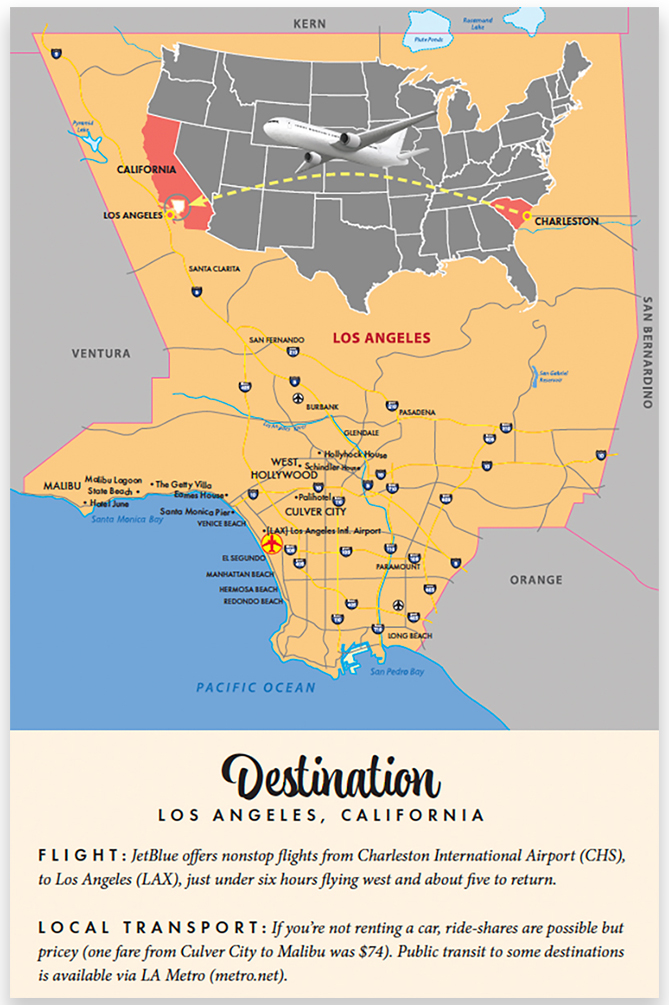

For the second of our One-Flight Wonders series, we’re getting a taste of iconic SoCal style

During the short ride to a breakfast spot, I already spy palm trees and golden sunlight, and our Uber driver is talking about Brad Pitt.

She’d just read that the Hollywood A-lister sold his mansion in the Los Feliz neighborhood to oil heiress Aileen Getty. He then turned around and bought Getty’s much smaller mid-century modern house, a steel-and-glass residence perched on the hills of the same neighborhood. I like this story—not just for an excuse to daydream about a favorite actor, but to muse about how and where people live, the design choices they make. The driver explains that looking at swank house listings online is a daily ritual of hers—and it’s an apt topic of conversation considering the chock-full itinerary photographer Peter Frank Edwards and I have devised. Over three days, we’re going to check out some of LA’s landmark houses. Maybe we’ll pick up a design idea or two to bring home.

CULVER CITY START

We’re here for the bold eye candy of LA. But first, we stop with our carry-on bags still in tow at Destroyer, a minimalist, Scandinavian-style café on a quiet Culver City street. It’s a warming, restorative start on this cool morning as we indulge in deep bowls of rice porridge with roasted leeks, black garlic, and a poached egg.

Taking advantage of the three hours “gained” by flying west, we ease into the day. Culver City was recommended as a home base for its convenience to the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX is within about seven miles) and its location just east of Venice Beach. Our boutique hotel lodging, Palihotel Culver City, neighbors a primary school and charming, tree-lined streets of mid-century houses—while just around the corner are the gated lots of Culver City Studios and Sony Pictures Studios on busy Washington Boulevard. (For movie buffs, popular daily tours are offered at Sony, where The Wizard of Oz and many other classics have been filmed.)

We easily spot the blue-painted Palihotel and its floral kaleidoscope mural spanning a three-story wall. It’s still too early to check in, so we drop our bags and set out for a little exploring in the walkable neighborhood that we quickly discover has a trove of restaurants, local shops in the mod-industrial Platform center, and a new Erewhon grocery (like an amplified Whole Foods). That’s good, because we’re navigating sprawling LA without a rental car on this trip—opting to walk and use Uber to get around.

PCH TO THE VILLA

By early afternoon, we’re motoring up the Pacific Coast Highway gazing out at wide beaches and the blue Pacific on one side, and tall bluffs and hillsides on the other—often in profusions of orange and red wildflowers thanks to the state’s particularly rainy spring.

Almost to Malibu, the driver turns up a steep road that winds to the Getty Villa. Built in the 1970s by billionaire industrialist and art collector J. Paul Getty, its grand, classical architecture is modeled after a 2,000-year-old Roman villa. Admission is free—simply book online for an open arrival time—to visit the property’s galleries of Roman and Greek statuary and other ancient art.

A dramatic reflecting pool leads to ocean views and is often photographed, but the villa’s “aromatic gardens” in another section are what I’m drawn to. Blooming and lightly sweet smelling, it’s an orderly lineup of rectangular, raised beds with markers identifying the plants growing in the ocean air—yarrow, lavender, horehound, rosemary, artichoke thistle, and foxglove—with blossoming quince and plum trees at the edges.

