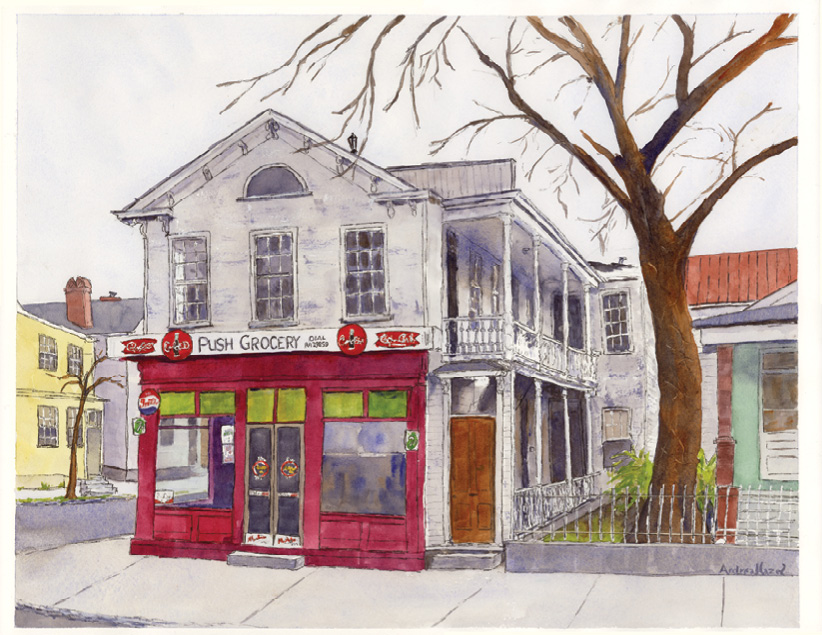

Her series “How It Was—Charleston in 1963” depicts homes and streetscapes that were demolished to make way for the Crosstown

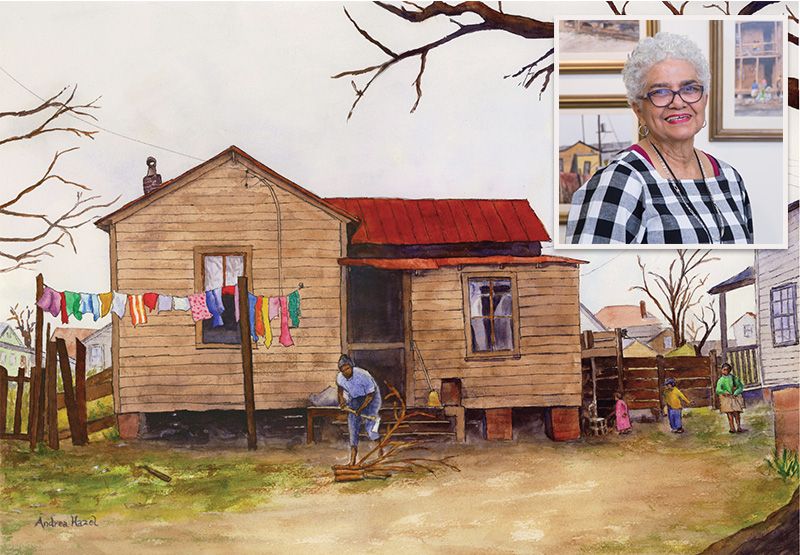

Andrea Hazel (pictured inset) documents her childhood neighborhood in the series ”How It Was—Charleston in 1963,” which includes Choppin‘ Up Some Wood (watercolor on paper).

Andrea Hazel knows something about upheaval. Her initial residency at the Gibbes Museum of Art started right before COVID-19 hit and the institution’s doors suddenly closed. Fortunately, the Charleston native is back at the Gibbes through November 22, showcasing work that is a testimony to change. Her series, “How It Was—Charleston in 1963,” depicts homes and streetscapes she knew as a girl growing up on Ashley Avenue—homes demolished to make way for the Crosstown.

The roadway gashed through a once-vibrant, tight-knit Black community and suddenly shifted ways of life for neighbors who lived there. “Most of the construction happened when I was away at college. I came home for break once and had fallen asleep on the Greyhound bus. When I woke up in Charleston, everything was so different I didn’t recognize where I was,” says Hazel, who taught math at Trident Tech for most of her career and ran a photography business on the side before discovering painting later in life.

