The home marries a historic-seeming exterior with modern interiors, while windows galore allow a flood of natural light

In June 1977, Lee Bell was playing guitar on a barge in the Cooper River. The Walterboro native had been hired to entertain diners at the Scarlett O’Hara restaurant, docked at the end of Charlotte Street. The occasion was the first year of the new arts extravaganza, Spoleto Festival USA. “I was working all week so I didn’t get to see anything but the finale at Middleton Place,” says Lee. But that was enough. He fell in love with the festival, returning the next year to work at the box office and almost every year after as an employee or patron. “There were some incredible performances,” he recalls. “The Nederlands Dans Theater, uMabatha, the Zulu dancers’ adaptation of Macbeth—amazing. And it continues every year. Spoleto has been pretty profound and unique in its selections.”

Although he left South Carolina and settled in Florida, where he enjoyed an illustrious career as director of the famed Kravis Center for the Performing Arts in West Palm Beach, Bell decided to retire to Charleston three years ago. The city’s charm had also captured the heart of his husband, Fotios Pantazis. “I’d come to Spoleto with Lee for the last 10 years and knew I could live here,” he says. “It’s an amazing town—very chic, very cosmopolitan.”

The couple set their criteria for their ideal home—a place with plenty of sunshine (Foti suffers from seasonal affective disorder) and a short walk to the beautiful sunsets on the Battery, as well as the many cultural hot spots of the city. But crucially, they didn’t want an historic home. “I lived in Boston for many years in an historic neighborhood, in an historic condominium,” says Foti. “The idea of rattling windows and crooked floors—all that ‘Old World charm’—just doesn’t work for me.”

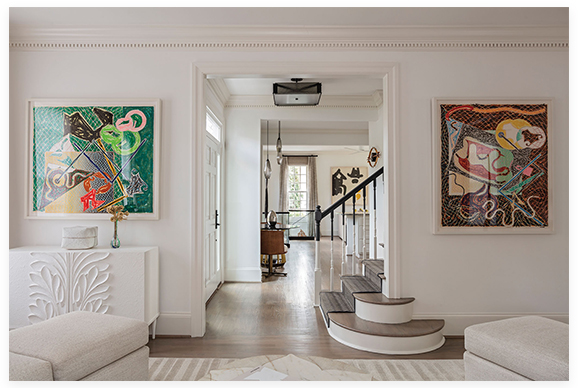

In the formal living room, two of three Frank Stella “Shards” lithographs sit atop two Dorothy Draper-inspired commodes from Baker Furniture.

While contemporary homes are few and far between on the cobbled streets South of Broad, Lee and Foti eventually found their unicorn in 2020. The 2,900-square-foot house was built in 1990 in the former garden of an older residence to its north. Elevated to protect it from flooding, the house has a two-car garage and is just blocks from the Battery. It also had something that Foti really wanted: a concrete wall.

“What sold it for me was that the fourth bedroom downstairs has a concrete wall—ideal for a gym,” says Lee, who saw the house before his husband. Foti, a former business consultant, had switched careers to become a medical exercise specialist and needed a gym in the home for his practice. The open floor plan—another anomaly among its historic neighbors—immediately appealed to Lee. Along with 36 windows, allowing sunshine to stream in throughout the day, it added up to perfection.

Despite the newer construction, the home was built in a classic style with traditional interiors. The couple wanted something more modern to complement their museum-worthy art collection and hired Mitch Brown, owner of David Mitchell Brown design firm in Palm Beach. They gave Brown, who had designed their previous home, free rein to choose the furnishings, light fixtures, and color palette, sending him photos of their art for context.

The result is a light, airy modern space, with a boho-chic feel. “We wanted to create a clean and modern design that would showcase art beautifully,” says Brown. “I chose furniture that would provide beautiful and unusual shapes and silhouettes that would provide interest but not overwhelm.” Most of the pieces correspond to the same period as the art collection.

