The Charleston Profile

Driving down Savannah Highway, past Ravenel and headed toward Beaufort, Savannah, or really anywhere south of Charleston, there’s an “oh wow” moment. Suddenly the road-framing pines and scrub oaks fall behind, and the horizon breaks open. Your eyes readjust, shifting from monotonous two-lane roadway to a bright vastness of salt marsh and sky. A few bleached and bare trees—“ramparts,” they’re called—stand as sculptural sentinels on the left side, signaling that you’ve arrived at the mouth of the ACE Basin, a 350,000-acre bowl where three rivers spill into the ocean, forming the largest undeveloped swath on the East Coast. Beyond the ramparts, a green expanse of spartina, occasionally dotted by herons and egrets, stretches as far as the eye can see.

It’s like entering a new dimension—that of pristine wildness. A primordial and immense estuarine prairie, it takes your breath away. Especially if you happen to be a little girl who has grown up in Manhattan’s concrete jungle, riding subways and pounding the pavement on the way to school, to gymnastics lessons, to museums.

“It was like encountering an other-worldly, almost mythical landscape,” says Ceara Donnelley, who, with her parents and four sisters, would “decamp” from their Upper West Side brownstone, hop the train to Yemassee, and spend Thanksgiving week with her grandparents Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley of Chicago. The devoted conservationists had built a hunting retreat at Ashepoo in the late 1960s and played a pivotal role in protecting the ACE Basin. (The Donnelley Wildlife Management Area in Green Pond, where the public can explore this coastal plain refuge, is named in their honor.) “It was my favorite week of the year. I’d go from being a city girl to being enveloped by a world of prehistoric alligators, armadillos, clouds of ducks, the smell of pluff mud, lots of dogs, and long-lost cousins,” Donnelley says of those formative memories.

Family Ties

Family, place, tradition. These three strands are intricately braided through Ceara Donnelley’s life, much like the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto rivers intertwine to create the ACE Basin. The imprint of that annual week of salty Lowcountry immersion with the formal meal rituals and hunting rhythms has sunk pluff mud-deep into her being. Today, she lives in downtown Charleston, relishing her proximity (45 minutes away) to that special retreat. “My grandparents also lived out their civic ethics at Ashepoo. There was always a sense that it was more than just a nice house and pretty place, but the real embodiment of our family’s identity,” says Donnelley, a graduate of Yale University and Yale Law School. Likewise her father, Strachan Donnelley—a philosopher and philanthropist who founded the Center for Humans and Nature—developed deep ties to Ashepoo and the Lowcountry, rooting much of his environmental ethic here. “This landscape was transportive to him,” says his daughter.

This sense of family identity and its grounding in place have been North Stars for Ceara. Her grandfather was chairman and president of R.R. Donnelley & Sons Co., and the third generation of Donnelleys to lead the Chicago-based commercial printing and publishing giant, founded in 1864. The company printed telephone directories, the Montgomery Ward and Sears & Roebuck catalogs, the Encyclopedia Britannica, Life and Time magazines, and was the official printer for the famous 1933 Chicago Exposition, among other significant contracts. In 1952, he and his wife established the Gaylord & Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, which continues to be a major funder of arts and land conservation in the Lowcountry and the Chicago region.

“My grandfather was an incredible leader and CEO, beloved by his colleagues and friends. I still encounter people here who knew him and share glowing memories,” his granddaughter recalls. “He had a strong presence. When we were with him, you made sure you sat up straight.”

Her well-traveled grandparents loved the outdoors, the arts, and hosting their many friends, especially at Ashepoo. “At the time, this place felt undiscovered, as if they’d found an untapped secret,” says Ceara, and this furtiveness further enchanted them and reinforced their desire to protect the land from development. In terms of the house itself, it reflected her grandmother’s unique and highly personal aesthetic, “a style that was curated over time and designed for joy and contentment,” and one that remains intact today. “It’s kind of a time capsule,” Donnelley says, of the Lowcountry home and landscape that her extended family still cherishes.

