The once largely inaccessible waterway is soon to welcome South Carolina’s newest—and largest—state park

I had lots of questions about snakes in the weeks before loading my canoe with camping gear, a banjo, and a stocked cooler to float 106 miles of the Black River. There were also a few about alligators, wasp nests, mosquitoes, low water, high water, and the frequency of dry riverbanks suitable for camping.

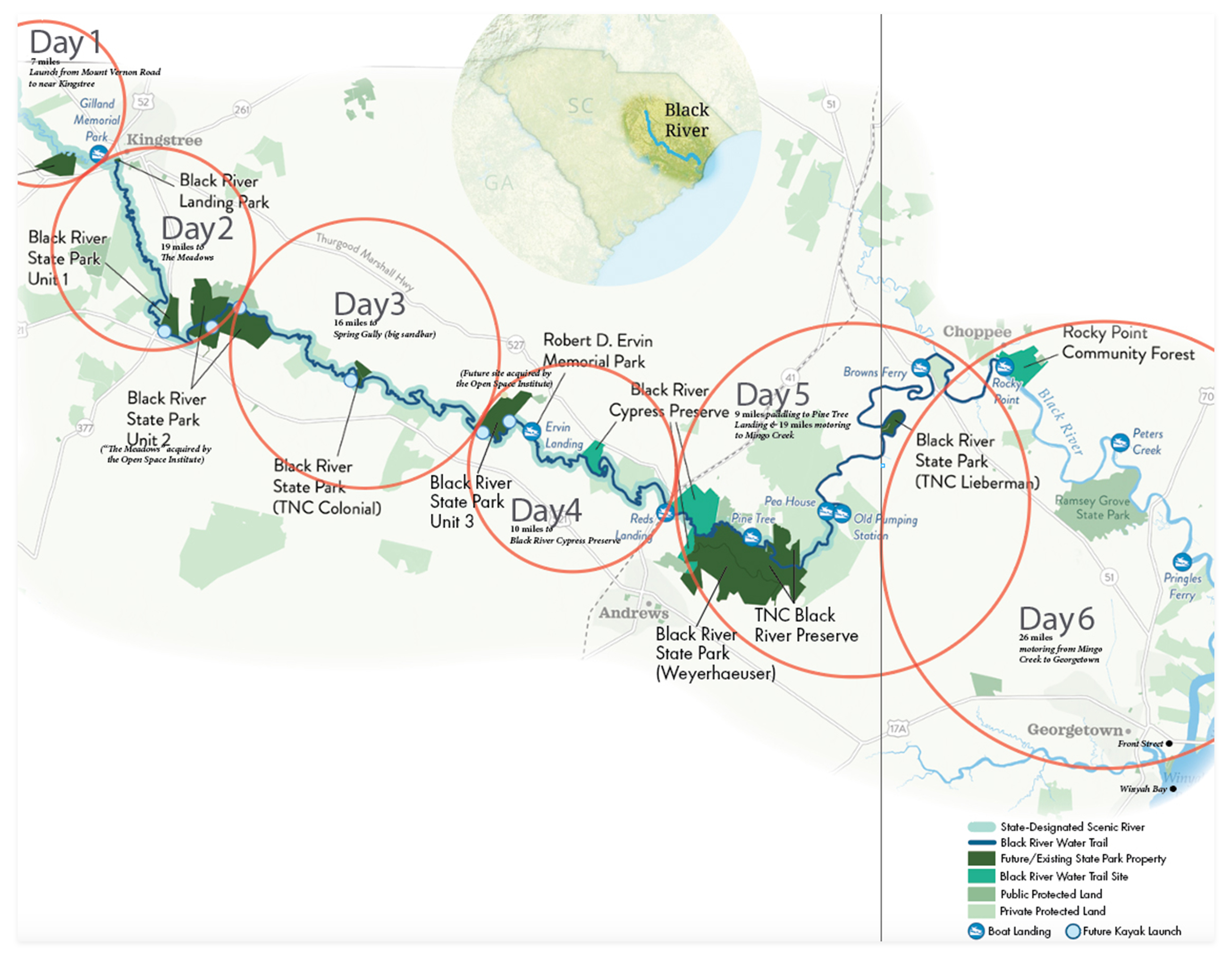

Exploring what is soon to be South Carolina’s newest (and largest) state park won’t be as perilous for most visitors. But I wanted to experience the entire river, including all eight sites of the soon-to-open Black River State Park. That meant paddling sections that see little-to-no human visitors each month and coordinating a multiday trip without the conveniences of secure parking, private shuttles, and knowledge of current conditions from recent trips.

