Glimpse through the layered history of the city as well as the lives and livelihoods of merchants and tradesmen, mariners and artisans, immigrants and enslaved people

(Inset) St. Michael’s Alley, image taken in 1937 by architectural photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston for the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South

ST. MICHAEL’S ALLEY

Running between Meeting and Church streets and named after the Episcopal church on the alley’s northern side, this slim byway was originally merely an extension of Elliott Street. Narrow and sequestered, it was a favored duelling site. One of the more well-known duels occurred in 1786, when one combatant, mortally wounded, later died in the house on the Meeting Street end that today serves as St. Michael’s rectory. Midway down the alley stands the imposing brown-stuccoed former law office of outspoken Unionist James Petigru, who famously stated after secession in 1860 that “South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large for an insane asylum.” The circa-1848 structure, designed by E. B. White, was one of Susan Pringle Frost’s early historic preservation efforts in the 1900s. The house at No. 9 was built in 1913 by DuBose Heyward, whose novel, Porgy, was later made into the opera Porgy and Bess. The beautiful wrought iron “Cross & Egret” gate at No. 2 was designed by renowned Charleston ironworker, the late Philip Simmons.

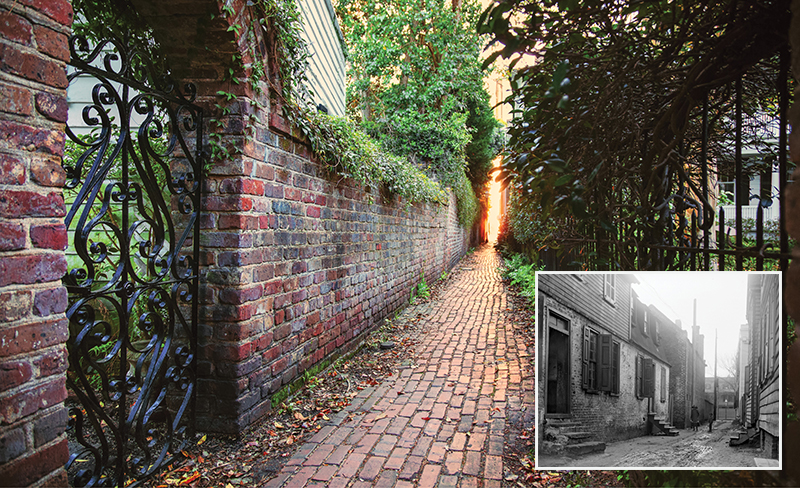

(Inset) Stoll’s Alley, circa 1880

STOLL’S ALLEY

The word “mystique” comes to mind when describing this postcard-perfect alley between East Bay and Church streets, just above Water Street. Originally known as “Pilot’s Alley,” ostensibly because early harbor pilots traversed this path to reach their boats, it later was named for blacksmith Justinus Stoll, who built the house at No. 7 around 1745. The alley is unusual in that it has two drastically contrasting ends: the Church Street entrance is much wider, with a spacious, cobblestoned colonial feel, and narrows toward East Bay, where it condenses to a five-foot-wide, brick-paved corridor flanked to the south by a grand East Bay mansion and to the north by a high brick wall. The alley is also notably home to five Philip Simmons wrought iron gates—some of his earliest commissions. Between 1919 and 1938, Alida Canfield bought and restored the decaying brick and wood slums at Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10, and her descendents lived at No. 5 until late in the century.

(Inset) Philadelphia Alley at the turn of the 20th century

PHILADELPHIA ALLEY

This quiet, picturesque passage between Queen and Cumberland streets was known as “Cow Alley” even into the 20th century, the nickname possibly derived from its use by early settlers to drive their cows to pasture or to market. In the 1740s, it was known as “Kinloch’s Court” for Scottish merchant Francis Kinloch, who built several residences for himself and his family here. In 1811, Charleston City Council renamed it “Philadelphia Street,” most likely in recognition of a history of mutual aid the two cities gave one another, including the kindness shown to South Carolina’s Revolutionary War patriots sequestered in Philadelphia after the British took Charleston. Legend holds that the alley was a popular place for duels, including one in which General William Moultrie is said to have fought by sword. The brick wall on the lane’s western side flanks St. Philip’s churchyard. The eastern side traditionally held warehouses, tenements, and small residences. By the 20th century, the lane had fallen into such squalor that a 1935 News & Courier article reported that some Philadelphians requested their city’s name be removed. In 2006, the City of Charleston restored and landscaped the lane, now officially “Philadelphia Alley,” resulting in its present shaded beauty.

