In 1682, colonist Thomas Newe wrote his father in London about the new settlement of Charles Town: “The Town which two years since had but three or four houses, hath now about a hundred houses in it, all which are wholly built of wood, tho’ here is excellent Brick made, but little of it.”

Charleston might have remained a town built of clapboard except for one fact: wood burns. After a string of disastrous fires, culminating in the blaze of 1740 that destroyed almost a third of the city, the city fathers finally caught on. They passed a law requiring that all buildings would “henceforth be built of brick or stone.”

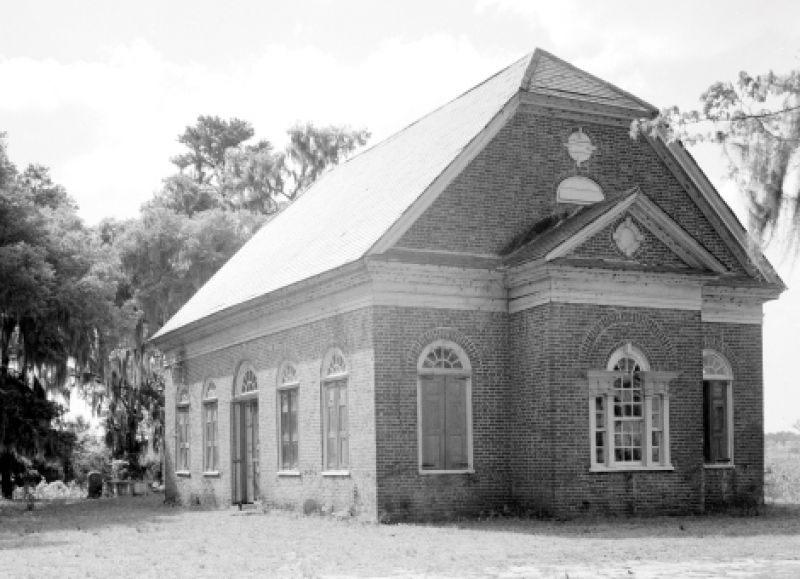

Although the Lowcountry has no natural stone, just beneath the topsoil lies a thick strata of rich, red clay. After the passage of the 1740 law, this clay provided a yield as valuable as pure gold. Almost overnight, brickmaking became a major industry and one of immense historical importance.

Besides clay, a brickyard needed sand to temper the bricks, wood to fuel the baking kiln, and proximity to navigable water to transport the finished product to town. This was a perfect fit for lands along the Cooper and Wando rivers and a windfall for plantations on Daniel Island and in Mount Pleasant where the water was too salty for rice to be grown.

Boone Hall and its appropriately named sister plantation, Brickyard, are perfect examples of the importance area-made bricks had on the formation of the city we know today. Owned during the early 1800s by architect/builders John and Peter Horlbeck, Boone Hall created bricks that built such noted architectural treasures as the Exchange Building, St. John’s Lutheran Church, and the Izard-Pinckney House at 114 Broad Street and also supplied a lion’s share of the astounding seven million bricks it took to build Fort Sumter.

Until the Civil War halted Charleston’s building boom, the millions of bricks produced in the area shaped the city’s homes, churches, buildings, fortifications—even its streets and sidewalks. It is no exaggeration to say that local bricks are the structural backbone behind the wealth of architecture for which the city is famous. Indeed, they are historical proof that Charleston was, quite literally, built from its own ground up.