In the end, the only real threat our foursome of confident outdoorsmen faced was an active lightning storm that struck all around us in the summer afternoon heat. We squatted in the lightning position, holding our heels together and exchanging nervous glances. A few hours later, watching a thousand lightning bugs dance to a chorus of tree frogs, we toasted our good fortune: to be alive, in this moment, on the wildest river in the Lowcountry.

The Roots of Preservation

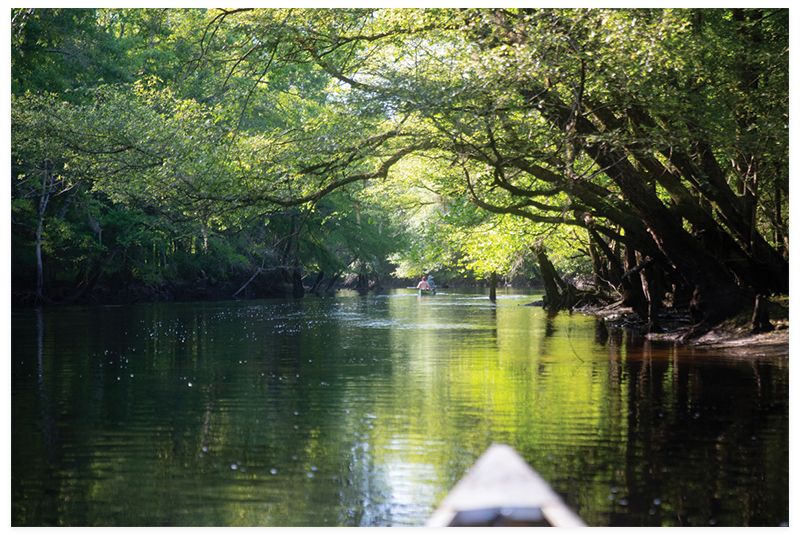

The Black River meanders from Bishopville to Georgetown, becoming (mostly) navigable to kayaks and canoes around Kingstree (an hour-and-a-half north of Charleston). Forty miles separate the two public access points in Kingstree and Andrews, the river’s two primary towns. Boat traffic—mostly jonboats with electric motors used for fishing—tends to stick within a mile of these landings, leaving most of the river quiet for kayaks and canoes. Those willing to portage through mud and fight their way through thickets of branches can experience true solitude.

The lack of access, along with lengthy stretches of privately owned riverfront land, has helped preserve the Black for generations as the Lowcountry’s population swells. The river rivals the Edisto in its beauty and appeal to paddlers, yet it’s largely off the radar.

But not to Maria Whitehead. The Florence native and director of land for the Southeast at the Open Space Institute (OSI) grew up visiting the river via her family’s rustic camp on its tributary, Mingo Creek, upriver from Georgetown. She’s enjoyed decades of peaceful paddling, following swallow-tailed kites deep into the swamp before carefully retracing her turns.

When International Paper began selling off its riverfront landholdings, Whitehead felt both the threat of future development and an opportunity for conservation. Because most locals have only seen small portions of the river near the landings, she saw increased public access as the path forward. “How do people choose to protect something they can never experience?” she asks. “The big-picture strategy was to find a public partner and steward that was willing to own and manage the land.”

In 2019, Whitehead pitched the state’s Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism on the idea of a riverine park with multiple locations, offering safe parking for put-ins and takeouts, campgrounds, interpretive centers, hiking trails, boardwalks, and other amenities. Only half-a-decade and a global pandemic later, the first of eight already secured state park properties will open to the public by year’s end. Together with the Nature Conservancy, South Carolina State Parks, and private donors, OSI has acquired 12,000 acres in five years. Also significant is its location in Williamsburg County, one of the only counties to not have an easily accessible state park for its residents—and one of the least economically developed. “This creates business opportunities in a region where even modest economic gain can be a big deal,” says Whitehead, citing the need for canoe rentals and shuttles, restaurants and stores. Kingstree has already rebranded itself as the “Crown of the Black River,” a phrase now printed on streetlight banners.

I wanted to experience the Black River, but pulling together a trip before all of the park amenities have opened proved difficult. Would the upper river be navigable? Would I have dry land to camp? Where can I get off the river to find help if I’m bitten by a cottonmouth and don’t have cell service?

