There were boxes upon boxes, then more boxes. Crates stacked on crates. Inside were carefully wrapped canvases, delicate collages, various sculptures, Plexiglas installations. Watercolors, pen washes, oils, and charcoals; woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, and trays upon trays of 35 mm slides. Paintings with 1950s museum tags still on them. And journals. Shelves of dated and numbered journals—six decades worth of ideas, sketches, designs, questions, commentary, to-do lists (“measure the Hudson River”), scattered thoughts, scribbled dreams, articulate rants, and gorgeously rendered fantasies. An artist’s frisky and fantastic mind spilled out on pages and pages, a compulsive creator’s catalogued journey.

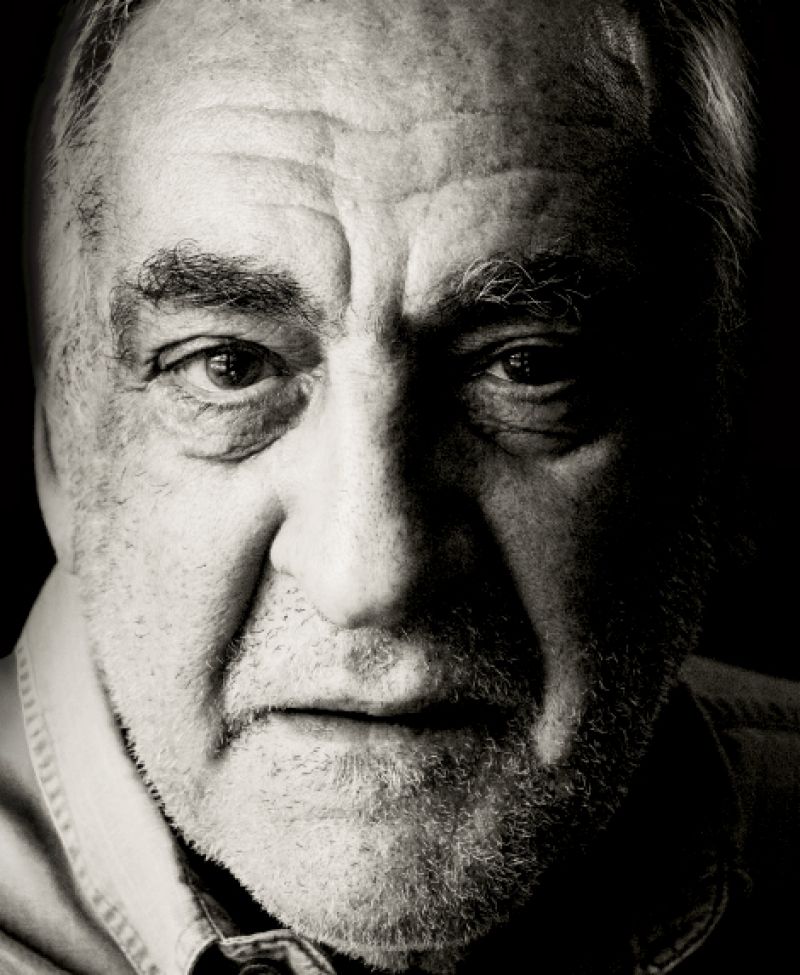

Don ZanFagna’s creative journey has culminated here, in Mount Pleasant, where he and his wife, Joyce, moved about two years ago. The 82-year-old artist’s meticulously packed crates and boxes now sit in the FROG (finished room over garage) of a quiet subdivision. Kids on bikes and moms pushing strollers walk past the unassuming split-level, with no idea that inside sits an artist’s lifetime of work—remarkable museum-quality work—none of which has been seen in decades.

Zan-Who?