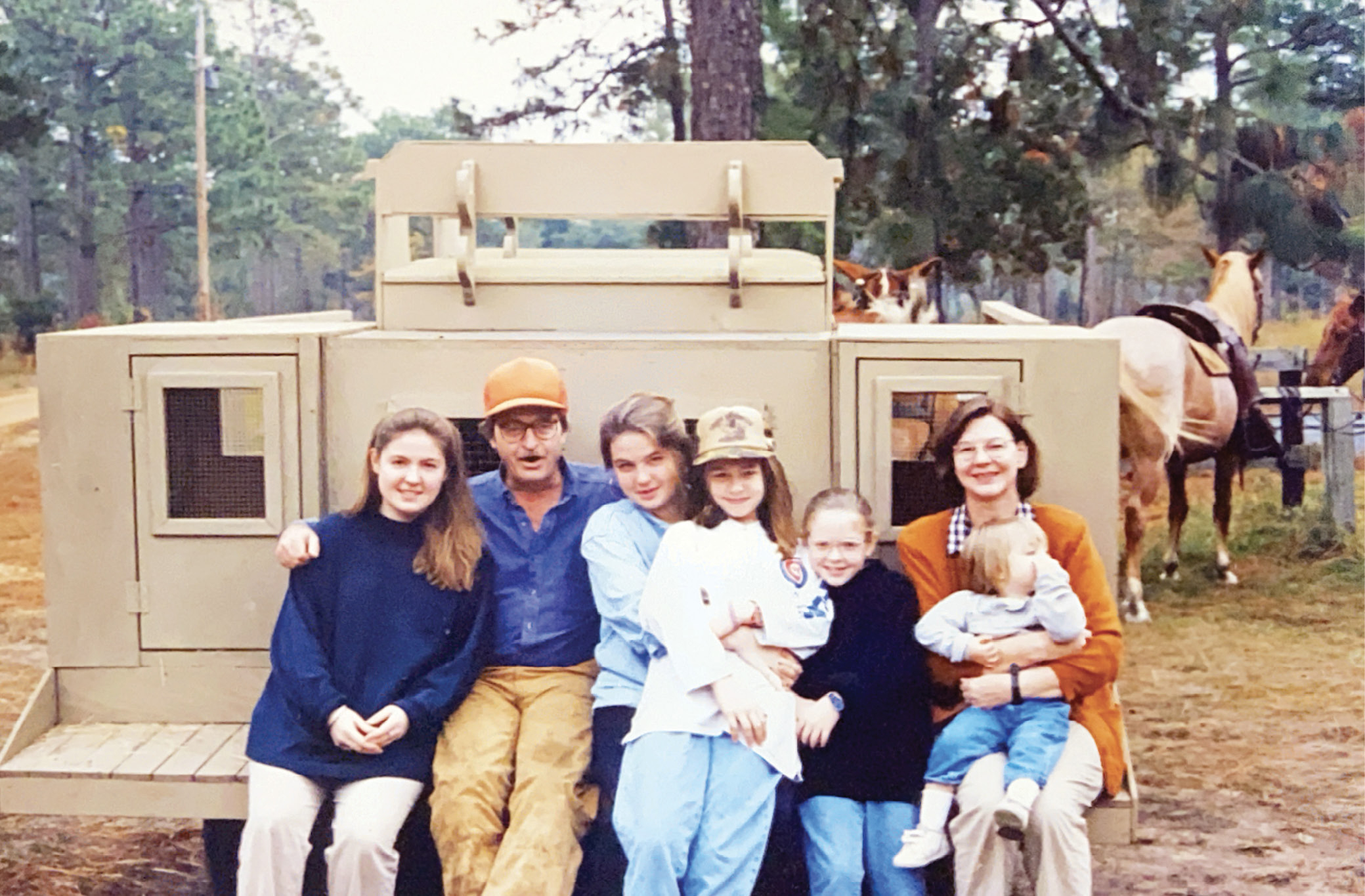

The Strachan Donnelley family on the Ashepoo mule wagon, circa 1989: (from left) Naomi, dad Strachan, Inanna, Aidan, Ceara, mom Vivian, and Tegan