Whitehead put me in touch with Dr. Louis Drucker, a retired dentist in Kingstree and volunteer riverkeeper on the upper Black. She also offered her family’s cabin on Mingo Creek as a pre-trip staging point and the final night’s accommodations after five days of paddling and camping. Brooks Geer, co-owner of the Sewee Outpost, volunteered a shuttle to the put-in ahead of joining the expedition for the second half, including a motorized 50-mile run in his 17-foot center console Scout from Pine Tree Landing to Georgetown, once the river becomes wide and tidal and more difficult for canoes. Finally, fellow Folly Beach dad, Ryan “Co” Coverdale and his buddy Ryland Fox signed up to join me for the whole adventure.

Day 1: (left to right) The author’s 16-foot fiberglass canoe; moments of still air create surreal reflections in the swamps along the river; Co prepares dinner for the crew.

Day 1

Our plan set, we drive 13 river miles north of Kingstree on a steamy Wednesday morning. As we haul gear and canoes down the path to the river’s muddy bank beside Mount Vernon Road, a man wearing an NRA hat appears through the trees and offers to help. He kindly gives us his number and offers to unlock the gate in advance to make our put-in easier for a future trip. It’s a welcome introduction to the locals.

The river this far up is narrow and winding. A single downed tree could completely block our passage. We navigate tight turns in the first mile and fallen trees that force us to lie down in our canoes or carefully step over branches while the boats pass underneath. I carry a handsaw and reciprocal saw, cutting our way through a couple of thick branches and completely unloading the canoes to haul them over a muddy bank a few turns later. The threats of venomous snakes on downed trees—and wasp nests in overhanging willows—are always top of mind.

On this seven-mile day, our only other human encounter is a man sitting along the river on a bucket, wetting a line. “What do you catch here?” I ask. “Bream, but you can pretty much catch anything in this river,” he replies. We tip our hats and float downstream.

A few hours before sunset, we reach an inviting creek that meanders off to the side of the river, a future oxbow lake that’s still got some flow. Its shallow, sandy bottom invites exploration, and we quickly realize we’re on a small island. Deer, raccoon, and bird tracks dot the sandbar, but the muddy ground around it is pockmarked with holes we assume were made by wild pigs. We dub it “Pig Island” and decide to take our chances on nocturnal visitors. (Two days later, when I round a bend and disturb a sounder of more than 20 hogs, some 200-plus pounds each, I understand that such an encounter in our campsite could have been alarming.)

