Meet the master of atmosphere and light before her City Gallery exhibit this month

Outside Linda Fantuzzo’s Bull Street studio, students zip by on skateboards. Professorial types stroll past on their way to office hours. Across the street, the stately Blacklock House, an imposing brick Adamesque structure that houses the College of Charleston’s alumni office, catches some of the rising morning light, casting timeworn shadows as it has since 1800. “It’s really lovely to work here, to be around the youthful energy of the college,” says Fantuzzo, who has turned the first floor of this circa-1880 wood frame beauty into her artist’s lair.

A vase of yellow tulips graces the mantel, stems of sunny cheer taking the edge off the late autumn chill. Classical music plays as sunlight dapples through the big windows. Fantuzzo’s studio is alive with creative wattage—whimsical assemblages of photos, books, paintings, and whatnots congregate on various surfaces. There’s art pretty much everywhere, tucked into nooks in closets and a warren of storage rooms. “I need lots of stuff around me—it fuels ideas for new work,” says the veteran Charleston artist, who brings her own energy to the Bull Street mix as well as a tireless compulsion to see things anew.

Fantuzzo shows up here daily, crossing the bridge from her home in Mount Pleasant and gets to work. “The more you work, the more you want to work, because the last painting often inspires the next,” she says. And her energy and focus is full throttle as she’s finishing 10 new pieces that will be part of “Penumbra,” her solo exhibition which opens at the City Gallery at Waterfront Park mid-month.

It won’t be the first time Fantuzzo has shown at City Gallery—her work has hung there several times, including “Contemporary Charleston,” the space’s inaugural show in 2003, along with her artistic mentor and friend, the late Manning Williams, and College of Charleston studio art teacher Jon Michel. Fast-forward 16 years, and Fantuzzo is still fresh, still contemporary, still pushing boundaries.

No longer the new kid “from off” who landed here in 1974, after graduating from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, she’s well-established with pieces in the Gibbes Museum of Art (which held her first solo exhibition in 1992), the college’s Addlestone Library, and the Greenville Museum of Art, as well as numerous private collections. Fantuzzo’s moody landscapes and abstract explorations of light, shadow, and architecture, as well as her still lifes, have had considerable staying power in an evolving Charleston art scene. This exhibit demonstrates her interest in evolving right along with it—by opening new doors and finding unexpected pathways and portals.

Beauty in Ruin: Fantuzzo at work in her light-filled studio, where all manner of art and artifacts (right) inspire her.

Atmosphere & Light

The front wall of the historical home that houses Fantuzzo’s studio is swallowed by a huge horizontal canvas—paper actually—on which Fantuzzo is applying sepia-toned oils with a dry-brush technique. The effect is wispy and ethereal, thanks to quick flicks of her wrist. To bring more light into the composition, she rubs the paint with a gob of kneading eraser—the artist’s version of the delete button. “Atmosphere and light are essential to my imagery, no matter the subject.” says Fantuzzo, an Endicott, New York, native who loved art early on, dabbling with her first set of paints and brushes at age 12.

This work in progress started as a vast swath of white, with hash marks of rough brush strokes along the right-hand side. But even so, you can see where Fantuzzo is going, with clues from the large, completed dry-brush painting that hangs vertically on the adjacent wall, an eerie, twilight image of a ruin—a shape punctuating an obtuse landscape of light. Watching her work is almost like watching a negative develop—back in the Polaroid Instamatic days. “This has a different energy; it’s immediate and quick, almost stream of consciousness,” Fantuzzo says, demonstrating her dry-brush technique. “I always crash and burn after a show, and dry brush is my go-to method of beginning anew. Working monochromatically is less demanding than working in color, which requires a great many decisions,” she explains.

The just-finished show she refers to was the first unveiling of “Penumbra,” which debuted at the Greenville Museum of Art in September. In fact, it was the museum’s curator Chesnee Klein who sparked the idea for this new series. On a visit to Fantuzzo’s studio, Klein saw a piece from an earlier series titled “Oblique Signs,” works that explored sites of decay, places often overlooked and on the periphery. “I want to find the beauty in ruin,” Fantuzzo says.

Similarly, the artist had recently completed a series exploring portraiture that grew out her fascination with mug shots, particularly of those charged with crimes “who often exist on the periphery, at the margins of society,” she says. She painted 35 portraits for “The Accused,” which earned Fantuzzo a South Carolina Arts Fellowship in 2017. But Klein was drawn to the artist’s almost mythic landscape images and inquired if she had more work in that vein that might become a museum show. “I said that I did not, but I’d like to expand the topic and create more,” says Fantuzzo. “That was two and a half years ago, so I just put my head down and did it.”

Well into her fourth decade as an artist, Fantuzzo has mastered “putting her head down” and working hard, but it’s work she relishes. “I have always been enamored of art. I treasure my art books, which are so vital when living far from the grand museums of the Northeast. I especially love the act of painting, perhaps even more than the end product,” explains Fantuzzo, who is equally at home with her French easel in the field painting plein-air as she is in the studio. Architecture is a recurring motif, as is painting a mini-painting within the painting—“fiction within a fiction,” she calls it—in her still lifes.

