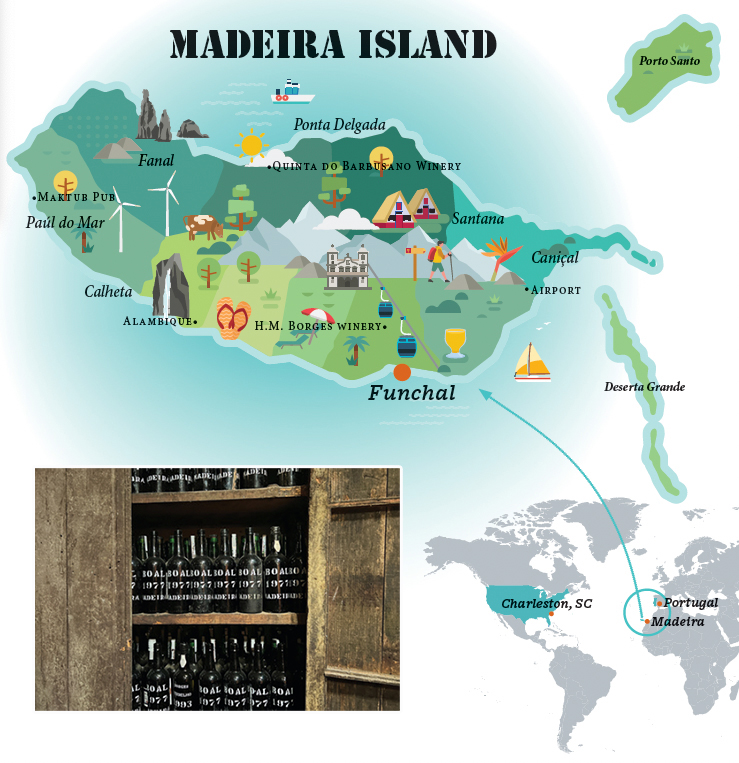

Madeira island has long been connected to Charleston via seagoing trade routes and its fortified wines

After a morning of steadily sipping Madeira wine vintages of increasing rarity, my host—Helena Borges, the fourth-generation owner of H.M. Borges winery—pulls one of 500 remaining bottles hand-labeled “1986” from the shelf. For 35 years, this Madeira Boal rested in an oak barrel in her family’s warehouse. Helena is proud but nonchalant as she fills my glass.

The elixir is equally savory and sweet, a tender but explosive amalgam of caramel, tobacco, and plum that’s best compared to a decades-old bourbon in its layers of complexity. Even after a week of tasting the island’s best, I’m taken aback. I understand the centuries-old fuss.

Aged and fortified Madeira wine was a staple of Charleston’s social life in the 18th and 19th centuries. I’ve traveled to this steep, rocky island in the Atlantic to chase a bit of our city’s history, sampling vintage Madeira along the way. From a humble, dark tasting room at H.M. Borges headquarters in Funchal, the island’s capital, I’m transported around the world—to France, the source of the finest oak barrels, imparting their essence on the wine; to Charleston, where our ancestors toasted births, marriages, and visiting dignitaries with this distinctive spirit; and outside to the steep, terraced slopes of this sparkling archipelago, 430 miles west of Morocco.

Helena Borges (above left) is the fourth-generation owner of H.M. Borges, where fortified wines age for decades in French oak barrels.

Although Madeira includes four islands, only two are inhabited, and most Madeirans live on the largest, namesake island. Visiting from the US has long required flying to continental Europe and backtracking across the Atlantic. The journey, often stretching to 15 hours or more, has been cut in half. Azores Airlines offers a weekly direct flight from New York’s JFK airport, making Madeira more accessible from Charleston than ever before. The destination is also surging in popularity, landing on the cover of Travel + Leisure in 2023 as the readers’ pick for best European island.

Madeira is to Portugal as the Virgin Islands are to the US—technically part of the country, but autonomous and more relaxed. I arrive in Funchal excited but sleepy after the seven-hour, red-eye journey from JFK. Immediately after taking my bag, the concierge at the Savoy Palace hotel offers an effective remedy: poncha. High-proof rum—known locally as aguardente (fire water)—forms the base of Madeira’s favorite cocktail. It’s balanced with honey, lemon, and sometimes orange juice.

Madeira Bound - Since a direct flight from New York cut travel time in half, more American travelers have been making the trip to the Portuguese island that offers luxury and adventure—and a sip with a historic connection to Charleston. Azores Airlines flies from New York’s JFK airport to Funchal once a week, currently on Sunday nights (allowing time for a same-day connection from Charleston). Direct return flights are currently on Tuesdays. azoresairlines.pt; (inset) Vintage Boal wines at H.M. Borge.

“If you drink three ponchas, you’re going to start speaking Portuguese,” says one new friend. “Poncha can cure everything from a bad cold to a broken heart,” says another. I suffer from neither at the moment, but I enjoy a few ponchas during my week on the island, even finding a popular roadside stand near the village of Santana where it’s made to order with a wooden muddler called a caralhinho.

