Then read about the Gibbes Museum of Art’s exhibition, “Something Terrible May Happen” displaying his work

The time is 1924; the setting, a moonlit garden on a plantation outside Charleston; the occasion, a meeting of the newly formed Society for the Preservation of Spirituals. Descendants of the plantation gentry are singing Gullah songs learned from the children of the enslaved. All is fine until, in the moonlight, something stark, white, and half-naked appears. Like a satyr from Greek mythology, the masked creature—seemingly half-man, half-beast—leaps forward to dance. When the creature tries to speak, haunting, malformed sounds come out.

“Who is that?” an aghast guest asks. The answer: Ned Jennings.

Soon the sky pales to morning. Later at the Charleston Museum, a young man in coat and tie bends over his dioramas—miniature scenes depicting ancient Greeks, Egyptians, and medieval men going about their daily routines. In coming decades, local children will peer at these displays, called “The Drama of Western Civilization.” The three-dimensional tableaux will be recalled with pleasure by thousands for years, but hardly a soul will remember the drama of their maker—the masked dancer and fantastically gifted but doomed Edward I.R. Jennings.

He was born in 1898 in Washington, DC, and moved to Charleston with his parents within a few weeks. His father would become postmaster of the city and an early developer of Folly Beach. Jennings attended Porter Military Academy and soon joined the “boys” that Laura Bragg, director of the Charleston Museum, would mentor over the years. (Many of Miss Bragg’s boys went on to become scientists, artists, and leaders in their fields.)

Bragg saw something special in the shy, handsome youngster, whose secret was revealed only when he opened his mouth to speak. He had a cleft palate, “a defect no surgery or time could ever repair,” wrote artist and author John Bennett, who also took Jennings under his wing. Even those friends who knew him were “obliged, time after time, to ask again what he had said, to understand the hollow, half-formed sounds he made instead of common speech.” This flaw built a strange barrier between Jennings and the rest of the world, and even as a teen, he took refuge in his drawings and dreams.

As a young man, he joined the Charleston Light Dragoons and saw action on the Mexican border as World War I broke out. Jennings tried to enlist in the military, but his cleft palate disqualified him, so he volunteered to be a medic and was stationed first in Upstate military camps, where he nursed young soldiers who responded warmly to him.

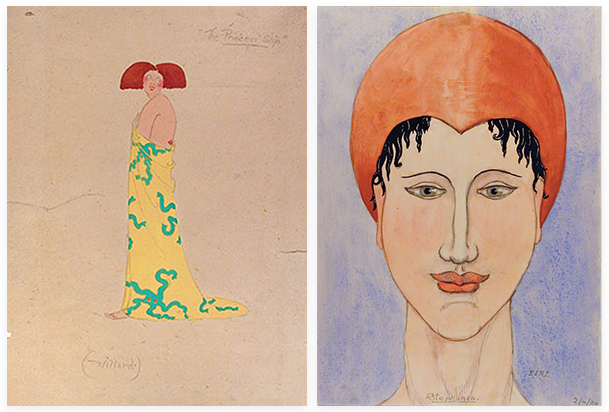

(Left) Stephania (watercolor on paper, 10 1/2 x 8 inches, 1920); (Right) Costume design for The Princess’ Slip (gouache on paper, 12 x 8 5/8 inches, 1922)

In the Shadows

“There are such a number of shapes and shadows in my mind that won’t take any shape,” Jennings told a friend as he grappled with his dreams and groped for happiness. He had wild mood swings. “Sometimes I should like to fly up, and up, and up! Up into the stars!” While at other times, “I feel like a thousand and one blue devils are inside….” He tried to express himself to others, but confessed, “I don’t know myself,” concluding sadly, “I have a lonely soul.”

