Find out about a collobrative exhibit with Mary Edna Fraser urging residents to take action to protect the waterways

Lives: James Island; Family: Wife, Jeralyn, and children, Aiden and Jack; Education: Biology from College of Wooster, master‘s of environmental studies from College of Charleston, and J.D. from Charleston Law School

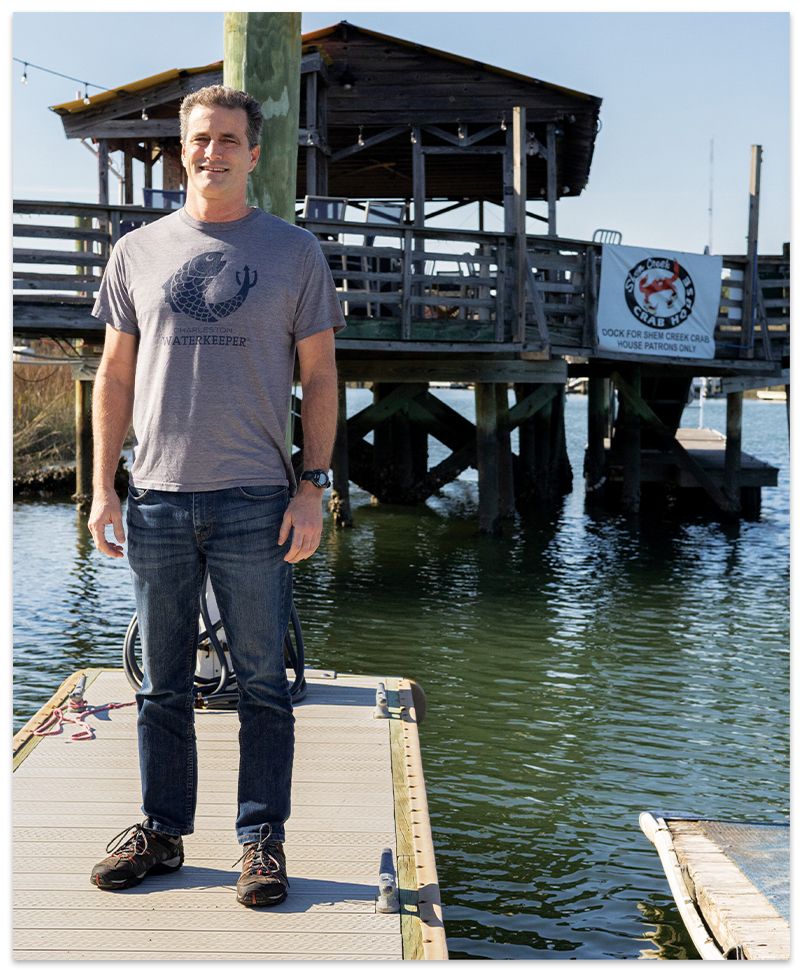

Andrew Wunderley has been surfing on, swimming in, fishing from, and fighting for local waterways for years. And since 2015, he’s worked to protect and restore the coastal network of rivers, marshes, and the Atlantic as the director of Charleston Waterkeeper, a nonprofit founded in 2009. Armed with a dedicated staff and more than 1,500 volunteer scientists who help with projects throughout the year, Wunderley advocates for the health of our aquatic resources.

A competitive swimmer who grew up in Ohio, Wunderley moved to the Lowcountry in the mid-’90s to coach swimming and guided local marathon swimmer Kathleen Wilson to a successful crossing of the English Channel in 2001. He earned a master’s of science in environmental studies from College of Charleston, and in 2008, his Juris Doctor degree from the Charleston School of Law.

This month, Charleston Waterkeeper is partnering with the Coastal Conservation League, the SC Environmental Law Project, and artist Mary Edna Fraser on a “Delete Apathy” exhibit at City Gallery, which will use paintings, sculptures, and videos to call attention to environmental threats. Here, Wunderley talks about what his job entails.

CM: What’s a day as the Charleston Waterkeeper like?

AW: We do a lot of desk research before we hit the water to sample for pollution. Then we gas up the boats, bring along the people we want to show our investigation, and travel to our destination. That is when the sampling from water to sediment begins using sophisticated sonar to locate the fallout. We look at flora and fauna as this can often tell us quite a lot. It’s a little bit of police work and a little bit of science.

CM: How has your role evolved?

AW: What we’ve tried to do is to keep our costs low and leverage technology to broaden our impact and our voice. The thing I’ve seen change in these past 10 years is that there is so much more of everything. That’s people, development, and aggressive growth. Everything we do as a community on the land impacts the health of our waterways, so the threats have only exponentially grown. What we do right now will determine the community that we leave to our kids in the next 20 or 30 years.

CM: What are we not talking enough about as it pertains to our waterways?

AW: I see a lot of really unhealthy marsh. It’s related to sea-level rise, higher tide cycles, and flooding. Every time it floods, all that fresh water is draining into a system that’s brackish. When that water drains away, salinity levels drop and stress the marsh plants. Also, we’re seeing higher pH levels making the water more acidic. That is a problem for oysters—making it harder for them to form a strong shell.

CM: Tell us about the City Gallery exhibit with batik artist Mary Edna Fraser, sculptor Jeff Kopish, and other groups.

AW: It’s an interesting way to push the boundaries. I thought at one point it was all about science and policy, but the way that artists are able to interpret these complicated issues with a unique viewpoint has been a big eye-opener.