the community, trying to create awareness about issues facing marine mammals,” explains Rust, who holds a masters in ecology. In addition to helping McFee with strandings (their purview is the whole state; South Carolina averages around 50 strandings a year, the majority of which are in the Charleston area), Rust’s primary focus is studying and protecting Charleston’s strand-feeding dolphins, work supported by grants from the towns of Kiawah and Seabrook islands.

From Strandings to Strand Feeding

“Strand feeding is a unique learned behavior, and Charleston is one of the few places in the world where dolphins are known to do it,” says Rust. It’s an astonishing spectacle to see these animals work together to herd mullet and then, in a meticulously choreographed split-second, create a wave washing the fish on shore before hoisting their 400-pound bodies on to the river bank, where the trapped fish meet their demise. Sometimes the dolphin will do a tail slap to stun the fish first. And because it’s both a rare and remarkable behavior, humans, understandably, are curious and eager to watch.

Yet not only is this feeding strategy highly unique and dramatic, it’s risky. The dolphins expend a great deal of energy to secure this food source, making themselves vulnerable. People who approach the dolphins on the shore or in a boat, hoping to get a closeup photo, or worse, to touch them, can disturb and stress the animals. “The dolphins might leave instead of feed, which then impacts their daily energy budget—the amount of energy they allocate for feeding, traveling, and resting,” Rust explains. And because strand feeding is a learned behavior, anything that interrupts or dissuades the dolphins might break the generational transmission of the clever technique.

To make sure the public understands the risks to the dolphins and the legal requirements established by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, Rust coordinates and trains a network of some 10 volunteers who commit to four-hour shifts (the two hours before and after low tide) a few times a month, in order to provide daily monitoring during peak season (four times a week from October to May). The volunteers patrol the shore along the waterway between Kiawah and Seabrook islands where strand feeding is common. The feeding behavior is geo-specific; dolphins seek out sloping banks with large tidal ranges for successful strand feeding.

In addition to taking notes and photo-identifying any dolphins they spot, Rust and her team approach beachgoers to create awareness about dolphin harassment and make sure onlookers obey federal laws requiring them to keep ample distance (50 yards away when on the water and 10 yards away on shore; see sidebar opposite). Their goal: protect the dolphins by reducing incidents of human interaction and disturbance. Part of Rust’s work and research also involves tracking seasonal trends of both dolphin and human behavior. To that end, in late April 2018, LMMN partnered with South Carolina Aquarium to sponsor a region-wide Dolphin Count (see sidebar, page 121), where “citizen scientists” recorded any dolphins spotted from 12 stations along our rivers and coast.

According to Rust, there’s definite need for more awareness about appropriate dolphin interaction: “I’ve seen people try to touch the dolphins, feed them, or get in the water with them. Sometimes kayaks surround them and block them in. I’ve seen mother and calves get separated.” It’s also unsafe for humans, she notes: “Dolphins seem curious and friendly so people assume it’s okay to interact with them, but they’re still wild, strong, and unpredictable animals. They are wildlife.”

VIDEO: Dolphins Beach Themselves To Feed | The Hunt | BBC Earth

Pressure & Protection

Rust and her colleagues who work to better understand and protect our fine finned neighbors ultimately hope that pressures from development and environmental degradation will not cause undue harm to Lowcountry dolphins. But the concerns are real: Toxins and microplastics are harming their food supply and their health. The BBC Earth documentary Blue Planet II included a segment about College of Charleston scientists who discovered plastics for the first time ever in dolphin guts, right here in Charleston. And the threats aren’t just in the water: Land development, such as those potentially at Captain Sam’s Spit on the southern tip of Kiawah, will increase the risk of heightened human encroachment on dolphin feeding habitat, especially for our intrepid strand feeders.

The threats to dolphins are just as real as the thrill of seeing them slink and roll along the water’s surface, aquatic ballerinas of speed, agility, and mystery. We need their reliable smiles as much as we need their wildness and beauty. And as Rust, McFee, Zolman, Fair, and others who study our resident dolphins agree, they need our protection.

FinBase

NOAA developed the “FinBase” database to store and manage sighting information from field surveys being conducted around Charleston. Dorsal fins with acquired markings—blemishes including scars, nicks, and notches—are visible in digital images and used to distinguish and catalog individual dolphins.

Through a combination of cataloging photo-ID information into FinBase to the hands-on HERA capture-release projects (above left, an adult female being processed in the Wando River in August 2005), scientists are gathering data related to dolphin health and their interaction with their environment.

The Grand Strand Feeding

Strand feeding, basically a highly choreographed fishing expedition, is most often observed around low tide and in places where there’s a sloping bank, usually along a creek or river bank. The dolphins work together to corral the fish (usually mullet) and swoosh them on shore, where the dolphins then hoist their 400-pound bodies out of the water—always on their right side—to catch them. “You can always tell a strand-feeding dolphin,” says Lauren Rust of Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network, “because their right side is all scratched up from oyster shells.” This feeding strategy is taught by mother to calf. When an adult dolphin, independent from her mom since 2006, is observed strand feeding with her mother (below), “that’s pretty cool,” says Rust.

From Research to Outreach

Rust and her Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network (LMMN) volunteers coordinate beach patrols and various outreach programs to educate the public about dolphin protection. This past April, LMMN hosted its inaugural one-day Dolphin Count, during which 34 volunteers coordinating 300 participants spotted a total of 147 Atlantic bottlenose dolphins, as follows:

Brittlebank Park: 2 adults

Coast Guard Station: 5 adults, 2 calves

Charleston Harbor Resort & Marina: 8 adults

Demetre Park: 34 adults, 2 calves

Fort Johnson: 34 adults, 3 calves

Fort Moultrie: 9 adults

Breach Inlet: 22 adults, 5 calves

Mount Pleasant Pier: 6 adults

Shem Creek Park: 2 adults

Wappoo Cut: 2 adults

Waterfront Park: 6 adults

South Carolina Aquarium: 5 adults

Be Dolphin Smart

To minimize wild dolphin harassment, especially by tour companies or those promoting commercial dolphin-viewing opportunities, NOAA and the National Marine Sanctuaries program created guidelines based on the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, using the acronym “SMART”:

■ Stay at least 50 yards away (for vessels; 10 yards if people are on shore).

■ Move away cautiously if animals show signs of disturbance or distress (circling, rapid breathing, vocalizing, splashing, and jumping).

■ Always put vessel engine in neutral when dolphins are near.

■ Refrain from feeding, touching, or swimming with wild dolphins.

■ Teach others to be Dolphin SMART and not to harass wild dolphins.

Other ways that residents and visitors can help protect our resident dolphins:

■ Explore volunteer and support opportunities at Lowcountry Marine Mammal Network (wwww.lowcountrymarinemammalnetwork.org).

■ Learn more about the health of our waterways and the Charleston Harbor Watershed as well as efforts to monitor and protect it by the nonprofit Charleston Waterkeeper (charlestonwaterkeeper.org).

■ Reduce your use of single-use plastics (bags, straws, bottles).

Photographs by (dolphins strand feeding) Ed Konrad, (HERA 2013 outing-2) Stephanie Hunt, (1) Tori Kallman, (portraits-3) Margret Wood, (9) Lauren Rust, (4) Richard Ellis, (1) Patricia P. Schaefer, (1) Kevin McCarthy, (1) Handcraft Films, (4) Melinda Smith Monk, & (Shem Creek) Eric Mills & courtesy of (disentangling) Savannah State University & (capture & release) NOAA