Behind an imposing Byzantium blue front door in a tropical courtyard off magical Bedon’s Alley is clue number one to the rollicking mind of artist Dr. Richard Hagerty. There, a litany of names of inspired geniuses—Shakespeare, Raphael, Stegner, Rousseau, Bosch, Céline, Colette, Woolf, Rilke, Whitman, Calder, Kahlo, Chagall, Puccini, Dali, among others—are stenciled in a frieze leading down a long hallway of the 18th-century home. They whisper “welcome” to this lair for artists, a creative cauldron of sorts, where Richard and Barbara Hagerty reside—painter and poet, native Charlestonians, childhood sweethearts, and muses married to one another for 42 years.

In this three-story South of Broad manse, Richard and Barbara raised four kids, and as the stroller in the dining room now attests, grandbaby Scout will soon be toddling about, bumping, no doubt, into paintings. They are everywhere. All with the same kaleidoscopic vitality. Each an unharnessed fable, a romping fantasia of dynamic color, whirling geometry, and limbic form. Framed in gold, hung high and low, stacked against walls, propped on top of chests. “And this is just some of them, there’s jumbles of stuff. He’s wildly prolific,” poet Barbara says of her husband, with a wink of understatement.

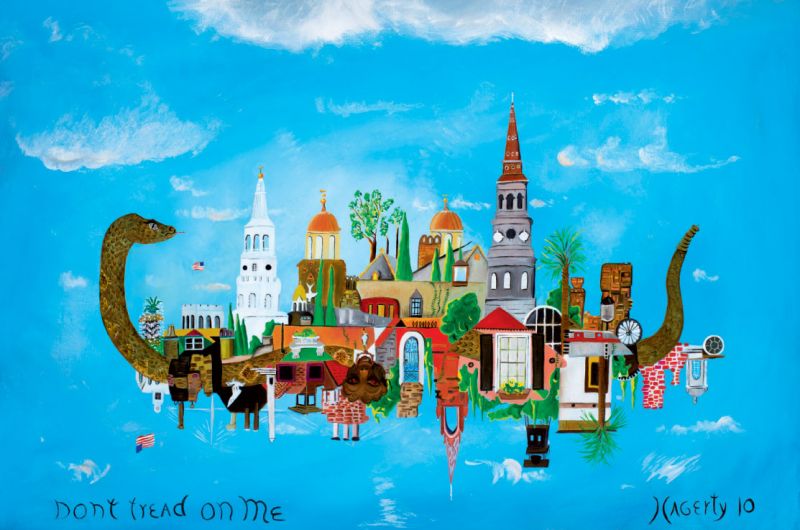

As the retrospective exhibit set to open November 19th at the City Gallery at Waterfront Park makes evident, Richard Hagerty, or “Duke” as he’s better known, is not only prolific, he’s wildly articulate in various media, with his prodigious output over the last 40 years representing an ongoing carnival of the mind. His work is perhaps best known for gracing Piccolo Spoleto Festival posters five different times (1984, 1990, 2003, 2007, 2008)—more than any other artist. He’s had solo exhibits at the Gibbes Museum of Art, the Aiken Center for the Arts, Corrigan Gallery, and Tippy Stern Fine Art, among a dozen others, and has been included in group shows across the Southeast. But despite being a working artist since the mid-’70s, his motivation has never been commercial. For Hagerty, painting and drawing are means of exploring psychological landscapes, traversing those thin, porous borders between the conscious and unconscious, between myth, dreams, and reality.

Surrealism, or “psychic automatism in its pure state,” as defined by French poet and intellectual André Breton, who coined the term in 1924, may be the most fitting stylistic description of Hagerty’s playfully haunting work. But for this accomplished plastic surgeon and lifelong dyslexic, it’s even purer than that. Reading has always been challenging, while “art was a language I understood,” he says.

