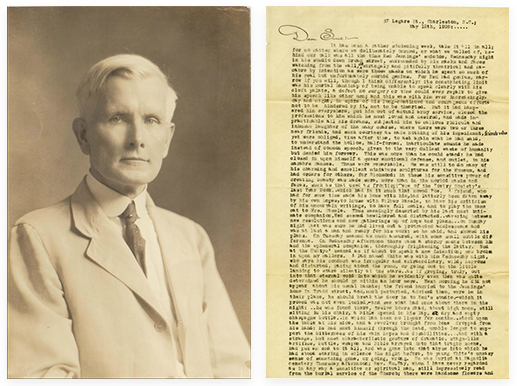

Author John Bennett, a leading figure of the Charleston Renaissance, wrote of Ned Jennings’s suicide in a letter to his daughter, Susan (right).

Author Harlan Greene on Ned Jennings’s tragic end...

The letter in my hand was startling. “It has been a rather sickening week,” it began, “for no matter where we deliberately turned, or what we talked of, behind our talk was… Ned Jennings’s suicide, Wednesday night, in his studio down Broad Street, surrounded by his masks and faces watching from the wall.”

Penned by author John Bennett in May 1929, the letter promised—finally—to answer the myriad questions I had about the artist Edward Ireland Renick Jennings. My interest in Ned, as he was called, was piqued by references in hundreds of letters I had sorted through as archivist for the South Carolina Historical Society in the 1970s. Jennings had not been the typical artist of the Charleston Renaissance; no, indeed, he created fantastic, flamboyant scenes peopled with figures from myth and history and was known for his theatrical masks both humorous and terrifying.

Another thing that intrigued me about him was my suspicion that he might have been gay—and there was precious little information on any aspect of gay lives in any book or archive in the city back then. We ourselves were still living in a semi-secret shadow world in bars on King, Market, and Hayne streets; and so, finding out about Jennings would be a window not just to him, but to a taboo history of which no one would speak.

Those masks—used to hide and reveal oneself simultaneously—offered insight. The artist and author John Bennett described them as “strangely and pitifully theatrical and macabre” on “which he spent so much of his real but unfortunately morbid genius.” He believed that Jennings’s inability to speak clearly hampered him greatly, subjecting him to ridicule. Even friends were “obliged, time after time, to ask again what he had said, to understand the hollow, half-formed, inarticulate sounds he made instead of common speech,” he wrote. “This was more than he could stand: he had closed in upon himself a queer emotional defense, and outlet, in his macabre dances. These were remarkable.”

I had heard about them, the tales of Jennings suddenly appearing at outdoor garden parties at night, dressed (or undressed) like a satyr or Pan, streaking by the startled guests, expressing himself without words, an outlet to the forbidden dreams and passions consuming him. In the theater, he found his métier and release; in a staged world of his own design, actors, resplendent in robes and masks, could strut and pose and speak eloquently, giving reality to his fantasies.

When Jennings became a curator at the Charleston Museum, creating civilization dioramas highlighting Egypt, Babylon, and classical Rome and Greece, he could create past times and glories with skill and expertise. Meanwhile, he himself was constrained in a time and place that rejected him.

“It’s not a crime to dream,” he had written; but it was a crime to be who he was, alienated not just by his half-formed speech, but his homosexuality; the city had founded a Law and Order League in 1913 to close down bars and stamp out “perversion.” Ministers quoted the Bible and called it a sin; and I could not but wonder if the people who jeered at Jennings did so not just for speech but his sexuality, another form of self-expression denied him. Although Oscar Wilde was avoided as the symbol of “the love that dare not speak its name,” Jennings flaunted his attraction to him, in his designs and masks made for Wilde’s play Salome, based on a character who had danced as hedonistically and wildly as he himself had. Bennett could only refer to “out” gay men in town as citizens not of Wessex or Essex, but Middlesex.

Yet Bennett was kindly deposed to Jennings, for in that letter he wrote sympathetically and in code about the young man’s secret life (and we, in those years, spoke in code, too, with careful use of pronouns and vague allusions as to whom we were seeing.) Jennings, according to Bennett, was seeing somebody:

A friend, who had for some time made his

home with him, had lately been drawn away by

his own hopes, to house with [celebrated

writer] Wilbur Steele, to have his criticism of his

uncertain writings, to have full meals, and to

play the tame cat to Mrs. Steele. Thus seemingly

deserted by his last most intimate companion,

Ned seemed bewildered and distracted…

Here finally was a clue: Ned had had “an intimate friend”—the only way Bennett could describe a lover—who had “made his home with him.” Bennett would not name who it was, but I could, checking city directories: Ned and a man named Robert Cameron Sellers were living together at 54½ Broad Street. This was somewhat unusual in an era when even adult children stayed with their parents till they married.

Another gay couple living nearby, Harry Hervey and Carleton Hildreth (those men from Middlesex) were ostracized when it was discovered that they were not professionally linked, a writer and his secretary, but in love with each other. (In 1929, they left Charleston, just as Hervey’s novel of a suicidal gay man was published under the title Red Ending.)

Searching for more details, I found Sellers and Jennings were involved in theater work together, and a “one-man” exhibit of his art work included a drawing by Sellers, too. Were they attracting attention for living together as unmarried artistic men? Were they being unmasked? Could that have panicked Sellers to desert Jennings? And was Jennings, now deprived of a lover, desperate and bereft?

Harlan Greene’s firrst novel, Why We Never Danced the Charleston, was based on Ned Jennings. His latest book, The Real Rainbow Row, is a history of LGBTQ life in Charleston.

“Queering the Renaissance”

November 15

In conjunction with the exhibit, “Something Terrible Will Happen,” award-winning author and historian Harlan Greene leads a special talk illuminating the unacknowledged LGBTQ presence in the arts in Charleston in the early 20th century. Gibbes Museum of Art, 135 Meeting St. Wednesday, 6-7 p.m. $30, $20 members, $15 student/faculty. (843) 722-2706, gibbesmuseum.org