Don ZanFagna’s resumé seems improbable: West Point cadet, college jock, Boston Red Sox draftee, ditto the Dodgers, ditto San Francisco 49ers and St. Louis Cardinals, Fulbright scholar, fighter pilot, artist, professor, university art department chairman, environmental activist, architect/designer, father, husband, uncle. But true it is, and ZanFagna is none too impressed with much of it, except the part about being a husband, a father, and an artist. The work. Always the work. “I’ve never wanted to answer to anybody but the work itself,” ZanFagna says emphatically, his gravelly arrhythmic voice a work of art itself.

Despite ZanFagna’s early success in West Coast galleries, despite showing his work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Pasadena Museum of California Art, and in nearly 200 exhibitions nationally and internationally, ZanFagna has had no interest in the commercial art world since the late 1960s, when he left California for the edgier, more organic New York art scene. “He didn’t want gallery owners telling him, ‘Hey, do more like this, this sells, that doesn’t’,” explains Everett White, ZanFagna’s nephew and a fellow artist who runs the Everett White Gallery on Sullivan’s Island with his wife, Joanna, and partner Gamil Awad. “Uncle Don,” as they call ZanFagna, wanted only to nurture and indulge his unedited creativity, to follow raw inspiration.

“I’m an artist in spite of myself,” says ZanFagna, who began to hone his artistic

inclinations after a football teammate at the University of Michigan (where he transferred from West Point) suggested he try an art class. ZanFagna had always had creative aptitude—at age 14 he worked for government contractors sketching parts for airplanes—but ZanFagna was also an aeronautical engineering major, star quarterback, and standout third baseman for the Wolverines. Nonetheless, he changed majors and graduated with a degree in art, architecture, and design. And then, to the head-shaking dismay of many, he turned down a $30,000-a-year major league baseball contract (that’s in 1950s dollars) to pursue his artistic passion. Following a tour of duty in the Korean War, ZanFagna’s first stop as a working artist was Italy, where he studied European masterworks on a two-year Fulbright scholarship. Accompanying him was Oberlin-trained artist Joyce Peck, his muse and bride-to-be.

Those formative years in Europe launched a career that has spanned half a century. ZanFagna has produced work prodigiously, but for at least the last 30 years, he has not put it “out there” for sale in galleries or exhibitions; instead he’s put it away. And thus the treasure trove is only now—thanks to Everett, Joanna, and local art enthusiast Allison Williamson, along with Uncle Don’s blessing—beginning to trickle out into the world.

All Over the Map

“My initial impression was I’m looking at a guy who probably studied in Italy, with some influence by the Metaphysical School,” says George Read, a Harvard-trained art appraiser and critic, who was invited by Joanna and Allison to assess their discovery. Read saw the work cold. Along with virtually everyone else in the current art world, he’d never heard of Don ZanFagna. “I was first struck by how stylistically inconsistent the body of work is. It’s almost stream of consciousness, all over the map,” he says. “So then, without a cohesive narrative to tell the artist’s story and trace his progression, you have to ask, ‘Well, is it any good?’ My answer is yes, it’s quite good. There’s a disciplined talent there, a real gift at work. This is someone who combines disparate elements in a highly sophisticated way to produce images that are challenging and compelling.”

Local artist and collector Anne Darby Parker had a similar response when she happened upon ZanFagna’s work in the back of what was then the Island Gallery (now Everett White Gallery). “One moment I’m looking at landscapes and palm trees, then I go into this back room and it’s, ‘Whoa, where did these come from?’ I was riveted,” Parker says. She was particularly taken with ZanFagna’s tissue-paper collages, which were created during a tender period when Don and Joyce’s only child, Robert, was gravely ill. “So delicate, translucent, and beautifully transposed, they looked like music,” she says.

ZanFagna’s body of work includes series upon series, with some recurrent and overlapping themes, though the only constant thread is a studied and disciplined whimsy. Individually they represent experimental periods and creative tangents in life chapters, but overall there is no ongoing story line; compared to one another, the series are largely incongruent in style, medium, and message. Actually, strike that last bit. ZanFagna insists his work is about pure “expression” as opposed to intentional message. “If I wanted to send a message, I’d go to Western Union,” he quips.