Migrating South

Despite such formative time spent in South Carolina, Ceara, the fourth of five Donnelley sisters, hadn’t considered that this might be a place where one actually lived full time. On their annual trips, her family stayed at Ashepoo and never ventured into town, “so I didn’t know Charleston well, and certainly hadn’t envisioned it as a place to raise kids, work, and do the daily grind,” she adds. But since 2012, Donnelley has been doing just that, thus building on her family’s multigenerational ties to the area, in her own way. Rather than being based in the ACE Basin, for example, she has renovated a historical home on East Bay Street, albeit one with ties to her family’s conservation ethic (she bought it from the Lane family, fellow conservationists who worked with her grandparents and father on protecting the ACE Basin). Across the street on Adger’s Wharf, she has launched an eponymous interior design studio, specializing in residential projects.

The thought of leaving New York, however, wasn’t something Donnelley had considered until her father got sick and ultimately died of cancer in 2008—the year after she and Nate Berry were married at Ashepoo and the summer before her final year of law school. “His death upended everything, and I lost all attachment to ideas of what my life in New York would be like,” says Donnelley.

By virtue of spending time with her father throughout his illness, helping him organize his academic writing and philosophical reflections into a book, Frog Pond Philosophy (which was published posthumously and which Ceara edited), her priorities and perspectives began to shift. Having her first child before beginning work at a large corporate law firm also contributed. “I left after a year; it just wasn’t for me,” she says. Plus, she and Berry had gotten to know Charleston better while planning their South Carolina wedding, and they realized the city was, in fact, vibrant.

“I’d always heard no one actually lived downtown,” she says, so during visits here, she began peering into backyards looking for swing sets and kids’ bikes and happily found them. When they realized Berry’s conservation career with the Open Space Institute could advance here, the couple made the move with two young children—their son, Rafferty (Raff), was three at the time, and daughter, Hayes, just five months old. “We thought it might just be a temporary pit stop,” Donnelley says. But nine years later, here she is, having wasted no time becoming deeply involved in the community. Locally, Donnelley has served on the boards of Ashley Hall; the Charleston Library Society, where she co-hosted the Wide Angle Lunches lecture series; and the Coastal Conservation League, which she currently chairs. She also serves on the board of the Center for Humans and Nature, a think tank dedicated to the multidisciplinary exploration of how humans can responsibly and creatively relate to the natural world.

By Design

The move to Charleston has marked a period of growth and change for Donnelley. She and Berry are in the process of an amicable divorce, for one, and her mother, Vivian, an equally monumental force in Donnelley family life, died of cancer in 2018. “She put her all into raising five girls. She loved being a mother and creating a home, but she always wanted us to fly,” Ceara says of her mother, whose Midwestern Lutheran upbringing prized “intelligence and achievement.” Practicing law was a career choice that her mother, a voracious reader and trustee of the American Museum of Natural History,

applauded; her daughter’s decision to give that up, move to Charleston, and pursue interior design was, at least initially, less understood.

“But there was a moment when Mom, who had been staying with us for several weeks after recuperating from a fall, said, ‘You really thought of everything, didn’t you? You thought of everything in designing this for your family, and how you live in this house. I’ve lived my whole life fitting myself into places. It never occurred to your dad or me to make it fit us.’ That, to me, was her praise, her way of saying, ‘I get it,’” says Donnelley, a history lover who orchestrated a two-year renovation to her circa-1740 home, incorporating many pieces from her parents’ collections mixed with antiques and mid-century pieces found at auction, all amid bold colors and patterns.