A BACKWARDS BOYHOOD

The oldest of five, Hagerty grew up on Legare Street in a “typical Irish-Catholic family, with all the good and bad that comes with that,” he says. His Boston-born, Harvard-educated father, Robert, had been a decorated field surgeon with the intrepid First Marine Division in World War II. “Dad was a devoted Marine and developed an intense bond with his fellow Marines during the War, most of whom were Southerners, so he vowed to live in the South,” Hagerty says. Settling in Charleston in 1952, the elder Hagerty became the state’s first plastic surgeon. His wife, Mary—an artistically inclined free spirit from rural Statesburg, South Carolina, who earned her pilot’s license at age 17 and graduated from Duke University School of Nursing (where she was studying when she met Robert during his surgical residency)—became involved in the city’s cultural circles and served as president of the then-Gibbes Art Gallery Auxiliary. Intellectual rigor was integral to the Hagerty family DNA, so when Duke struggled with reading and failed English assignments, “it was frustrating and difficult for all of us,” he says. “It threw me off into a different world.”

More recently, Hagerty began signing his artwork in a hieroglyphic-like backwards script in celebration of his dyslexia, but back then, the disorder was not yet recognized or understood, which resulted in a deep sense of isolation for young Duke. He compensated through hard work and discipline and gained confidence through prowess in science and athletics. “Football saved me,” says Hagerty, a linebacker/defensive end who went on to play at boarding school and as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University.

But equally significant was a brief encounter with the indomitable Laura Bragg, a wide receiver, so to speak, in her own right. Bragg, a Paris-educated intellectual and art historian who counted Gertrude Stein and Alexander Calder among her worldly cadre of friends, had been the trailblazing director of The Charleston Museum (the first female museum director in the country). Hagerty was 12 years old when his mother sent him to Bragg’s house on Chalmers Street. “Miss Bragg, who was ancient at the time, put an art book in my hand, and I’m looking at this painting by Hieronymus Bosch. That changed everything,” says Hagerty, who resonated with Bosch’s chaotic allegorical images and was awed by the artist’s writhing with apocalyptic concepts of sin and redemption—all the stuff that was bubbling up in the mind of this adolescent catechism student.

Though Hagerty doodled as a kid and had a short-lived attempt at an art class (“I just walked out, didn’t want that structure”), he didn’t have serious exposure again until an art-appreciation course in France during a high-school year abroad. Then in medical school during the late ’70s, he says, “things really popped.” Hagerty drew and painted regularly as counterpoint to the restrictive right-brain grind of medical school and residency training, and while studying Carl Jung during a psychiatry rotation, he began sketching his dreams. “It was the first time I connected dreams and drawing—it was a falling-off-the-donkey moment. I’ve been full-on since then,” says Hagerty, whose compositions evolve from symbols and images (such as a recurrent rhinoceros) that populate his nocturnal musings.

The Dandy Warhols Philosopher

“Full-on” means drawing, painting, studying, and note-taking during every spare moment of a chocked-full family life and medical career, including the nine years that Hagerty served as chair of MUSC’s plastic surgery department and the four-year term (1996 to 1999) on Charleston City Council. That’s not to mention the eight rugged volunteer trips he’s taken to Cambodia, Vietnam, Peru, China, Haiti, and Honduras to teach surgical techniques and perform cleft-palate surgeries. “This kind of work is so different than being a tourist,” says Hagerty, who ravenously immerses himself in studying a country’s culture and history before traveling and only participates on trips where teaching is the focus. “I come back with journals full of notes and sketches that I then incorporate into my paintings,” he adds, opening up a printer’s file drawer in his airy second-floor studio (“a drawing room that’s truly a drawing room”) to reveal a collaged trove of notebooks—“my source,” he says.