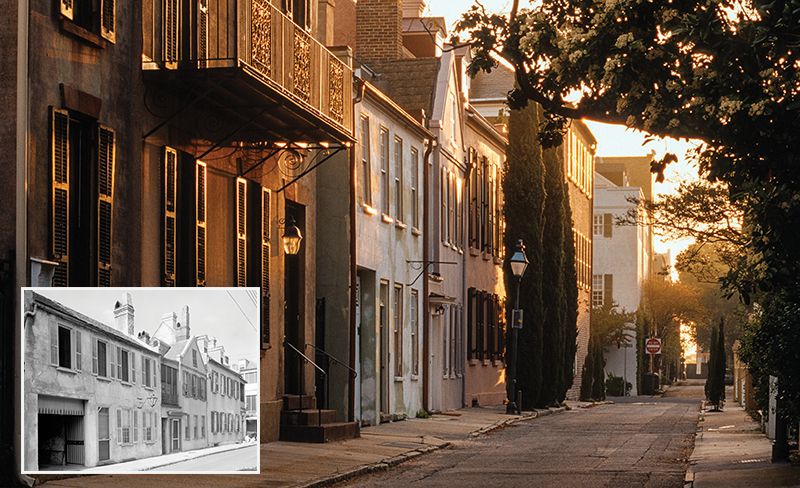

(Inset) Bdon’s Alley looking north to Elliott Street, circa 1920

BEDON’S ALLEY

Located between Elliott and Tradd streets, just a half-block off East Bay, this once bustling area hearkens back to the city’s beginnings with its vibrant mixture of chandleries, counting houses, and mercantile establishments. Originally called “Middle Lane,” by the 1730s it had taken the name of merchant George Bedon, son of Englishman George Bedon (Beadon) and his wife, Elizabeth, who arrived with the first fleet in 1670 and held original land grants. The alley is testimony to Charleston’s ability to rebuild after catastrophe, including severe damage from the fires of 1740 and 1778—the latter alone claiming 15 buildings on the alley. The prestigious St. Cecilia Society is said to have been founded in the house at No. 5. The small brick structures on its east side once served as outbuildings for East Bay’s Rainbow Row. Today, the alley’s former warehouses and shops have been impeccably restored as private homes in the Colonial Revival style.

(Inset) Longitude Lane looking east toward East Bay Street, circa 1900; the lamppost in the center remains to this day.

LONGITUDE LANE

Meandering down this 10-foot wide cobblestone connector between Church and East Bay streets is like strolling into Charles Towne’s earliest beginnings. Governor Thomas Smith owned property here in 1694, and there is evidence of rice having been planted between the lane and Tradd Street in that time period. By the early 1700s, the lane was known as “Jenkins Alley” for Edisto Island planter John Jenkins, whose Church Street residence abutted it. In the 1760s, it was renamed “Longitude Lane” (unusual in that longitude runs north-south and the lane runs east-west), likely a nod to the town’s bustling shipping trade and the commercial wharves then right across the street. Merchant George Bedon had a store at the foot of the alley on East Bay, and Nathaniel Russell sold his wares (sugar, imported wines, and rum) here as well in the late 1700s. In 1853, when a commercial cotton press (a facility compressing cotton into bales) was built here, a Revolutionary War cannon was unearthed, which residents placed in the center of the lane to deter noisy drays hauling cotton to the press. Beautified in the 1930s with added flagstone and cobblestone paving, today the residential lane remains remarkably unchanged.

PRICE’S ALLEY

It may be hard to imagine, but this short, rather elegant residential lane between King and Meeting streets just below Tradd was once swampy marshland. One of the earliest landfill projects in the city’s history, it originally marked the headwaters of Vanderhorst Creek, today’s aptly named Water Street. Once known as “Sommers Lane” for landowner Humphrey Sommers, it was renamed after Hopkins Price bought the property in 1749, agreeing to the stipulation that he keep “a good and sufficient Road causeway” through the lot. Price owned a tannery here, one of the many varied uses of this alley over time. Beyond the wall flanking the north side of the lane is the grand home built by wealthy merchant Nathaniel Russell; the lane itself became home to Irish immigrants and African American tradesmen. In 1783, butcher Leander Fairchild, a free man of color, bought land here and built a home for his family. The property remained in the hands of Fairchild’s descendants for more than a century.

(Inset) East Bay at Lodge Alley at the turn of the 20th century

LODGE ALLEY

In the heart of the French Quarter, this one-block lane between East Bay and State streets is one of the city’s oldest thoroughfares. It was first known as “Simmons Alley,” named for John Simmons, one of the original New England Congregationalists who settled the town of Dorchester in the 1690s and later owned land on the alley’s south side. Given its proximity to the wharves, the alley attracted a mix of commercial and residential uses, particularly boarding houses, where mariners and ships tradesmen could find affordable lodging. In the mid-1700s, tutors and “writing masters” taught school here, and in 1773, when the Society of Freemasons turned the former school building into the Marine Lodge, the name changed to its current moniker. By the 20th century, the alley was predominantly used for warehousing, and by the 1980s, many of the buildings were in disrepair and demolished. Today, condominiums and the Lodge Alley Inn carry on its lodging legacy.