“Design saved me when my dad was sick and in hospice. It allowed me to engage a different part of my brain, and I loved it,” says Donnelley, whose father was an avid collector and art lover and from whom she gets her aesthetic proclivities. She found the same solace and inspiration in design work during the months before her mom died.

Two weeks after her mother’s death, Donnelley signed the lease on her Charleston studio space, finally fully committing to her design business, for which she has since garnered national press. “I’ve realized that the project of adulthood is to interrogate the things you inherit and decide what you want to hold on to and what to release. Many of the raw materials and talents that I use in my [professional and volunteer] work I was given by my family, but I’m building on them in a way that’s completely new and different, and it’s thrilling,” she says.

Today, Donnelley enjoys quiet time at Ashepoo and busy family times, too, as her son and daughter explore the horse trails and old rice fields with their cousins, just as she did decades ago (right) with sister Aidan and cousin Mimi Wheeler, checking out the horses, circa 1986.

Environment Matters

Since launching her business, Donnelley has streamlined her board activities, channeling her energy and focus on the two organizations most closely aligned with her family’s legacy: the Coastal Conservation League and the Center for Humans and Nature. At the Center, now based on Donnelley family farmland outside of Chicago in Libertyville, Illinois, she works closely with president Brooke Hecht, offering strategic guidance to expand and deepen the nonprofit’s mission, including creating a series called “Questions for a Resilient Future.”

“I saw how deeply Ceara poured herself into the publishing of her father’s book. She’s an incredible thinker and writer, like her father, and she has deeply absorbed his wisdom for understanding how humans and nature interrelate,” says Hecht. “When I think about Ceara’s design work, I see it from the perspective of an ecologist. We need beauty in our lives. Trees create their own habitat; birds and animals build nests. She’s doing niche creation, too, drawing on the philosophical traditions and her life experiences in a creative, beautiful way. As her father might say, she’s participating in the frog pond of life.”

Similarly, in her role as board chair for the Coastal Conservation League during a time of institutional transition, Donnelley has been a steadying force. “She has a natural leadership style, a way of ensuring everyone feels heard and understood while still moving things forward. It’s an art,” says executive director Laura Cantral.

Cantral and Donnelley have led the board and staff through a time of reevaluating the 32-year-old organization’s mission and vision, “doing a gut check,” says Donnelley, “of who we are and what we do.” For the remainder of her term, she is committed to advancing the Conservation League’s ongoing work toward equity and inclusion, which includes efforts to diversify the board and staff, and a serious evaluation of the organization’s program work. “One of the Conservation League’s talking points is ‘quality of life,’ but the reality is that certain members of our population are disproportionately affected by bad policy decisions. We need to address that, and to have a clear lens for why the Conservation League decides to tackle certain projects and not others,” she says.

It’s complex work, and quite different from coordinating paint colors and fabric patterns, but it all comes down to enhancing and honoring place—the domestic and natural environments that we call home. Donnelley sees her work with the Center for Humans and Nature and the Conservation League as complementary: “The League is all activists and advocates, really smart people pursuing change and legislation on the ground, while the Center is all about the moral imperative argument, the why and the how, and how to articulate that. The idea is to give all the everyday doers working at the conservation leagues out there the intellectual space and tools to be more effective in speaking a values-based language,” she says, giving tangible expression to her father’s vision and hopes.

Strachan Donnelley was a Darwin fan, the son of ardent land lovers who saw beauty and found wisdom in species’ ability to change and evolve. No doubt, seeing his daughter evolve and carry forth so many aspects of the Donnelley family legacy in her own creative ways, by her own design, with her two children in their own chosen town, would make the “fly-fishing philosopher” a proud man.

“My life looks nothing like what I thought it would as a little girl, and I am grateful for that,” says Ceara. “These years in Charleston have taught me how to live on my own terms, to make meaning of beauty and loss and, most importantly, change.”