Revisiting the Holy City's forgotten buildings and discovering the lessons they teach us

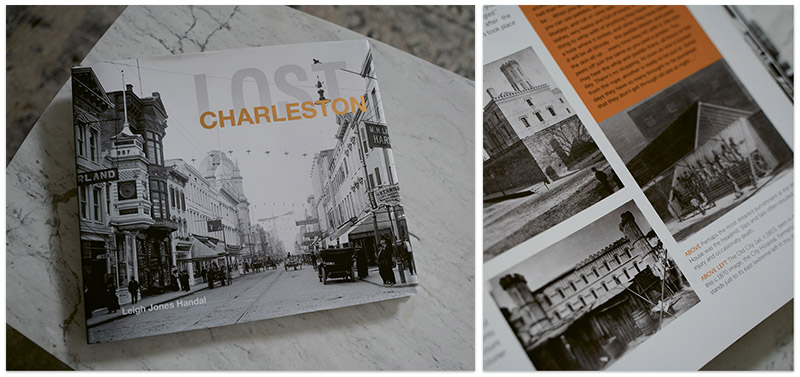

Sense of Place - In her book Lost Charleston, preservationist Leigh Jones Handal takes readers on a tour of the city’s streets as they once were, including The Orphan House—with its grand edifice, cupola, and Palladian and Renaissance Revival architectural details, often cited as one of the most significant buildings that time has erased.

Three nearly identical single houses at the corner of Calhoun and East Bay streets known as the “Three Sisters” came to symbolize the essence of everyday 20th-century life in Charleston, inspiring artists and igniting the passion of preservationists. Despite this, the homes were condemned and demolished by the city in the 1960s.

“The fate of the Three Sisters embodies the tragedy of failing to appreciate something … until it’s gone,” preservationist Leigh Jones Handal says. Her debut book Lost Charleston (Pavilion, September 2019) features decades-old photographs and narratives of 59 institutions that were destroyed by war, natural disasters, or human impact during the past 250 years and poses a larger question: What can we learn from their existence and demise?

A native of Cheraw, Handal felt a deep connection to the Holy City from her first visit as a Brownie Scout. After graduating from College of Charleston, she worked as public programs director for the Historic Charleston Foundation, and now owns the tour company Charleston Raconteurs.

In Lost Charleston, Handal guides the reader through the city as it once was, highlighting such structures as the Orphan House, the first municipal-run orphanage for white children in America. Built in 1794 on what is now Calhoun Street, the grand building, once visited by presidents, was torn down in 1951 and replaced by a Sears department store and is cited as one of the most regrettable losses by members of the Facebook group Charleston History Before 1945—which Handal relied on to research her book.

Handal delves deeper than romantic, “soft focus” images of Charleston, which depict its history through the lens of a rosier, post-Civil War era. One powerful example is the Work House, located near the Old City Jail on Magazine Street and sometimes called the “Sugar House” due to its origins as a sugar factory. According to Handal, people are reluctant to reckon with the building’s past (“The history is too awful,” she says) for enslaved people were sent to the Work House to undergo dehumanizing corporal punishment when plantation owners chose not to deliver the abuse themselves. Following emancipation, the Work House served as hospital, and after incurring damage in the Great Earthquake of 1886, was later demolished.

“A lot of people are uncomfortable talking about it, but you can’t discuss Charleston history without addressing the impact of slavery here,” Handal says. “That period defined who we were, and it continues to impact who we are as a community today.” The many ghostly structures compiled in Lost Charleston characterize the Holy City’s beautiful but fraught past—one that deserves to be revived and examined.

Book Signings

November 13, 5:30 p.m., Buxton Books, 160 King St.

November 14, 6:30 p.m., The Pavilion at Middleton Place, 4300 Ashley River Rd., registration required

November 23, 1 p.m., Cistern Yard, College of Charleston

Photograph Courtesy of Library of Congress