In 1919, while stationed in France, Jennings was both repelled and entranced by the beauty and horror of the battlefields—extremes that would later become the poles of his imagination, warring for his “lonely soul.” Oftentimes, he envisioned demons, nymphs, and dryads, and while watching the countryside, he waited for Pan to appear. Instead the enemy showed; he was gassed, sent to England to recover, and soon thereafter returned to Charleston Images from Jennings’s dreams continued to obsess him. After a brief stint at the College of Charleston, he attended Columbia University in New York and earned an art degree, then left for a year to study drama, costume, and stage design at the drama department of Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute of Technology. The work, he wrote, was “chosen with the idea of giving me the knowledge to represent—either in painting or as a model—any place, period, or peoples from prehistoric time down to the present day.”

With these skills, Jennings was named curator of art at the Charleston Museum in 1925. There, he continued his dioramas on the march of civilization. Ironically, he could create any time, place, or setting from the past, but there was no place in the real world that truly fit Ned Jennings. While his cohorts at the museum and other artists in Charleston, such as Elizabeth O’Neill Verner and Alfred Hutty, were grounded in realism, creating iconic images of the city, Ned, a bit younger and wilder, drew fish in Marine Ballet, made horrifyingly grotesque masks out of papier-mâché, and painted mythological beasts, darkly veiled faces, and creatures no other human being had ever seen.

In 1926, he created The Show Box, a theatrical production he described as “a group of romantic and sparkling scenes woven into a tapestry of color, lights, music, and dancing” as a fundraiser for the Junior League. The program revealed his sense of humor, too. In a scene of bullfighters, the “last half of the bull,” according to the credits, was played by Jennings. He poured his heart and soul into the show, but it barely raised any money for the organization as Charlestonians didn’t know what to make of such weirdly beautiful fantasy.

The city was changing in these years; the old stately rhythms of the place, like those of a minuet or a quadrille, were at odds with the jazz syncopations of the “Charleston” being danced with abandon in the streets. Jennings was pulled between being a dutiful son and an artist untrammeled by convention. He left for Paris in 1927 to study privately with artists Mela Meuter and Walter Renee Fuerst, but then returned to Charleston again.

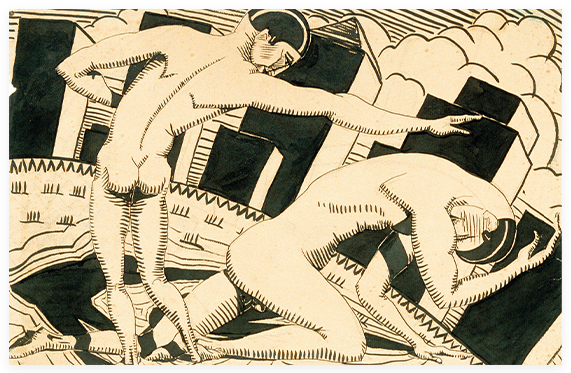

Two Figures (ink on paper, circa 1928)

Breaking Point

Jennings’s moods swirled as dramatically as the colors on his canvases, and he felt a sense of crisis upon reaching the age of 30. Miss Bragg, watching, would say that “she had never seen anyone work so long for so little.” Other artists were supporting themselves, but not Jennings. Even though he was an instructor at the Carolina Art Association, he made few sales of his works, which bore such titles as Man with a Blue Fan, Revolt of the Elements, and Dancer with a Whip, and depictions of destructive lovers such as Henry the VIII and Anne Boleyn.

Then in May 1929, something happened to Jennings. Bennett wrote that another young man had “made his home” with the artist, a circumstance that apparently made Jennings happy. Sadly, the fellow left abruptly. “Thus seemingly deserted by his last most intimate companion, Ned seemed bewildered and distracted,” noted Bennett, “wavering between new resolutions and new gatherings up of hope and plans.” The vacillation showed in dramatic new art pieces: Top of the World portrays a man dancing in precarious balance on the moon, while Lot’s Wife features a somber pillar of salt, the ultimate symbol of someone paralyzed by looking to the past.

Just as Jennings’s artwork varied wildly, so did his moods. One night, he seemed fine, noted Bennett; on another, there was “some small subtle difference.” With the next afternoon came “a stormy scene” between Jennings “and [his] ephemeral companion, thoroughly frightening the latter,” and later that night, “his conduct was irregular and extraordinary; wild, nervous, and disturbed; pacing around his room or going out to the little landing to stare silently at the stars.”

