Charleston is famous for its multi-steepled skyline and with some 400 houses of worship on the peninsula alone, one can see how Charleston earned the nickname the ”Holy City.”

While these architectural pinnacles symbolically reach for the heavens, they’ve also served important, practical purposes throughout history—from watchtowers to navigational aids for mariners entering the harbor. From their heights, the Sunday and holiday morning air is filled with the glorious peal of bells. Learn more about these historic spires

Beacons of Light The tall spire of St. Michael’s (right) has stood as a daytime navigational landmark since the church was completed in 1761. When St. Philip’s steeple was added between 1848 and 1850, a beacon was installed that served as the rear marker in a set of lights that led vessels from Fort Sumter to the city. The beam remained active until 1915.

Peals of Glory Steeples also operate as bell towers, and while some churches ring only one bell as a call to worship, others have multiple bells that are rung in elaborate musical patterns known as “changes.” St. Michael’s Church, the Cathedral Church of St. Luke and St. Paul, and Grace Church Cathedral each have a complete ring of eight bells, giving Charleston more change-ringing towers than any other city in North America.

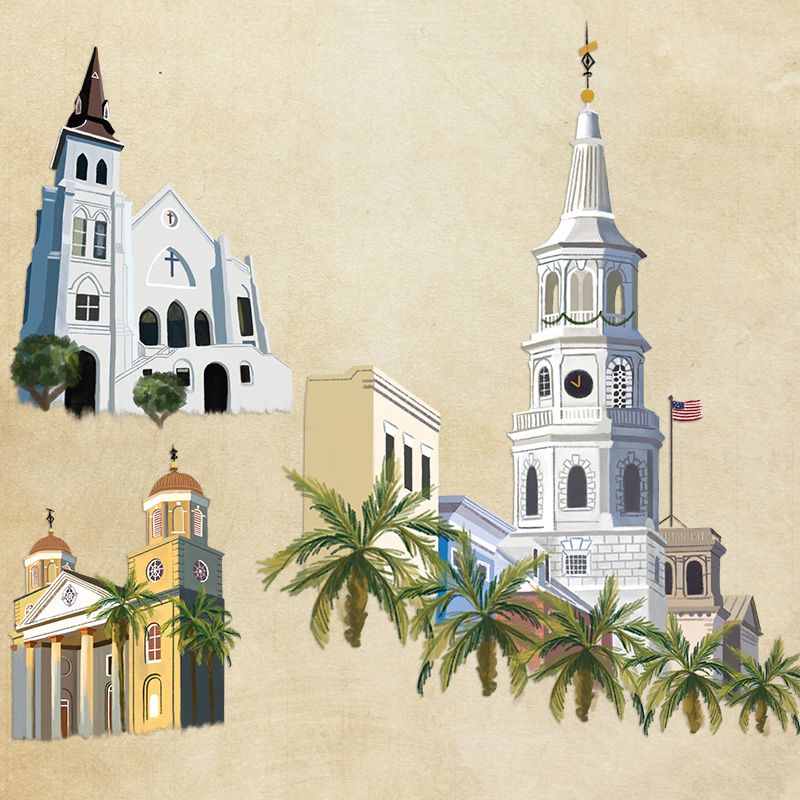

Gothic Grandeur While many of the city’s churches built in the 1700s followed the traditional Wren-Gibbs architectural style, the 1800s saw the introduction of the Gothic Revival style, as seen in the multi-pinnacled French Huguenot Church (c. 1845), designed by Charleston architect Edward Brickell White, and the buttressed, stuccoed brick walls and detached steeple of “Mother” Emanuel AME Church (below), designed by Charleston architect John Henry Devereux (c. 1892).

Chiming Time From 1764, when the four-faced clock in St. Michael’s steeple was installed, until 1946, when the clock was electrified, it was the city’s official timekeeper, with the bells chiming on the quarter hour. Similarly, the clock installed at St. Matthew’s Lutheran in 1901 maintained the time for residents of the Upper Peninsula.

Bird’s-Eye View Because of their height, steeples historically have been used as watchtowers. American patriots used St. Michael’s 186-foot high belfry during the Revolutionary War to guard against enemy assault. It later served as a fire tower for the Lower Peninsula. Likewise, the spires of St. Philip’s Church and St. Matthew’s Lutheran also operated as fire towers.

Wind & Fair Sailing Weather vanes atop steeples function as more than decorative additions. In the days of sail, wind direction often determined whether conditions were favorable for a vessel to leave or enter the harbor. The north tower of the twin-domed First Scots Presbyterian Church (c. 1814) is topped by a weather vane (left), and Swiss-born artist Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774) painted and gilded the elaborate seven-and-half-foot- tall vane on St. Michael’s steeple in 1755.