In November 1865, 52 Black men met at Zion Church to combat the state’s proposed black codes

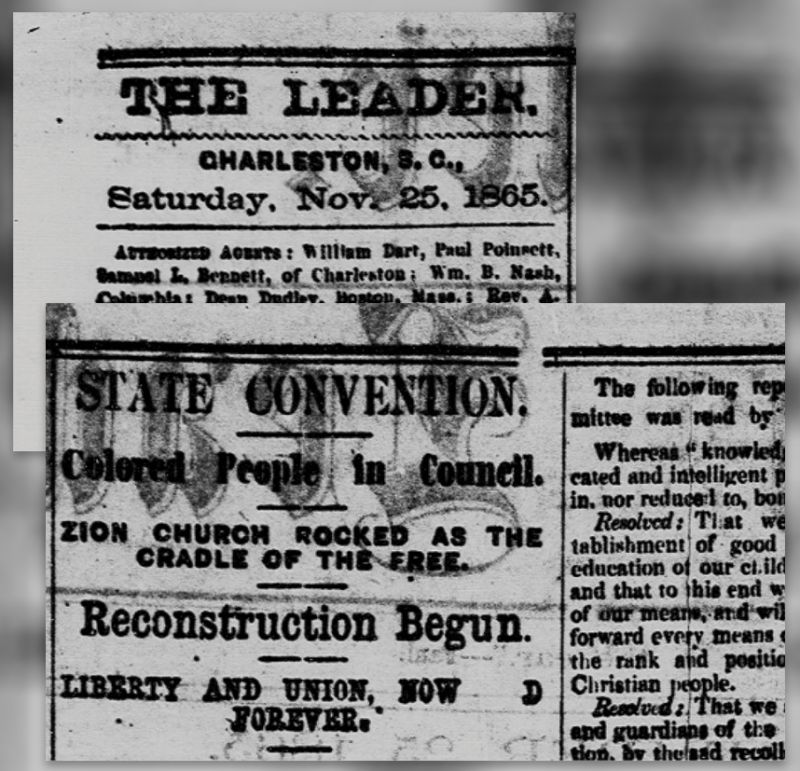

Headlines from The Leader, the local weekly African American newspaper, on November 25, 1865, after ”radical members” of the first legislature since the Civil War met at Zion Church.

There are many occasions to celebrate freedom in America: January first brings Emancipation Day parades. Juneteenth (when enslaved people in Texas learned about the Emancipation Proclamation) is a national holiday. Carolina Day on June 28 commemorates the state’s victory over the British in 1776, and July Fourth sparks fireworks for the fiery words of our Declaration of Independence.

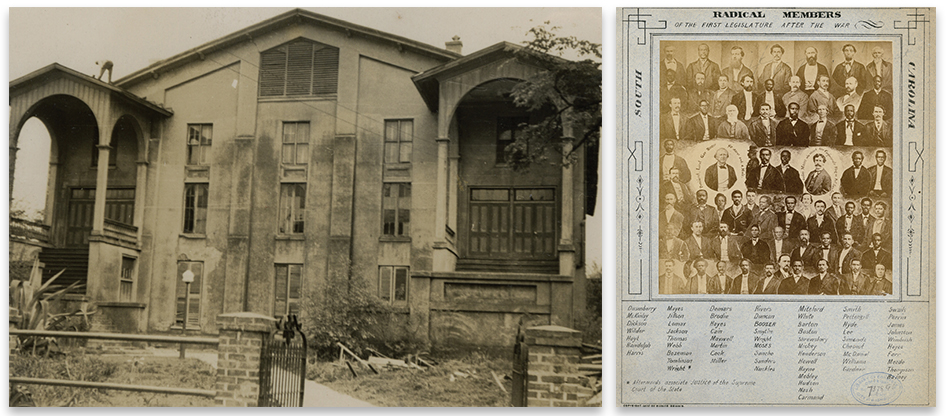

Members of the first legislature (above right) since the Civil War met at Zion Church (above left) to protest proposed black codes and demand that Black men be governed by the same laws as white men.

But uncelebrated is a similar declaration, signed here on November 25, 1865. The Civil War had ended in April, Reconstruction had yet to begin, and the state was passing black codes, laws aimed at keeping formerly enslaved men and women subservient. To combat this tyranny, 52 Black men met at Zion Church, then on Calhoun Street across from where Mother Emanuel AME Church now stands. “We simply desire that we shall be recognized as men,” they wrote, and “that we have no obstructions placed in our way; that the same laws which govern white men shall direct colored men; that we have the right of trial by a jury of our peers, that schools be opened or established for our children; that we be permitted to acquire homesteads for ourselves and children; that we be dealt with as others, in equity and justice.”

This elegant call for equality was unprecedented and epoch-making. But the white men in the legislature voted in favor of the black codes. Reconstruction later overthrew the legislation, but those gains were lost with Jim Crow laws. More than 150 years later, those words ratified in a Charleston church still resonate.