(White Point Gardens retains a nod to the moniker.) Colonists paved roads with shells and crushed them to make tabby for building houses and fortifications. Today, locals are still on intimate terms with the bivalve, but we’re betting you don’t know all of these tasty facts.

Thanks, guys:

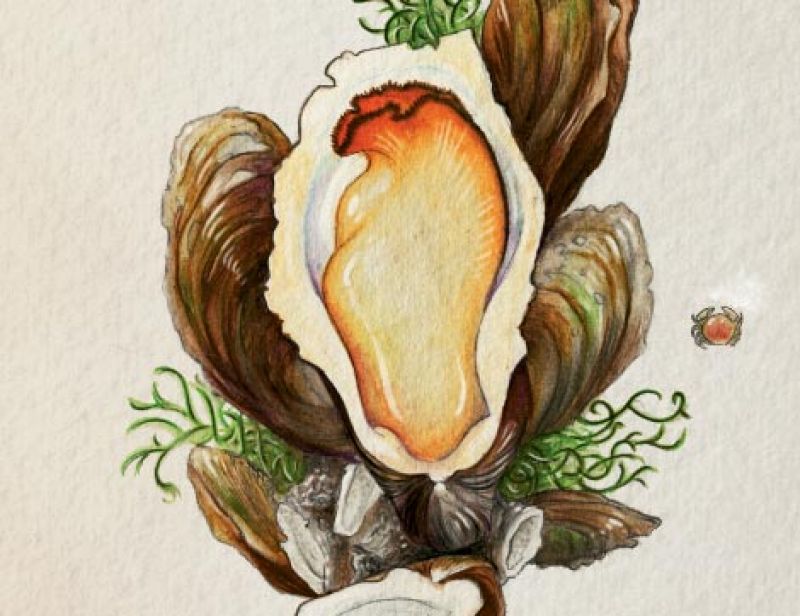

These filter feeders ingest plankton and algae by opening and closing their shells (hinged together by an extremely strong adductor muscle), flushing an astounding 50 gallons of sea water a day through their gills. This not only provides the oyster with nutrients but helps cleanse the habitat of harmful pollutants.

Sex & the Single Oyster:

In a spawning season, one oyster can eject as many as 100 million eggs into the water, but only a small percentage of them reach maturity. The eggs become larvae that attach to other oyster shells and grow quickly into small oysters called ”spats.”

Roasting ritual:

Oyster roasts have been popular since the days of the early coastal Indians, who used the razor-sharp shells as knives for tasks such as tanning animal hides. They also created shell rings, likely for ceremonial purposes, and the Lowcountry boasts two of the largest remaining—one at Fig Island near the mouth of the North Edisto River and the Great Sewee Shell Ring near Awendaw, some 225 feet in diameter.

And So To Bed:

The shells have an extremely high (95%) calcium carbonate makeup and secrete a substance that acts as an adhesive that bonds them together in tight clusters, forming colonies known as “beds.“ These colonies provide a habitat for other marine life, help prevent erosion, and create barriers against storm-driven seas.

Lucky Charm:

Also called a “pea crab,” this tiny soft-shelled crustacean (Pinnotheres ostreum) lives symbiotically in the oyster and is considered a delicacy by gourmands when found in a steamed bivalve. Some believe that discovering one brings good luck.

Local Flavor:

Lowcountry oysters grow in clusters—with young oysters piling atop older ones in intertidal areas of creeks and sounds that are left exposed by high tide.

For a brown oyster stew recipe by chef Robert Stehling of Hominy Grill, click here.