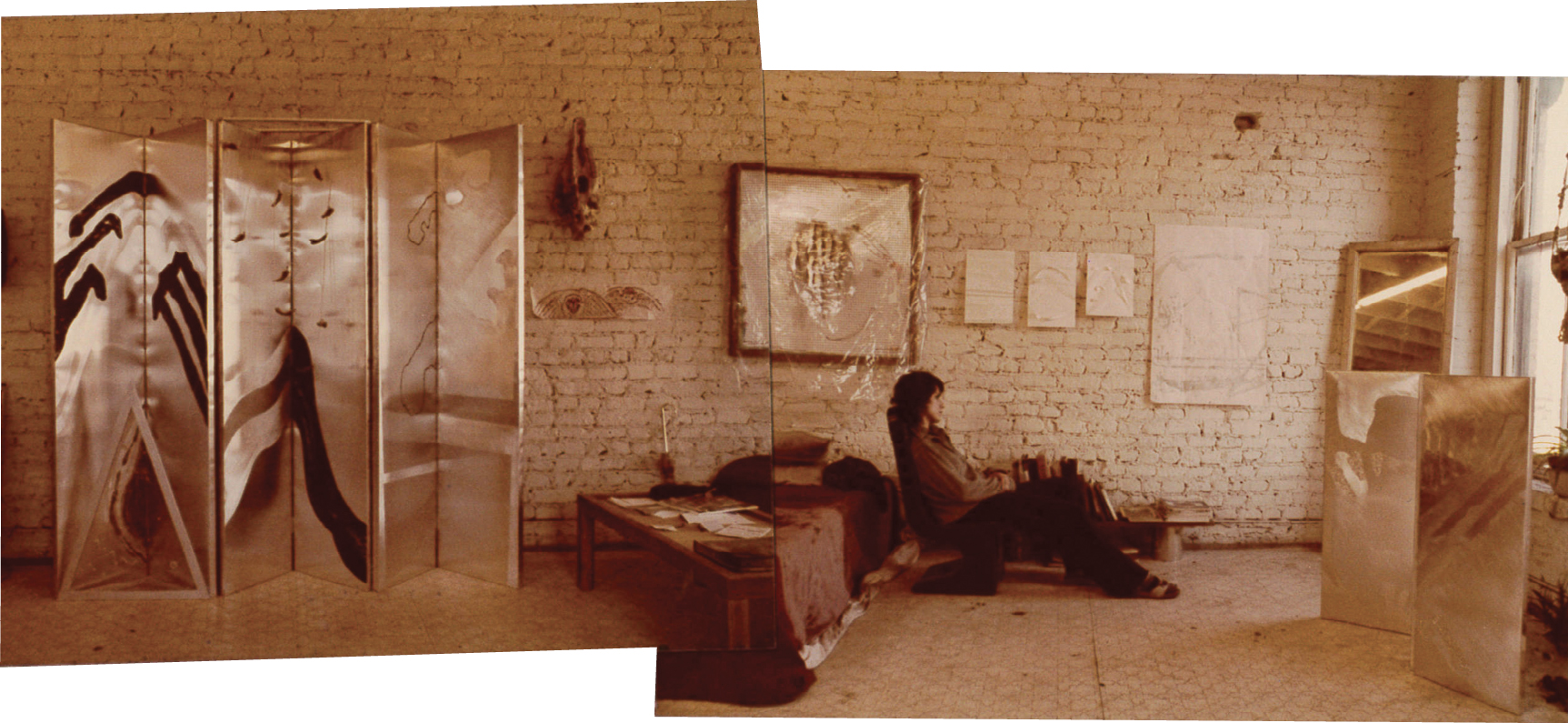

Early Work: In addition to painting, Fantuzzo was working in metals—such as the assemblages on display in her Cumberland Street studio—when she arrived in Charleston in the 1970s.

“Her output is phenomenal. She can paint circles around me,” says colleague and former studio mate Kristi Ryba, one of many local artists who hold Fantuzzo in high regard. “Linda’s surfaces are beautiful and full of painterly atmosphere, whether a still life or landscape.”

Mary Walker is another longtime friend who also once shared a studio with Fantuzzo, and the two often meet to critique each other’s work and bounce ideas off one another. “Coming from a bigger city like Philadelphia, there was always a sense of competition. In Charleston, it’s small, and from my earliest days here, we all encouraged one another. It was a positive atmosphere in which to grow,” says Fantuzzo, who lived and studied in Philadelphia before meeting her husband, Ed Warmuth, one summer in New Jersey.