Groggy but energized on that first morning, I soak in the view from the pool deck at the Savoy Palace. The ancient volcanic island’s topography recalls Kauai—steep mountains that drop precipitously into the ocean, leaving only tiny, rocky beaches in the folds. Most of Madeira’s population lives on the arid and subtropical south shore, while the vineyards are found in the wet, lush north. Atop the 35-by-17-mile island’s central ridge, a cloudy, damp forest invites long hikes through ancient laurel groves and across rocky peaks. My itinerary includes morning treks through these jagged, green mountains, followed by long afternoons eating local fish, drinking wine, and simply enjoying the ubiquitous views.

(Left to right) Dramatic views along Madeira’s east end and its famous cliffside trails; Pedro Albuquerque, a guide with BraveLanders 4x4 tours, beside his Land Rover; Stratton pauses to admire a bird while hiking along a levada—a canal used to divert water to farms below—in Madeira’s mountainous forests.

Accessible Adventure

A generation ago, circling Madeira required three full days of hairpin, switchback roads to navigate the tightly folded coastal slopes. A series of tunnels—some over a mile long—now make zipping around the island more efficient. “This island is like Swiss cheese—full of holes!” jokes Pedro Albuquerque, my guide with BraveLanders 4x4 tours, as we dash from coast to coast.

On a cross-island trek, I experience all four seasons in a day, waking up to the sunrise across the ocean before driving into the mountains for a long trail run through the thick cloud forest. On century-old dirt tracks, Madeira’s true character comes into view. Nearly 500 miles of levadas—ingenious canals built to deliver water from the mountains to the coast—encourage leisurely walks through undeveloped countryside. All around, rough-skinned farmers scale endless ladders bridging stone-walled terraces, lugging hundred-pound loads of bananas and vegetables.

Madeira finds the sweet spot between a still-vital agrarian economy and a luxurious island retreat where locals appreciate an enthusiastic “olá” but most speak English. On the north coast, I breaststroke through an ocean-rinsed volcanic pool while gazing at waterfalls pouring from cliffs into the sea. Back in Funchal, I stroll through a dizzying kaleidoscope of colors at Monte Palace Tropical Garden. But my best Madeiran moments come whenever I stop to sit and breathe in the ocean vista that’s visible from almost everywhere on the island—a bliss I can often extend across an entire meal.

(Clockwise from top left) Engenhos do Norte (North Mills Distillery) produces their rum in a 1927 factory and mill; Maktub Pub’s, a favorite for surfers, menu of beverages; grilled limpets; Maktub Pub in Paúl do Mar; roasted chestnuts for sale on the street in Funchal.

Dine in Style

Travel often requires deciding between a restaurant with a view and one known for its food. In Madeira, there’s no compromise. At Avista, atop the Les Suites Hotel in Funchal, the dining room is encompassed in glass, showing off an unobstructed seascape of the archipelago’s uninhabited offshore islands. I order the scabbardfish, a local specialty with an appealing texture somewhere between scallops and a flaky whitefish, and a glass of refreshing local wine that’s a vinho verde in all but its provenance.

On another evening at Alambique, a fine dining restaurant at the Savoy Saccharum hotel (one of seven Savoy properties on the island), I indulge in a seven-course prix-fixe tasting menu that draws heavily from island-grown produce. Even with added wine pairings, a divine, decision-free dining experience is often available on Madeira for around $100.

Many of the island’s best meals emerge from more humble kitchens. After a walk along forested levadas one morning, I arrive at an open-air spot in Fanal, home to the island’s oldest laurel trees. While chunks of sirloin roast on a laurel skewer over fire, hiking guide Elise Quintal Dias pours a glass of wine into a paper cup and urges me to dig in: “A bit of bread, a bit of meat, don’t be shy, just eat.”

It echoes my experience at Maktub Pub, in the west coast surf enclave of Paúl do Mar. Owner Fabio Alfonso brings a whole snapper to the table, harvested from the ocean hours before. His restaurant is a local favorite for summer sunsets and a destination for serious surfers (at the table next to mine, world-renowned big-wave riders Twiggy Baker and Greg Long swap stories). With confident swagger, Alfonso expertly filets the snapper, curing a perfect tableside ceviche. A simple, caipirinha cocktail of aguardente, sugar, and lime (just four euros!) washes it down. Pressed to describe his island, Alfonso utters, “Here, one can truly forget the world and tend one’s vegetables.”

That also sums up the vibe at Socalco Nature, a boutique hotel perched on a nearby cliffside along the island’s western shore, where I spent the second half of my trip. From my room and private patio, the only obstructions to the ocean views are grapevines, used to produce the house label, Galatrixa—named after the island’s omnipresent lizards. Socalco’s elaborate breakfasts and dinners are sourced from an on-site garden, and meals always include house-baked sourdough, leavened with the chef’s family’s culture nurtured for 200 years.

Madeira is a lot like that sourdough starter. It’s remained relatively unchanged for centuries. Away from the villages, apart from a few invasive plants like eucalyptus trees, Madeira looks much as it did 600 years ago. Its remote, mid-Atlantic location means there’s been no large wave of immigration in its history, keeping the traditional farming culture largely intact. The island’s two soccer teams—one of which produced superstar Cristiano Ronaldo, for whom the airport is named—generate more friendly debate than actual politics. There’s no rush here. I’m not running late for anything. The world feels tranquil and right.