That source has fueled ample artwork. The City Gallery exhibition that runs through December includes only a small portion of some 250 images and objects (painted mandibles are a Hagerty favorite) catalogued by Barbara and art historian Roberta Sokolitz, who curated the retrospective and wrote an introductory essay to the accompanying book, American Surrealist: The art of Richard Hagerty (Evening Post Books, 2015). This evocative compilation of 40 years’ worth of work will likely leave some viewers asking two questions: If there’s that much swirling around in his head, then what, pray tell, am I stifling? And secondly, and more practically, how does Hagerty do it all?

“Well, I don’t watch much TV,” the boyishly rumpled doc deadpans. “And I don’t spend a lot of time worrying about how I dress,” he demurs (admitting as an aside that his son, Richard, describes him as “a homeless person on vacation”). Plus, he repeatedly notes, he’s blessed with his “muse from day one,” speaking of his wife and creative partner. “Barbara’s a writer and lover of words, and I’m constantly using the wrong words. It’s a joke, really, how she could be married to me. But we’re both artists and have so much respect for each other with the process,” he says, admitting that Barbara probably gets the short end of the stick. “I do drive her to poetry readings; I’m literally the chauffeur,” he adds. “But I depend on her more for criticism for my art; she can tell me when a painting is finished or not. She never patronizes me, and she’s never censored me. Probably should,” he laughs.

Indeed it’s the rambunctious interior life, not exterior appearances, that interests Hagerty. “He has high inner standards; there’s a real seeker in there,” notes Barbara, who marvels at her husband’s stamina for extended meditation retreats and ongoing Aristotelian-type dialogue and self-directed study sessions of heavyweight philosophers (Wittgenstein, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, The Buddha, Schopenhauer…) that he and his good friend and tennis partner, the writer Gary Smith, have maintained for years. Despite the dyslexia, Hagerty is a voracious reader and consummate student. He’s curious about quantum physics and listens to opera and Mahler while he paints. “…And The Dandy Warhols, the Mahler of the rock world,” he adds.

Pouring himself in

Don’t let the endpoint connotation of a term like “Retrospective Exhibit” fool you. After recently stepping down from his medical practice, Hagerty is not so much retiring as retooling. “I’m just shifting my center of gravity,” he says, acknowledging a promise he made to himself five years ago that he’d paint full-time, “while I still have all my faculties—mental and physical.”

Way back when he was a young artist and husband in the midst of his surgical residency at Emory University in Atlanta, one of his mentors and residency directors recognized Hagerty’s dual passions and talents—art and medicine—and encouraged him to take a year off and just paint. “I tried it for about a week, but couldn’t do it. I realized you need two things to be a good artist: something to say; and a vocabulary to express it. I just didn’t have the life experience yet,” he says. “But now I can put all my energies into it. Now I do have life experience. I’m not retired at all, I’m pouring myself into this.”

A Surreal Celebration

The Exhibit:

“Richard Hagerty: American Surrealist” is on view at the City Gallery at Waterfront Park from November 20, 2015 until January 10, 2016. The opening reception, which is free to the public, is Thursday, November 19 from 5-7 p.m. Hagerty will be giving two artist talks: Sunday, December 13 at 2 p.m. and again on the final day of the show, Sunday, January 10 at 2 p.m. Both are free and open to the public. The City Gallery, located at 34 Prioleau Street, is open Tuesday-Friday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Saturday and Sunday, noon to 5 p.m.

The Book:

An accompanying monograph (i.e. gorgeous coffee-table book) published by Evening Post Books features more than 250 of Hagerty’s works, including 175 color reproductions as well as black-and-white sketches and photographs. For American Surrealist: The art of Richard Hagerty, art historian Roberta Sokolitz wrote an introductory essay, and writer Gary Smith penned an insightful and entertaining interview with his friend, the artist. As fellow artist Jonathan Green blurbs on the book jacket, “Richard Hagerty’s surrealist paintings reflect symbolic expressions of a genius who was born already knowing how to paint. Through self-discipline and meditation, he has been able to dip his brush into his collective unconscious genetic memory to create images that must be more than 30,000 years old.”