For the Future

Take in the lot of it, and one thing is clear: ZanFagna is a serious and broad thinker who, intentionally or not, confronts the viewer with questions or what he calls “signals… warnings” to ponder. In his prime, he was an innovator and visionary, dialed in to the culture and avant-garde ethos around him. He directed the art department at Rutgers University and kept company with left-brain luminaries of his day: Andy Warhol, Al Hansen, Buckminster Fuller, Charlie Mingus, and Yoko Ono, with whom he collaborated on her art “Happenings.” He pushed boundaries and sounded alarms, especially related to concerns of the environment. Long before Al Gore’s environmental campaign, ZanFagna founded CEASE (Center for Ecological Action to Save the Environment) and was a speaker, along with Ralph Nader, Margaret Mead, and numerous others, at New York’s first Earth Day Teach In at Union Square in 1970.

ZanFagna’s zesty mind took existentialism, entwined it with ecological awareness, then injected it with architectural savvy and came up with the Infra/Ultra Architectural Foundation, an ecological design think tank of sorts, out of which grew his “Pulse Dome” series, which explored the futuristic concept of “growing your own house.”

His journals examine the nature of change and upheaval amid the uncertain frontier where technology, robotics, space exploration, DNA/biology, ecology, sexuality, and “cosmic relativism” were all coming together. ZanFagna would then distill rampant thoughts into something as simple and poetic as his “Micro-Max Pocket Systems I and II,” which was exhibited at the Whitney Museum in 1976 and featured a Plexiglas sculpture titled All the Books of the World in the Palm of Your Hand—30 years before the Kindle.

“Uncle Don has always said that an artist’s responsibility is to educate the future,” says Joanna. And now the “future” has proved him prescient. “He seems to be equal parts mad scientist, engineer, architect, and visionary,” notes Mark Sloan, director of the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, who is planning a travelling exhibit of ZanFagna’s “Pulse Domes.” In the series, the artist imagines a home created, constructed, and maintained with all organic processes, in perfect harmony with nature. “There are now several research projects around the world looking seriously at the possibilities of such a model (e.g. the Biosphere 2 project in Arizona),” says Sloan.

Show & Tell

“It’s been like Christmas morning, every day, for months on end, opening these treasures and unwrapping mummified works,” says Allison Williamson. Once unpackaged and cataloged, the question becomes, what to do with it. What does the artist and the family want? How do you respect this body of work?

ZanFagna has agreed for his art to be shown and some pieces sold—“Yeah, it’s about time, I’m ready...,” he says—though financial gain is not his motivation. “I’ve gotten what I needed to get from the work,” he says. Joanna, Everett, and Allison feel obliged to share Uncle Don’s creative vitality and talent with others. They’ve sought the counsel of experts who have evaluated the work, including Sotheby’s and George Read. And they’ve received positive response from initial inquiries to select museums. To date, the Tampa Museum of Art and the Aspen Art Museum, in addition to the Halsey, plan to host exhibitions. And a documentary, Rediscovering Don ZanFagna, produced by Kevin Harrison and Tim McManus of PDA Productions is scheduled to premier at the Charleston International Film Festival this month. Meanwhile, Everett and Joanna continue to showcase selections of Uncle Don’s work at their gallery, more for exposure than for potential sales, as their intention is to protect the integrity of the work as a whole. To let the art tell the Don ZanFagna story—a story of art for art’s sake, of stumbling into wonder.

See the work

Film Premiere

May 19: Rediscovering Don

ZanFagna, Thursday, 6 p.m. American Theater, 446 King St. www.charlestoniff.com

Exhibits

Ongoing: Everett White Gallery,

2214 Middle St., Sullivan’s Island. To view the series in full, visit

October 20-November 20:

“Pulse Dome” series, Aspen Art Museum, Colorado. www.aspenartmuseum.org

October 28-January 2012:

“Cyborg” series, Tampa Museum of Art, Florida. www.tampamuseum.org