ROPEMAKER’S LANE

“Rope Lane,” as this quaint alleyway near St. Michael’s Church was originally known, is entwined with a history true to its name. This small lane off Meeting Street between Tradd and St. Michael’s Alley was the site of Charles Snetter’s rope manufactory in the late 1700s and early 1800s. At 245 feet long and only 10 feet wide, it was sufficient length for a rope walk, i.e. a place to lay out, “walk,” and intertwine the cords of hemp used to ensure the stability required for the ropes made for sailing vessels. Snetter also manufactured other products at his Rope Walk, including bed and sacking cord, cotton lines for cast nets and seines, sewing twine, shoe thread, and even doctors’ “tow,” the thread used for stitching wounds.

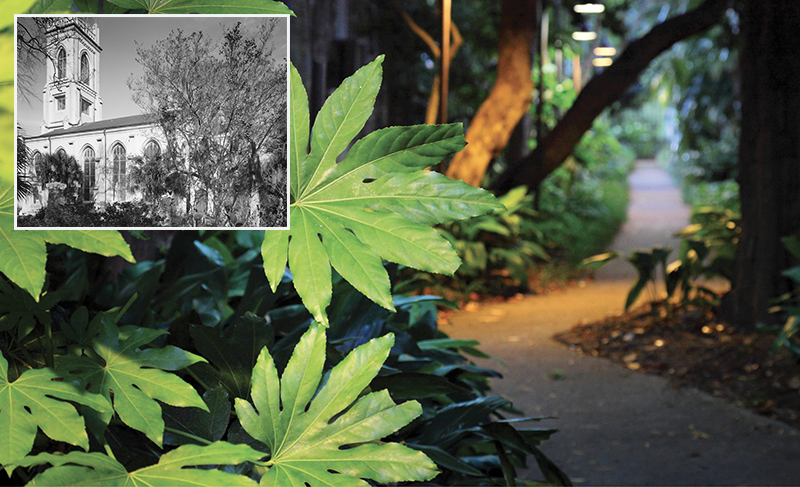

(Inset) Unitarian Church, 6 Archdale Street

UNITARIAN GATEWAY WALK

A lush oasis of verdant wildness right off busy King Street, this gem of an alleyway is a secret garden of sensual delight blooming alongside centuries-old gravestones. Connecting King and Archdale streets, this enchanting walkway winds through the churchyard of the oldest Unitarian Church (circa 1772) in the South, and the second oldest sanctuary in Charleston. This section of the longer Gateway Walk, designed by landscape architect Loutrel Briggs and the Garden Club of Charleston in 1930, extends from Archdale Street through the Gibbes Museum courtyard and down to Philadelphia Alley. The entrance off King Street is bordered with ferns and shade plantings traditionally found in a Charleston garden; approaching the churchyard, native flora grows and blossoms willy-nilly—its less manicured state reflecting the church’s beliefs about the web of life. When a portion of the wall on Archdale Street was removed to provide wheelchair access, the original bricks were repurposed for a memorial honoring the enslaved brickmakers who helped construct the church, featuring an African Sankofi symbol of a bird looking backward, meaning, “learning from the past in order to move forward.”

UNITY ALLEY

Once even narrower than it is today, this brick and Belgian block-lined passage between East Bay and State streets was widened in 1810. The area was home to merchants, tradesmen, and artisans in the late 1700s, including African American cabinetmaker John Gough. At No. 2 was Edward McCrady’s Tavern and Long Room, where President George Washington was lavishly entertained in 1791 at a banquet hosted by the Charleston branch of the Society of the Cincinnati. McCrady, whose original tavern was around the corner on East Bay, began purchasing surrounding property in the late 1770s and opened the Long Room on the second floor, with an entrance on the alley and horse stalls on the ground floor. Named for the room’s narrow length and extended dining table, the Long Room catered to upper-class Charlestonians who also enjoyed plays and musicals presented on a stage at one end of the space. After McCrady’s death in 1801, it became Eude’s Tavern, then the French Coffee House. In the early 1900s, the building served as a print shop, and in 1982, was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In the 1980s, it was renovated into McCrady’s Restaurant, which closed in April 2020, a historic tavern felled by a modern pandemic.

View more photos of Secret Alleyways & Lanes in Charleston

Photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston, courtesy of the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division; by Franklin Frost Sams, courtesy of Historic Charleston Foundation; by Arnold Genthe, courtesy of the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division; courtesy of the Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress