See Mixon's work next month when she's the visiting artist at Gibbes Museum

An Orangeburg native and daughter of agricultural seed growers, painter Katy Mixon grew up with a deeper consciousness of natural rhythms than most. The cycles of planting and harvesting, growth and decay, the land’s changes through the seasons—these are always metaphorically present in her work, be it in the way she thinks about her process, or abstractly depicted in her oil paintings, sculptural pieces, and textiles.

Mixon left Orangeburg in 2002 to attend Davidson College in North Carolina, where she received her studio art degree, continuing to earn her MFA from UNC-Chapel Hill. After spending several years working as an artist in New York, she moved to Charleston in 2019 to be closer to home.

Mixon’s abstract oil paintings, painted quilts, and installations have been exhibited in shows along the East Coast, as well as in the Midwest, Italy, and England. She’s also completed several residencies, including one in Woodstock, New York’s Byrdcliffe Art Colony. We spoke with the painter and crafter as she gears up for a busy year, beginning in February with a three-month engagement as a visiting artist at the Gibbes Museum.

Evolving & exploring: I work in multiple layers [with oil paints]. I start with monochromatic layers, with gradient shifts in each one. Once those are dry, I carve into them. Of all the variations you’re seeing on the surface, most are from the previous layers of paint. When I started, I was using canvas, but puncturing it, so I use wood panels now. I usually find someone local to make those for me. The carved panels I’ll exhibit as finished pieces, and the carved paint pieces I often use to create temporary installations in specific spaces.

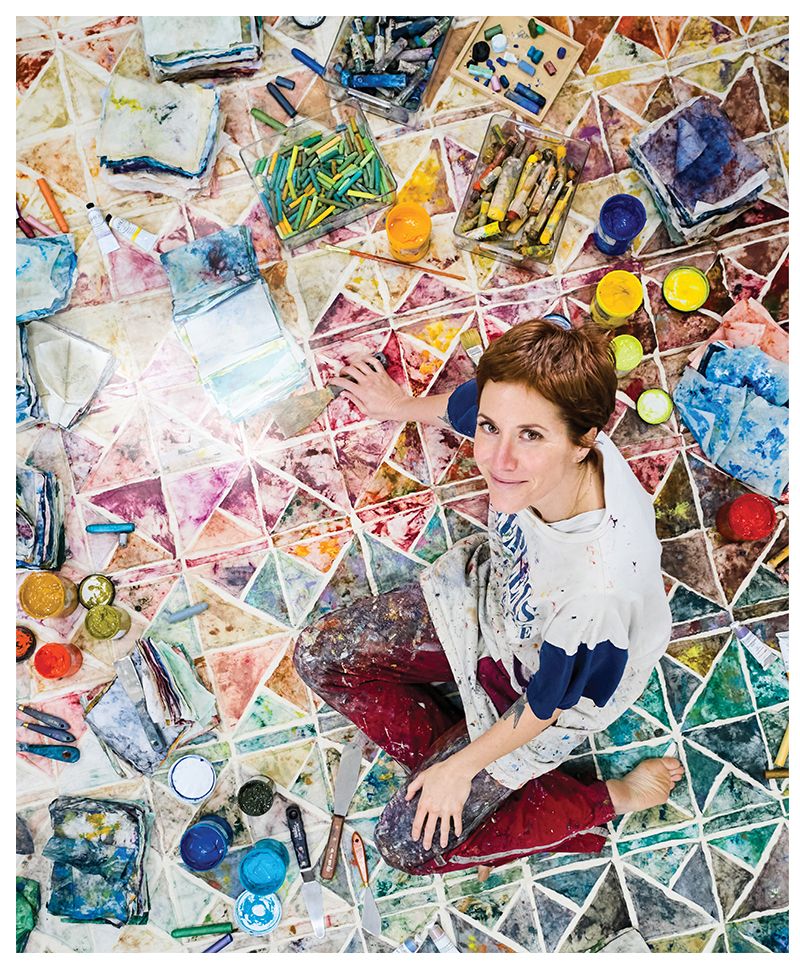

Crafts(wo)manship: Both my grandmothers were quilters and sewers, and so I started repurposing my studio rags into these pieced quilt tops. I was throwing the rags away for the longest time, and then I realized that my trash can was full of these beautifully stained cloths. I usually pin the pieces in studio, and then I work with a local quilter to add the batting and backing. I typically finish them with hand-stitching or embroidery. I really like working with local craftspeople to realize some of these pieces. It’s been fun and collaborative, learning about these crafting traditions.

Sustainable art: I think about my studio as its own little ecosystem. I am really aware of things that catch paint—including baby wipes and cloths I use to clean up—and try to reuse anything that’s part of the making process without being part of the painting.

Natural inspiration: My work is very landscape based, but for most people, it comes off as abstract. I go for walks and pick things up—I’m a collector of little things, anything I can possibly use. And I do a lot of landscape drawing. So many of the influences for my work, in terms of texture and color, come from the natural world. I think about the surfaces as, not so much a depiction of a landscape, but of the active, natural processes of land—this building up and then erosive action.

Paint towers: The way the tower, Horizons, emerged is that for a long time I was going to this local hardware store to buy leftover paint, or cans that they had when they mixed a color wrong—they’d sell it to me for, like, a dollar. I’d lay out plastic on the floor and then pour out the paint and make these sheets that I could then cut and manipulate. I was weaving a bit and figuring out how to use them. That tower has a wooden core, and the rest is all layers and layers of paint. It’s a little over six feet tall. What I love about it is that it feels like a human-sized core sample of a painting. It’s really interesting to me to take paint, which has real body and is so malleable, and put it through all these transformative changes of state.

Inviting viewers in: My work is always about how much of the process I can make visible to the viewer, taking them through the evolution of this paint: from palette, to panel, to object. It’s not so much about a singular painting on the wall, but about it as part of this larger practice—making that visible would be a success.