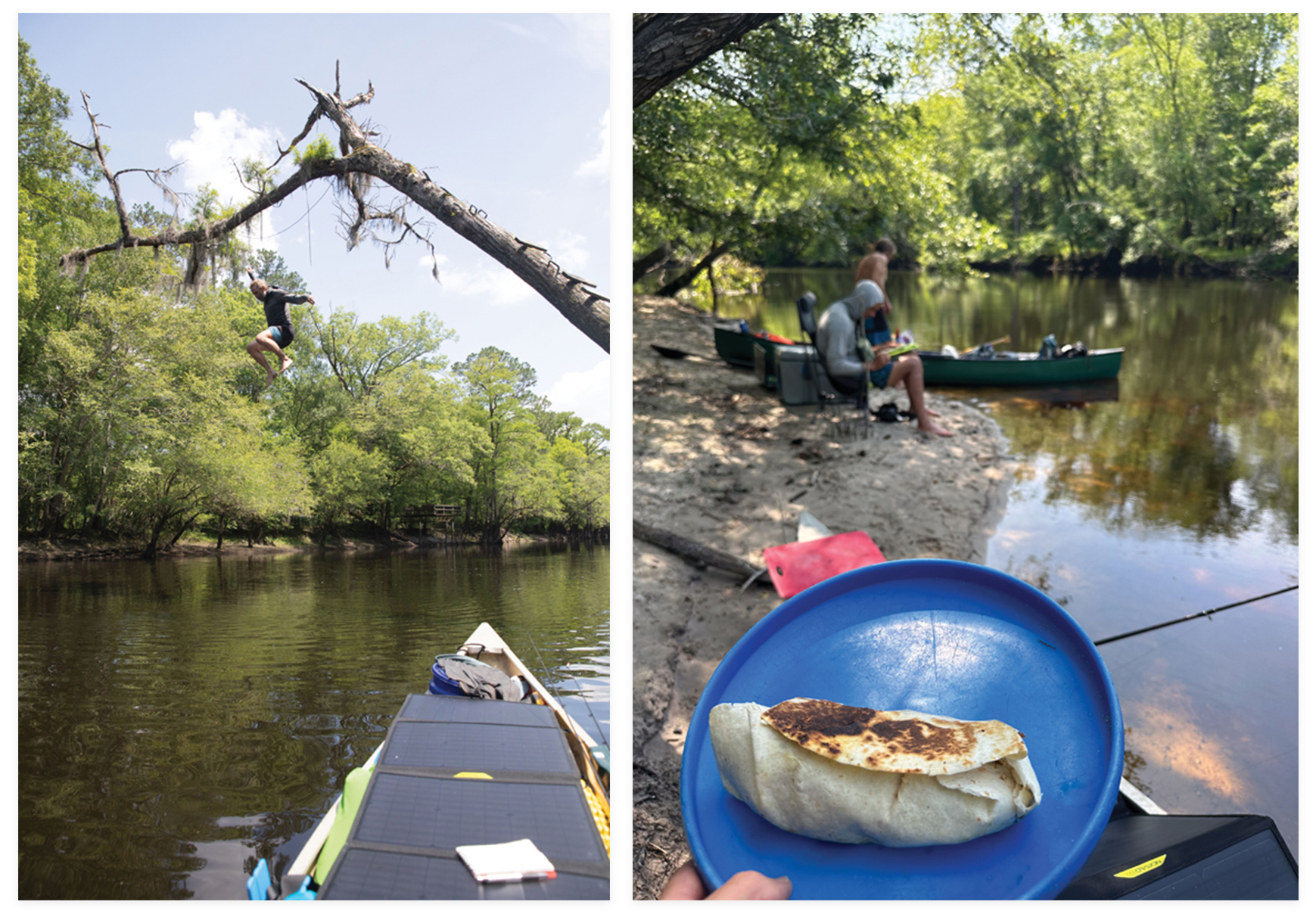

But on that first night, we have no cares. Co serves as camp chef, spoiling us with stir fries, stews, and hearty wraps all week. We eat chili around a small fire and revel in the quiet of the starlit night.

“We want to preserve that feeling that you’re the first person to ever experience this.” —Nick Wallover, Open Space Institute park project manager.

Day 2: Paddling just south of Kingstree with Dr. Louis Drucker, the town’s volunteer riverkeeper.

Day 2

Drucker joins us for the paddle from Kingstree to The Meadows, the state park site that opens this fall. En route to meet him, we cruise past some of the trip’s finest sandbars, allowing ourselves one quick break from the morning heat for a heavenly dip. Drucker grew up in Kingstree, and I soak up his encyclopedic knowledge as he points out starling nests under the Main Street bridge and the beautiful but invasive South American scarlet sesban that’s overtaking many of the river’s banks. He spots kingfishers, snowy egrets, and great blue herons, before mentioning that if we see a short, bearded man with a French accent, we should paddle faster.

“Frenchy” is a Kingstree legend. The diminutive man arrived from Charleston on a train in the 19th century. He repaired umbrellas, had a large dog, and slept outside along the river. “One day, someone realized they hadn’t seen Frenchy lately, so they went looking and found his big ol’ dog torn to shreds,” Drucker recounts. “They finally found a skull and an arm.”

We still haven’t seen an alligator, but given how often the river splits to flow quickly through the forest or slowly meander over a sandy bottom to the side, it’s easy to see how Frenchy could have gotten hopelessly lost. We forge ahead, covering 16 miles on our way to meet Nick Wallover, OSI’s park project manager, just upstream of the Meadows site. “This is an incredible generational opportunity for our state,” he says of the Black River State Park. “In the past, these communities relied on the Black River for their economy, transportation, and food, but they’ve lost access to it. The river is a public trust resource.”

In addition to kayak and canoe launches, the project also allows for Native American tribes, including the Catawba, Wassamasaw, and Pee Dee, to once again access ancestral land. The Chicora tribe plans to host powwows at the Rocky Point site. In that vein, the park’s development strives to maintain the wild experience we’re enjoying now. None of the park sites will include additional landings for motorized boats. “We want to preserve that feeling that you’re the first person to ever experience this,” Wallover explains. But you won’t have to travel 100 miles like we are. The Meadows site alone, for example, includes four miles of river frontage, allowing for a leisurely day paddle with a put-in and takeout on the same property.