EARLY-MODERN NEAR MELROSE

The next morning, we open the French doors in our room at the Palihotel to sip our coffees outside in the courtyard of palms and butterfly canvas chairs. It’s another bright Southern California day, and our first destination is West Hollywood. When we arrive at Kings Road near the super-luxe shopping district at Melrose Place, I can’t see the Schindler House from the street—only trees, tall grasses, and towering bamboo—because the roofline is so low and it’s set back in the large lot. Meanwhile, at addresses on either side and across the street are multistory mansions built almost to the lot edges.

Viennese-born architect Rudolph Michael Schindler and his wife, Pauline, were breaking new ground in construction and design concepts when they began building this as their home and studios in 1921. The project was a shared vision for the couple, as Pauline’s interest in a revisionist lifestyle led them to create the house “as an experiment in communal living.” The Schindlers shared the space with another couple and various guests, and the property is considered a landmark of the California modernism movement—a design ethos based on clean lines, large windows and openings, minimal ornamentation, and a strong connection to nature.

With concrete floors, wood-beam framing, and paneled walls, the rooms at the Schindler House lead into one another with few hallways and jut out in different directions. Sliding doors open to private patios, sunken ivy gardens, and outdoor fireplaces. The house is open for tours by appointment, and while we’re there, a few other visitors are also exploring, walking from room to room and speaking softly in German.

It’s a rustic, fascinating house that from the start was a gathering place for artists and has been studied ever since for its modern design. By 1952, Schindler reflected on what he’d built, “I introduced features which seemed to be necessary for life in California: an open plan, flat on the ground…glass walls, translucent walls, wide sliding doors. These features have now been accepted generally and form the basis of the contemporary California house.”

EAMES: A CASE STUDY

For many people, the Eames name conjures images of molded plywood chairs—variations of the iconic design have been produced since the 1940s. Art, architecture, and furniture design—husband-and-wife team Charles and Ray Eames gained fame among the 20th-century visionaries and rule breakers, designing in new ways. Their house is up next.

It takes effort to visit the Eames House, both in planning and to physically get there. Ticket releases are limited, announced online by the Eames Foundation. After walking uphill to the very end of a narrow, private street on an ocean-facing bluff in Pacific Palisades, we arrive at a gate and wait with a few others for a guided tour to begin at the couple’s longtime personal residence.

Skewed to one side of the 1.5-acre lot to preserve an open, grassy meadow, the circa-1949, two-story house and studio with a welded metal frame features lofty interiors and rectangular shapes—a flat roof, tall glass windows, and panels painted in mostly primary colors, connected by patios arranged with potted plants. (The Eameses liked to change out and move plants often, the guide explains.) This is one of the “Case Study” houses built in the 1940s and ’50s as a program of California-based Arts & Architecture magazine to challenge architects to rethink how houses could be designed and constructed, often using techniques and materials first developed in the World War II-era.

The Eames House is a showcase of such materials—a corrugated glass interior wall, square kitchen tiles of rubber vinyl, recessed lighting (new at the time), and expansive panes of glass in dimensions larger than had been created before. Lines of sight from inside the house flow directly to the eucalyptus trees and poppies outside. Here, too, the green areas far exceed the indoor space. (The house is 1,500 square feet, and the studio 1,000). It’s amazing to think how impactful this compact design has been. The Eames House has been visited, studied, and written about extensively, and the guide explains that architects and designers often fill the consistently sold-out tours for firsthand views and inspiration.

HOLLYHOCK VISTA TO SURF VIBES

On day three, we’re headed out early for one more architectural must-see—an East LA hilltop park where the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Hollyhock House is perched next to a grove of tall pine trees. It’s at the center of the city’s 36-acre Barnsdall Art Park, where picnickers and sun worshippers stretch out on blankets in open areas.

Constructed between 1919 to 1921 for oil heiress Aline Barnsdall, the structure can look and feel more monument than house—cast concrete, obelisk-like adaptations of the hollyhock flower outside and substantial, detailed wood paneling inside. Deemed a “harbinger of California modernism,” the site is also popular with international visitors—we meet a couple from Brazil in town for a wedding, who said, “We had to make time to see this famous house.” And everyone who enters is required to slip on disposable overshoe slippers to protect the century-old flooring.

Here, I’m struck by the vantage point. From grassy courtyards at Hollyhock, downtown streets extend out in the valley below, and the landmark Hollywood sign and Griffith Observatory are easily seen in the distance—a very cool view.

With our flight leaving after dinner, we make one last journey to Malibu, first to check out Hotel June—a recently refurbished mid-century motel with a focus on West Coast surf culture. Then we stop for a walk in the sand and to dip our toes in the brisk waters of the Pacific at Malibu Lagoon State Beach.

On the ride back to LAX for our red-eye home, I think about how in many ways it’s been a whirlwind of a trip—catching rides to neighborhoods and landmarks all around LA, plus a little shopping and street tacos (at Platform in Culver City), a delicious breakfast at Gjelina and peek at the canals in Venice, and a couple of walks on the beach.

It’s a West Coast ramble that’s expanded my perspective on this essence of California living—to have as many connections to the outside as possible. Already, I’m mulling over where I can add more windows and doors, gardens and patios, places for dinners under the sky. Maybe Brad Pitt feels the same.

Learn more about getting around L.A. with a taste of SoCal style