Friends couldn’t locate Jennings the next morning, and he wasn’t at his parents’ house on Tradd Street. They rushed to his studio at the Confederate Home between Broad and Chalmers, where the unlocked door stood open. Bennett wrote, “He was found there, 12 hours dead, about high noon, still sitting in his chair, a Bible opened in his lap, a Champagne bottle at his side, and a revolver brought from home, dropped from his hand: he had shot himself through the head. And with a strange, but most characteristic gesture of dramatic, stage-like artifice—bottle, weapon, and Bible arrayed into that tragic scene—had put an end to it all.” All around on the walls, the masks he had hidden behind to express what he could not say in words were a mute chorus to the tragedy of Ned Jennings, who died about a week shy of his 31st birthday.

A few days later, he was buried in Magnolia Cemetery, where Bennett said a prayer: “May the earth lie lightly on him.” There were a few shows of his work across the country over the years, but people were largely confused by his visions. Today, this lonely soul’s modernistic works still pierce us with their darkness and their light, their colors and their imagery. His half-formed shapes and half-finished work, unappreciated in his time, have become comprehensible to a modern audience. He has found us, those who can understand him, at last.

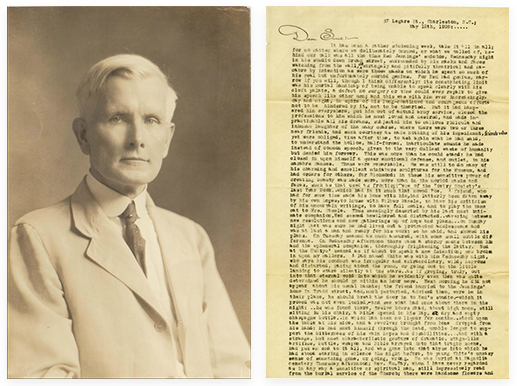

Author John Bennett, a leading figure of the Charleston Renaissance, wrote of Ned Jennings’s suicide in a letter to his daughter, Susan (right).

Author Harlan Greene on Ned Jennings’s tragic end

The letter in my hand was startling. “It has been a rather sickening week,” it began, “for no matter where we deliberately turned, or what we talked of, behind our talk was… Ned Jennings’s suicide, Wednesday night, in his studio down Broad Street, surrounded by his masks and faces watching from the wall.” ... >>READ MORE HERE

“Something Terrible May Happen: The Art of Aubrey Beardsley & Edward ‘Ned’ I.R. Jennings”

October 20–March 10

This new exhibit at the Gibbes Museum of Art explores queer influences on the Charleston Renaissance (1900-1940), a period of artistic awakening in the city that saw the publication of Debose Heyward’s Porgy, which inspired Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. By comparing works by famed British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley and artist Ned Jennings, the show establishes the significant impact of the British Aestheticism Movement (1860–1900)—which aimed to produce “art for art’s sake,” bucking the social conventions of Victorian culture—on Charleston. The exhibit will “shed a provocative new light on our understanding of the underpinnings of the Renaissance and examine the influence of queer culture and aesthetics more broadly,” says curator Chase Quinn. “Whether or not these artists identified as LGBTQ, there is much evidence to support that they were influenced by queer culture.” Gibbes Museum of Art, 135 Meeting St. Monday-Saturday,10 a.m.-5 p.m., Sunday, 1-5 p.m. $12-6. (843) 722-2706,

gibbesmuseum.org

“Queering the Renaissance”

November 15

In conjunction with the exhibit, “Something Terrible Will Happen,” award-winning author and historian Harlan Greene leads a special talk illuminating the unacknowledged LGBTQ presence in the arts in Charleston in the early 20th century. Gibbes Museum of Art, 135 Meeting St. Wednesday, 6-7 p.m. $30, $20 members, $15 student/faculty. (843) 722-2706, gibbesmuseum.org