(From left) Santana, a small town on the north coast, is renowned for its thatched-roof A-frames. Color abounds on the island, from the lush forests to the pastel paint colors seen along the sunny southern coast.

Connecting the Dots

Without Madiera’s grapes, I likely wouldn’t be here. It’s the island’s fortified wine—a staple in Charleston parlors until most collections were cleared out by Union troops after the Civil War—that made me want to follow a ghost from my city’s past.

Madeira—the wine—was discovered by accident. When islanders first exported barrels of their traditional wine to the New World, they noticed the intriguing, rich flavor of the returning remnants. Surmising that time in the steamy tropics enhanced the flavor, winemakers developed a process of heat-fortification that led to Madeira wine as we know it. Their product grew in popularity, and the island’s vertical slopes were carved into unforgivingly steep but arable terraces to accommodate vineyards.

Modern Madeirans also embrace the refreshing table wines that the high acidity and salinity of their soils produce. Local vinhos tintos (red) and vinhos brancos (white) are on par with Europe’s best, yet are widely available on the island for $5 to $10 a bottle.

I spent my final afternoon in Madeira at Quinta Do Barbusano, a vineyard opened by António Oliveria in 2006. The tasting experience at his rural estate—paired with a traditional espetada lunch of sirloin grilled on laurel skewers over an open fire—may be the island’s finest. From the patio, I gaze inland at the terraced agricultural slopes, and it feels like Machu Picchu might be just around the corner, yet over my shoulder are the azure waters of the Atlantic.

One measure of travel is the gravity of the memory long after you return to your routine. Does it roll through day-to-day thoughts like the pleasant warmth of a decades-old Madeira wine on the back of the throat? Do you subconsciously steer conversations to your trip, keeping the memories as ever-present as the island’s endless blue horizons? Do you savor every moment of life just a little bit more? Madeira checked each box for me. In a few years, when I finally crack open the bottle of H.M. Borges Boal 1986 tucked away in my closet, I know the magic and wonder I felt on this stunning rock out in the Atlantic will come rushing back.

(Clockwise from top) Saccharum Resort & Spa, another Savoy Signature property, overlooks the coast near Calheta; BraveLanders 4x4 tours explore the mostly undeveloped island; Experiencing Funchal via a cable car that travels nearly two miles as it ascends the city’s steep mountainside.

Quinta da Casa Branca: Escape the city without leaving the capital at this former English estate with fine dining. $250/night, Funchal. quintacasabranca.com

Savoy Palace: This sprawling property near Old Town withholds no luxury. Don’t miss the rooftop infinity pools. $250/night, Funchal. savoysignature.com

Socalco Nature: Suites with ocean views, set within a vineyard in a quiet part of the island. $200/night, Calheta. socalconature.com

Alambique: Prix-fixe dinners at the indulgent Savoy Sacchurum resort in Calheta; savoysignature.com

Avista: The sister restaurant to Michelin-starred Il Gallo D’Oro, with views and flavor for miles; portobay.com

Blandy’s: Aging fortified wines in Funchal since 1811; blandys.com

H.M. Borges: Historic Madeira winery and tasting room in Funchal; hmborges.com

Maktub Pub: Casual beach bar for cocktails and the daily catch in Paúl do Mar; facebook.com/MaktubPub/

Quinta Do Barbusano: Palate-opening table wines and fire-roasted espetada lunches in the São Vicente Valley; search quintadobarbusano at facebook.com.

BraveLanders: 4x4 tours, including culinary excursions with a traditional espetada lunch of grilled steak; bravelanders.com

Freeride Madeira: Mountain biking tours and rentals; freeridemadeira.com

Madeira Trail Tours: Guided hikes along levadas and the ancient laurel forest; madeiratrailtours.com

Travel to Portugal not in the cards? Wine pro Sarah O’Kelley of Grape to Table rounded up some local offerings. Note: the following are typically three-ounce servings.

Charleston Grill

Madeira Flight, 1.5-ounce tastes of the following vintagesob, $199

By the Glass:

D’Oliveira Sercial 1973 $59

D’Oliveira Sercial 1969 $99

D’Oliveira Sercial 1907 $249

Edmund’s Oast

Rare Wine Company Charleston Sercial $20

FIG

Rare Wine Company Boston Boal $23

Rare Wine Company Charleston Sercial $23

Lowland

Rare Wine Company New York Malmsey $23

Sorelle

D’Oliveira Malvasia 2000 $50

D’Oliveira Bual 1992 $60

D’Oliveira Terrantez 1988 $95

Vern’s

Rare Wine Company Charleston Sercial $20

D’Oliveira Sercial 1999 $60

Plus a cocktail featuring Madeira with white Port, Manzanilla Sherry, and orange bitters

Zero George

Rare Wine Company Charleston Sercial $16

1999 D’Oliveira Sercial $26

1992 D’Oliveira Bual $48