When they moved in just over a year after closing, Brown surprised the couple with a reality-TV style reveal. “We never saw any of the work in progress,” says Foti. “And we loved it. It’s a personification of the Yiddish term beshert, ‘meant to be.’ When I walked in and saw the sofa and above it the Louise Nevelson piece that was a gift from our dear friend, Marjorie Fink, who had recently passed, I knew it was meant to be.”

(Left) A Hellman Chang table is flanked by swivel chairs from Baker Furniture. (right) Two features enticed Lee Bell and Fotios Pantazis to purchase this charming home for their retirement. First: behind its historic-seeming exterior lies a more modern construction—the house was built in 1990—with an open floor plan as an ideal canvas to showcase the couple’s stunning art collection. Second: windows galore allow natural light to flood the interior.

Structurally, nothing major needed to be done to the home. A few upgrades included new floors, removing a brick fireplace surround, and replacing a half wall down to the gym with a glass divider. At first, they considered a similar approach for the traditional wooden stair banister. “But Mitch suggested this two-tone look, which we love,” says Lee of the wood spindles painted graphite and off-white that are now a striking design element. Like the banister, the home’s design embraces the traditional feel of the architecture, while complementing its owners’ love of contemporary art and design.

Brown selected mid-century modern furnishings with a hint of Art Deco. The downstairs living area, encompassing a sitting room, dining room, kitchen, and lounge, is dominated by clean lines and geometric shapes. A white palette with black underpinnings and pops of color and pattern allows the couples’ art to be the star of the show, with the furnishings as occasional scene-stealing extras.

Two curved sofas in the living room surround a mid-century, marble and brass coffee table Brown discovered in a New York antiques store. “This was actually the jumping-off point for the home’s design,” says Brown. It sits in a focal point of the home, framed by three Frank Stella lithographs from the abstract American artist’s “Shards” series. The pure white of the sofas and the neutral tones of the drapes give the colorful artwork room to breathe.

A newly installed, signed print of Jasper Johns’s Land’s End leads from the adjoining dining room to the hallway into the kitchen. Here, a framed 1985 Spoleto poster, designed by Johns from his Land’s End work, adds a scintillating touch of artistic symbiosis. Around the corner, a small powder room tucked under the stairs hosts an original Salvador Dali sketch, the room adorned in a shimmering silver Philip Jeffries wallpaper, complete with a melting mirror homage.

Up the stairs lies something arguably even more special: an installation by local artist and longtime friend Paul Hitopoulos, commissioned for the stairwell. “We gave him free rein; we wanted something contemporary,” says Lee. Inner Elevation is a collection of plaster “bones” encased in handmade wooden boxes, each crafted from a single piece of wood, hand-splinted by Hitopoulos, who learned the woodworking technique for this piece. “I was so thrilled to be asked to do something,” says the artist, whose usual method generally involves ripping open walls and filling them with living materials like grass. “I figured they didn’t want to rip open their wall.”

A sculptural chandelier illuminates the installation, which leads up the stairs to one of Foti’s favorite pieces, Kevin Chadwick’s Cats Cradle. “This moves me more than anything in the house,” says Foti of the soulful piece depicting a Black boy playing cat’s cradle with a white cardinal perched on his hands. “It becomes more powerful over time.”

For Lee, Charleston itself has been a powerful draw, from his youth as a musician, living on Folly Beach in the ’80s through his fervent Spoleto attendance to today, coming full circle, once again calling the Holy City home and joining the festival’s board of directors.

“We love being a part of the fabric here and helping with the arts,” says Lee, of their patronage of Pure Theatre, the Gaillard Center, New Muse Concerts, and more. Foti has also joined We Are Family’s advisory board, a North Charleston nonprofit that provides life-saving and life-affirming services to LGBTQ youth.

Lee is thrilled with the cultural growth of the city and knows where it all began. “Spoleto started the revitalization of interest in Charleston and the growth of its cultural experiences,” he says. “It brought an excitement and an awareness, a change in perceptions of the audience to what’s out here, what’s possible.”