Wallover mentions recent grants, including $4.6 million to build paddling-oriented infrastructure at the various park sites, and another that will provide a mobile swimming pool and swimming instruction so area residents can confidently visit the river. If OSI’s ability to navigate red tape and acquire property in just five years seems incredible, it is. “I call it ‘Maria’s Magic,’” says Drucker. “She’s able to step in and make progress where others haven’t.” Wallover agrees, “It’s remarkable. This is her legacy.”

Day 3: (left) South of Kingstree, Co takes his chances with the rotting planks held in by rusty nails to make a splash; (right) seared burritos for lunch from chef Co.

Day 3

I spy a bug in my tent that I’ve always called a “mosquito eater.” But then I realize it is a mosquito—it’s some species bigger than any I’ve ever seen before. I’ve experienced mosquito insanity from Alaska to the Everglades, but I’ve never seen bloodsuckers this big.

Bugs are one of the trade-offs for adventure. We opt for the bypass around a sketchy, swift-water shortcut through the forest, and it turns out to be the prettiest quarter mile of the trip. The water is a foot deep, with white sand between banks of floating flowers. We’re miles from a road, and the only noises are songbirds and cicadas harmonizing with the breeze rustling the willow trees. It’s the kind of paradise that could fool the Spanish into thinking they’d found the Fountain of Youth.

Just ahead, an island of aquatic plants requires a tight, 90-degree turn to the left, then another sharp turn to the right. I miss the maneuver in my overloaded canoe and have to back-paddle to realign, pulling myself into the floating vegetation. “This is where a snake would be,” I think. And there she is, a foot from my hand on my paddle. I react, pushing my boat away, catching my fishing rod on a branch, and snapping off the tip.

It’s not our first snake. The day before, we passed under a tree with cut two-by-fours nailed into the trunk, allowing for a 20-foot drop from the canopy into the river. After Co and Ryland each took a turn, I paddled up to the approach and a five-foot banded water snake surfaced at the first step. I then realized that they’d been with us the whole trip. Your eyes just have to learn to see them. Slow down, and wildlife is everywhere.

When we reach Simms Reach Road, Brooks is there with his father, George, who volunteered to shuttle him up and bring us the Scout two days later. Brooks spends the first hour fidgeting with his canoe, trying to get everything just right, and I recognize myself two days earlier, before I’d settled into river time.

We pass a wide swamp on the left with a grassy sandbar on the right bank. It’s already 5 p.m., and the swamp would offer a fun moonlit exploration after dinner. But Brooks is acclimating, and we opt to press forward and take our chances on finding another campsite. By 6 p.m., the rain starts. The next sandbar we’re sure about is still three river miles ahead, but we know it’s a big one, on a turn of the river locals call “the hammerhead.” The last mile has no turns—just a straight shot on the widest river we’ve seen yet, into a head wind under bands of driving rain, with occasional lightning. We paddle hard, reaching the sandbar just before dark. By 10 p.m. the rain stops. We set up camp on a sandbar that stretches more than 1,000 feet around a bend and fill our bellies before drifting off to sleep.

Day 4: (left) Ryland kicks back in a canoe built for two; (right) the river splits into multiple channels throughout its course, offering opportunities to explore—and get lost.

Day 4

Everything is wet, so we take the morning off. It’s sunny, and this gargantuan sandbar is perfect for a lazy morning reading and playing banjo while our tents and gear lay out to dry. We’re in high spirits as we ease around our first turns after lunch, approaching the point where George Geer warned us that the river will appear to continue straight, which caused him to get lost on an evening over six decades ago. The centuries-long process of a river changing course is underway. We take the small channel to the right, entering another stretch of swift, narrow river; tight turns; and a complete lack of human presence.

Halfway through this four-mile stretch, a storm overtakes us. I actually have a bar of data service. It takes a few minutes, but I pull up the radar. It looks as bad as it sounds around us, with thunder claps every 30 seconds within a mile or two. We find a small sandbar, separate from each other, and squat in the lightning position. It’s all we can do but hope and pray.

Day 5: (left) An ancient cypress tree along the riverbank; (right) Exploring Mingo Creek, about 30 miles north of Georgetown.

Day 5

It’s our last day in canoes, on a stretch that includes “the narrows,” so-called by Andrews residents for the contrast between these few miles of fast river and the broader, slower, straighter water that’s becoming the norm this far downriver. The cypress trees are getting bigger—groves as big or bigger than any in Congaree National Park. The root systems of some trees are wider than my 16-foot-long canoe. Trees like this didn’t survive the logging of the 19th century in places that are easy to get to.