After art school, she and Warmuth, a housebuilder, embarked on several months of coast-to-coast travels, which included a pit stop in Charleston to visit Manning Williams, a friend of Fantuzzo’s from the Academy of Fine Arts, and his wife, Barbara. The Williamses invited the couple for dinner, and Warmuth and Barbara immediately hit it off and became the best of friends. After making it to California, Fantuzzo and Warmuth felt drawn back to Charleston. “When we first visited, Manning and Barbara lived on Tradd Street. Manning knew everyone, so he helped us find a second-floor apartment on Hasell. The first floor was also available, and he and Barbara decided to take it. We shared meals and often entertained together; they became our family in Charleston,” she says.

Manning Williams was more than a friend to Fantuzzo; he was her colleague and mentor who opened doors for her in the nascent art community. A professor at the College of Charleston, he and William Halsey were the giants of the city’s contemporary art scene. “Manning was highly figurative and rendered things to the Nth degree; if he was painting a peach, he wanted to paint the fuzz on the peach. I was working nonobjectively. Though I came from a classical school, I worked abstractly for many years, at first doing assemblages from metals. People in Charleston hadn’t seen anything like it. Manning would learn from how I would compose, and I would learn just from his sheer passion for art, history, and knowledge of how to work. He taught me what a working art studio looked like,” says Fantuzzo, who in the early years worked a day job painting houses with Williams’s company, where she earned the nickname “Linda Winda” for her wicked speed and accuracy in cutting the sharp edges around windows.

She and Williams, who died in 2012, were featured in a two-person show at the Gibbes in 2004, and their work appeared together in other exhibits as well, including a 2002 Piccolo Spoleto project of large outdoor works installed on buildings and landmarks called “Larger Than Life: A Second Story Show,” curated by Fantuzzo. “Manning was the person I asked to critique my work before exhibiting it, I always trusted his eye,” says Fantuzzo.

His legacy is still shaping her outlook as she helps Barbara catalog, preserve, or place all of his paintings. “Dealing with Manning’s body of work has been a real eye-opener,” she says. “To be a prolific artist, one’s work accumulates, and what to do with all of it can be a dilemma,” says Fantuzzo, who plans to shift toward producing smaller scale paintings. In addition to being easier to store, “I like that they’re more spontaneous,” she says. “You don’t overwork a small painting, and what I do with a wrist movement looks big on a little painting. The quickness and freshness of it is pretty wonderful.”

Fantuzzo’s work is known for its painterly, almost mystical quality, whether in abstract landscapes or architectural themes. (Clockwise from top) Transitions (acrylic on canvas, 40 x 40 inches, 2019), Stairs at the Fort (acrylic on birch panel, 12 x 12 inches, 2014), Halation (acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 inches, 2018), and Mythic Realm (acrylic on birch panel, 40 x 40 inches, 2018).

A Way In

The “Penumbra” works, however, are of varying size and medium. Some are more traditional acrylics and some dry brush, but each is an invitation, imploring the eye toward light, toward an opening. “Ladders, windows, and doorways are a recurring motif,” she explains. And though Fantuzzo says she has never been a highly narrative painter and resists any political interpretation of her work, she “wanted a device to refer to a way out of, or sometimes into, a new space. “The news delivers information 24/7 about natural disasters, unemployment, homelessness, people migrating in search of a better life—so many people living in a state of insecurity. This is a constant of the human existence, and at some point, we all experience this. I looked for ways to explore that idea,” she says.

The show includes an additional entry point, if you will, spurring further interpretation and imagination, thanks to Fantuzzo’s collaboration with the poets of the Long Table, a group led by her friends Richard Garcia and Katherine Williams. Fantuzzo invited them to meet in her studio and create poems inspired by the “Penumbra” works. “The landscapes Linda chose—sky, ladders, water, walls, earth, stairs, doors, gates, windows—are what poets call ‘deep image’—especially resonant, fertile, evocative words that start generating lines of poetry almost immediately,” says Katherine Williams. “Then we have Linda’s marvelous, loose brushwork, vivid color combinations, and contrasting shadow and light, all setting a dreamlike stage for imaginative play.”

According to Mark Sloan, director and chief curator of the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art and a longtime admirer of Fantuzzo’s paintings, “Linda is one of those rare artists whose work is capable of transporting the viewer to another time and place. Her technical virtuosity as a painter is formidable, and she has a particular gift in representing light as a tangible presence in her work.”

Transporting the viewer is exactly what Fantuzzo hopes “Penumbra” achieves, whether via images evoking entry or escape, impermanence and transition, or through the multi-layered portals where poetry and painting overlap, creating openings within openings. The invitation to broaden one’s awareness and consider other realities, other interpretations, is what excites her as an artist and what inspired this particular collection of work. “I think that’s what artists have always been here for,” she says, “to point things out.”

SEE THE EXHIBITION

“Linda Fantuzzo: Penumbra” (January 18 to March 2)

The City Gallery at Waterfront Park features 50 of Fantuzzo’s paintings, drawings, and monotypes, accompanied by poems from the Long Table poets.

Opening reception: January 17, 5-7 p.m. City Gallery at Waterfront Park, 34 Prioleau St., citygalleryatwaterfrontpark.com

Photographs by (paintings) Keller James & (9) courtesy of Linda Fantuzzo