A beloved children’s Easter story, birthed in Charleston nearly a century ago, tells a most powerful tale

A few years ago, The New York Times Book Review posed a series of questions to Caroline Kennedy about books that she loves. When the topic came to childhood favorites, Kennedy cited one as having “my all-time favorite character”—someone she saw as “a woman who re-enters the workforce after raising a family—who ‘leans in’ and does it all much better” than the men who surround her.

It may sound like the story of an empowered, modern woman, but would you believe the book in question was written in 1939 by a Charleston-born man whose family roots stretched back to the founding of the city?

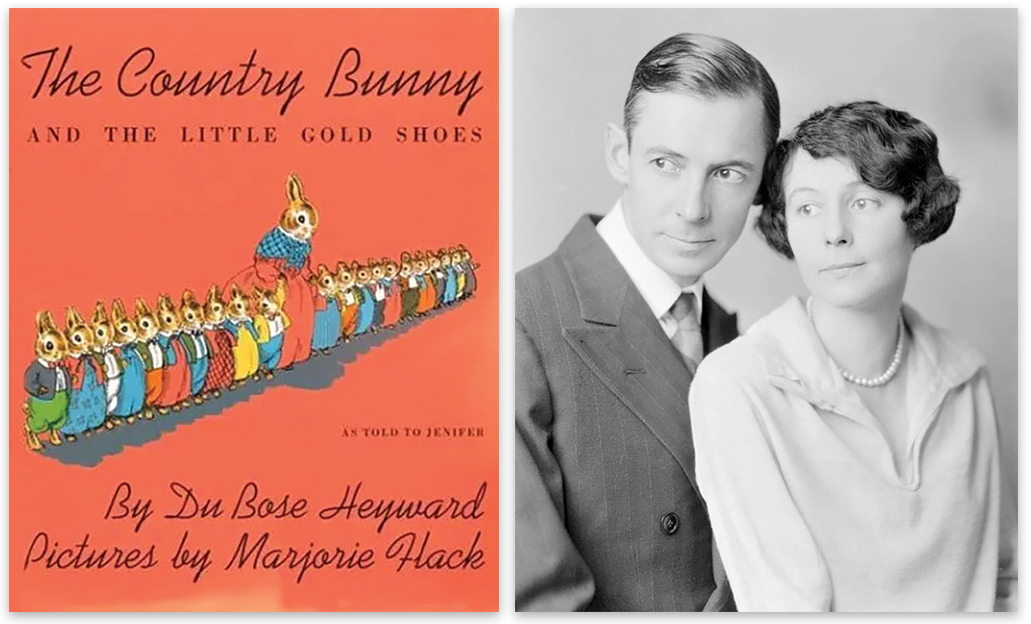

The author was DuBose Heyward of Porgy, and later Porgy & Bess fame. His children’s tale, The Country Bunny and the Little Gold Shoes, was an instant best seller when it debuted, and according to its publisher, Houghton Mifflin, has never been out of print. Heyward would often tell the story of Cottontail—a female rabbit who aspires to be one of the elite Easter Bunnies, delivering eggs to all the little children of the world each Easter Eve—to his young daughter, Jenifer, and was persuaded by his friend (and eventually the book’s illustrator) Marjorie Flack to write it down.

Like all enduring children’s literature, the simple premise of the tale belies a serious message. In this case, it’s a social and ethical lesson wrapped up in a remarkable parable of female empowerment, gender equality, and racial equity.

You see, Cottontail is looked down on by the male rabbits as unworthy of ever attaining her dream, to be one of the five lucky rabbits entrusted by Grandfather Bunny to make sure all the eggs in his palace are in the hands of children by Easter morning. That’s because she has several strikes against her. She is female. She raises a family of 21 baby bunnies (no husband features in the story, except that we know she is married). She lives in the country instead of the city. And, to marginalize her even further, she’s not white: she’s “a little country girl bunny with brown skin” who is “laughed at” by “all of the big white bunnies who lived in fine houses.”

(Left) The Country Bunny and the Little Gold Shoes; (Right) Author DuBose Heyward and his wife, Dorothy, a playwright; after his novel Porgy was published in 1925, the couple adapted it for the stage, which later became the opera Porgy and Bess.

How does Cottontail beat the odds? Collaboration. Lifting up. And instilling a strong work ethic in her progeny: when her children are old enough, they each take on a task to keep the household running—cleaning, sweeping, cooking—as well as providing artistic outlets for the family, developing talents in singing, musicianship, and art.

Grandfather Bunny recognizes her wisdom and kindness as she demonstrates her children’s talents and accomplishments. When Cottontail heroically delivers the last egg to a sick child who lives atop an ice-covered mountain, she becomes his “Gold Shoe Bunny” and rises to the top rank of the Easter Bunnies.

And here’s the kicker: the story originated not with Heyward, but with his mother, Jane Screven Heyward, who knew a thing or two about “leaning in.” Soon into their marriage, her husband died in a horrific accident, and she was left alone to provide for herself and two young children (DuBose and a sister, Jeannie). For a time, she took in washing and mended clothes and did whatever else she could to keep the wolf from the door, until she discovered her true calling: penning poems and stories about the Gullah community. In writing about the Black women who shared her fortitude and optimism, she understood them to be her sisters.

That, in part, is why DuBose came to write Porgy—the novel that revolutionized Southern literature by portraying Black Americans with realism, honesty, and psychological depth—as well as a children’s story that posed the question: must women be marginalized because of their gender, class, or color? In the words of Porgy and Bess lyricist, Ira Gershwin, “It ain’t necessarily so.”

James Hutchisson, emeritus professor of English at The Citadel, is the author of The Rise of Sinclair Lewis, editor of Sinclair Lewis: New Essays in Criticism, and past president of The Sinclair Lewis Society. His most recent book is Ernest Hemingway: A New Life.