In five days, we’ve seen about two dozen people, either on their docks along the few stretches of river with homes or fishermen near the landings. But as the river widens, we approach a flotilla of boaters, anchored together for a Sunday afternoon party. At Pine Tree Landing, there’s a family swimming at the boat ramp—kids with goggles, a man with a rattail in an inner tube. They ask where we’re from. Charleston may as well be New York City here. “Have you got rivers like this down there?” the man asks. They’re friendly enough, but it’s a jarring transition after five days of silently following the river’s flow. I’m not ready for reentry, let alone small talk.

I paddle around the corner to finish my stash of boiled peanuts. The four-nut and three-nut pods are long gone—it’s mostly one-nut shells at this point. I cast my beetle spinner and survey my rig. This canoe has become my home. I’m feeling nostalgic for this very morning as we load our gear into Brooks’s boat. But 30 minutes later, as we cruise the wide river under a kettle of kites turning loops overhead, I’m back in the zone. Cold beers await at Mingo Creek, and we’re all smiles. It’s the magic of the journey, and tomorrow we continue to the ocean.

Day 6: In search of beers and a hearty meal along Georgetown’s waterfront.

Day 6

Maria’s brother, Weaver Whitehead, makes us feel right at home at Mingo Creek. We’re eating well: venison burgers courtesy of Brooks for dinner, followed by eggs, bacon, and biscuits from the Sewee Outpost before setting out on Monday morning. Everything about the river has changed. It smells salty, like home again, as we motor toward the sea. We’ve seen fewer than 100 homes in the first 70 miles, but now we pass stretches with big houses and docks along high bluffs.

Houses give way to centuries-old rice dykes and then salt marsh as we approach the confluence with the Little Pee Dee River. From there, it’s a choppy few miles around the bend into Georgetown Harbor. We walk the waterfront, order a feast at Root on Front Street for lunch, and try to wrap our heads around the adventure we’ve just had.

A State Park’s Journey

Rivers offer an extraordinary kind of journey in our world of planes and interstates. The to-do list each morning is short: make coffee, break camp, head down river. The day’s decisions are equally simple, but often difficult. Stay the night at this perfect sandbar that we’ve found an hour or two before we were ready to stop, or head down river to get a few more miles in, taking our chances? >>READ MORE

How to Explore the Black River

The Black River is historically inaccessible, flanked by private land with the two primary landings separated by 40 miles. That’s changing with the gradual opening of the Black River State Park, which will offer at least eight additional places to securely park a vehicle... >>READ MORE

There are two primary locations opening this year for day trips.

The Meadows:

This 1,276-acre property is the state park’s largest and includes four miles of river frontage and two landings. There are restrooms and secure parking (with tent and RV campgrounds in the works). Two cars allow for a quick shuttle and a leisurely two-hour paddle, or come solo and run the shuttle with a bicycle on the well-graded dirt road between the landings.

Pine Tree Landing:

Just upriver from this landing are many of the river’s largest cypress trees, accessible via kayak or canoe with an out-and-back paddle. Just upriver, a throw-in on Lester Creek, within the narrows at Black River State Park property (opening early 2025), offers a second put-in option. For a longer one-way paddle, start north of Andrews (along Highway 41) at Pump House Landing, dropping a shuttle car at Pine Tree for your takeout.

Supplies & sustenance

Infrastructure to support the park is under development, but some existing businesses offer last-minute gear and hearty post-trip meals.

Brown’s Bar-B-Que, Kingstree:

Get your fill of ribs, pulled pork, and mac and cheese at this buffet just north of town. 809 N. Williamsburg County Hwy., Kingstree; destination-bbq.com/stores/browns-bar-b-q

Cooper’s Country Store, Salters:

Along SC-377 half-a-mile south of the river, Cooper’s is one-stop shopping, from local sausage to bait-and-tackle to a barbecue lunch buffet. 6945 Hwy. 521, Salters;

destination-bbq.com/stores/coopers-country-store

Sewee Outpost, Awendaw:

On your drive up Highway 17, stock your cooler and pick up gear like dry bags, a lightweight raincoat, or a new paddle. Don’t forget a pack of biscuits for breakfast or river snacks. 4853 N. Hwy 17, Awendaw; seweeoutpost.com

Web Extras:

Scan the QR code to see more photos of this adventure and watch a video about the creation of the Black River State Park.