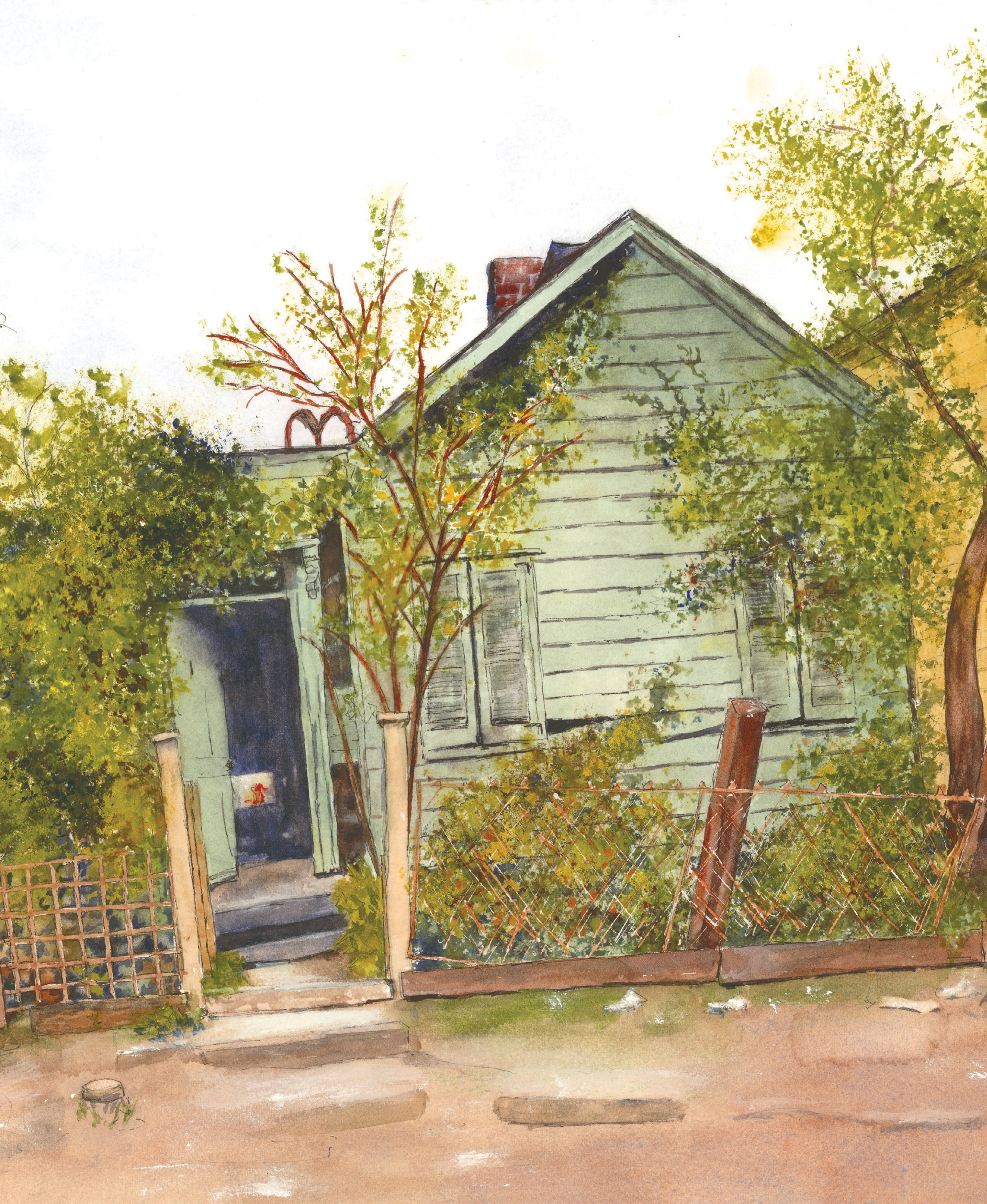

The artist, now 72, also paints landscapes and produces a calendar of her watercolors every year, but this series has captivated her imagination and memory in a powerful way, especially as many peninsula neighborhoods gentrify and succumb to development. “I don’t want to forget who we are and our history. I’m trying to document what was there,” she says. “They were beautiful homes. Sure, some areas were rough, and some people lived in squalor, but that’s part of who we were, too. I’m trying to show all that.”

Though Charleston is known for preserving its history, there are communities, such as the downtown neighborhood where 72-year-old artist Andrea Hazel grew up, that have been destroyed to make way for easier transit and development. In her recent work—including the painting Miss Minnie’s Cottage (watercolor on paper, 13 x 17 inches)—the photographer-turned-watercolorist encourages viewers to remember and appreciate “How it Was.”

Becoming a Painter: I started painting in my 50s, thanks to my husband Frank Hamilton, who thought I was working too hard. (I was still teaching at Trident and photographing weddings on weekends.) He said I needed to “calm down,” so he gave me a set of paints, paintbrushes, and watercolor paper. As a photographer I was used to “seeing;” I understood composition. In college at Marymount in New York, I’d taken art history and loved going to see art in the city. The first museum I ever went to was The Met. We, of course, had the Gibbes here, but it wasn’t open to me as a Black girl. Turns out that I just took to watercolors. At age 60, I took oil painting courses at the College of Charleston. I was the oldest person in the room, but I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Inspiration: I was playing around online and came across photos from the Department of Transportation in the SC Digital Library. Surveyors had documented houses and streetscapes while determining where the Crosstown would go. I was mesmerized—this was my neighborhood. The images were things I remembered. I must have looked at them for at least a year. Historic Charleston Foundation held the rights, and I asked for permission to paint from them. My dad was a restoration carpenter and worked on many of these houses. I guess this is my way of building and fixing houses like he did, my way of being the carpenter’s daughter.

The corner store depicted in Push Grocery (watercolor on paper) was on Fishburne and St. Philip streets.

Creative Process: First, I draw a grid to get the proportions right—I want it to look correct. I’m painting from black-and-white photos, so I have to think to remember details and colors. One house is where my friend Millicent Brown grew up, so I called her to ask the color of the roof, the awnings, but often I have to wing it. Once I get the drawings down, I ink them, so they look a little crispy, have some snap. Then I start painting, little by little, taking my time.

Late Bloomer: I believe as you get older, the more of yourself you become. You’re freer to allow what is in you to come forth. And the response I’ve gotten from people is just amazing. A white woman now in her 80s and living up North saw my painting online of a house on the corner of Jackson and Nassau streets, where she had grown up. Seeing it, she told me, took her way back—as far as she considered, she was back in her grandmother’s kitchen. I try to touch those tender memories in people. There’s so much greed and selfishness; I’m trying to take people back so they remember kindness.

See more works from her series

Learn about her residency at the Gibbes Museum of Art