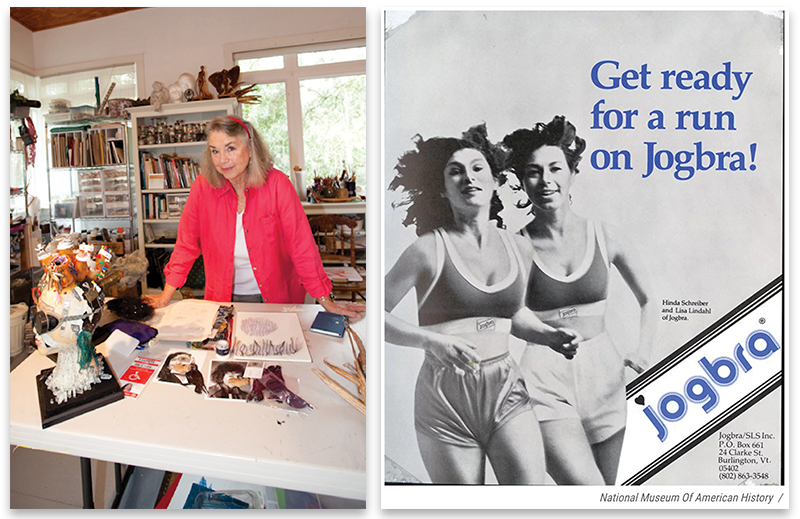

(Left) Sports bra inventor Lisa Lindahl in her Wappoo Heights home studio, where she now devotes her time to creative pursuits; (right) Lindahl and her partner Hinda Miller served as Jogbra’s first models.

WRITTEN BY Melissa Delaney

The Jogbra story starts in 1977 with a few extra pounds. Lisa Lindahl was an aspiring artist, taking classes at the University of Vermont (UVM), working as a secretary, and floundering in a lackluster marriage. The 28-year-old had never embraced fitness since her grade school gym classes, and her sedentary lifestyle led to her first experience with weight gain. A friend told her to run a mile and a quarter three times a week to lose the weight, and she got hooked. “This was the beginning of the fitness revolution, and jogging was the thing,” she says.

One problem. “I’ve always been amply endowed,” and bras at the time were not designed for comfort, Lindahl explains. Her sister, Victoria Woodrow, had also taken up jogging, and the two commiserated. “Why isn’t there a jockstrap for women?” Woodrow joked. “Same idea, different part of the anatomy,” Lindahl agreed. They laughed, but after the call, Lindahl couldn’t get the idea out of her head.

“I wrote down all the things it would need to do,” she recalls. Straps that wouldn’t slip off. No hooks or eyes. It shouldn’t chafe. It should minimize breast movement and be sweat friendly and supportive. She remembered a jogging friend who would whip off his shirt and tuck it into his shorts on hot summer days. “I was so jealous!” she says. “I thought, what if it was actually modest enough, like a swimsuit, that a woman could take off her T-shirt, too?”

Lindahl was onto something, but she fared worse in her eighth-grade sewing class than she did in gym. Her classmate Polly Smith, however, got an A+ and went on to become a costume designer. As fate would have it, Smith was renting the guest room from Lindahl and her then-husband, Al, while creating costumes for the Champlain Shakespeare Festival at UVM.

The duo set out to design a prototype, but nothing worked. One day, while they experimented in Lindahl’s home studio, Al came in with a jockstrap pulled over his chest. “He said, ‘Hey, ladies—here’s your jock bra,’” Lindahl recalls. Between guffaws, she made him take it off, fitted the cup over her breast, and started jumping up and down. “I said, ‘Polly, this actually works!’

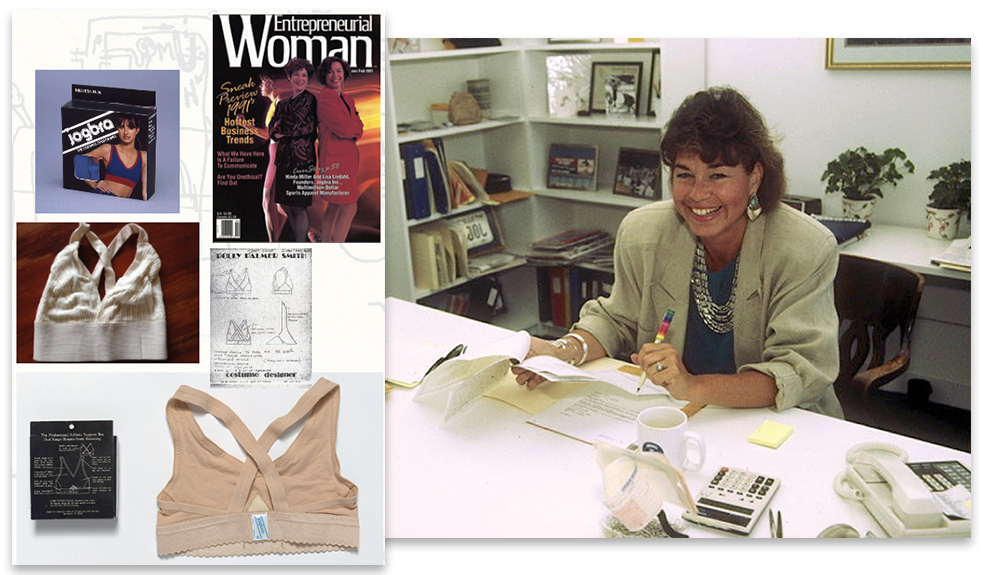

(Left) The “Jock Bra” prototype and Polly Smith’s sketches of it; a collection of Jogbra materials are in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History; (right) Lindahl (pictured above in her Jogbra office, circa 1990) and her partners carved out a niche as the first women-owned business in sporting goods, transforming and fueling the bra industry for decades to come.

Smith sent her assistant, Hinda Miller (then Schreiber), to buy two jockstraps. Smith cut them in half and sewed them together. It was the first cross-back bra, and it went over the head with no hardware. Miller was intrigued. “She went running with me, her running backwards to see how much I was moving,” recalls Lindahl.

They had the engineering down, but the fabric was terrible. Smith went to New York City and found a new cotton Lycra fabric from DuPont. “It was perfect,” Lindahl says. Miller, who went on to teach a costume design class at the University of South Carolina in the fall, found a mom-and-pop manufacturing shop in Columbia to make the bras, and her father, Bruce L. Schreiber, loaned them $5,000 for their first run, followed by another $25,000 personal equity loan that they repaid monthly with 10 percent interest.

Lindahl insisted that the jock bra—later called “Jogbra”—wasn’t lingerie. It was athletic equipment. “The bra industry—pardon the pun—had been flat for over a decade,” she explains. “My generation was burning their bras.” Sporting goods stores, conversely, were on the rise. They were the first women-owned business in sporting goods during the second-wave feminism era, just five years after the passage of Title IX, giving women equal opportunities in sports in higher education. “It was the right product at the right time,” Lindahl notes.

Smith helped with the business, but she prioritized her career as a costume designer and went on to become an Emmy-winning designer for The Muppet Show and Sesame Street. Lindahl and Miller ran Jogbra until 1990, then sold it to Playtex Apparel for an undisclosed amount, though they stayed on, Lindahl for another two years and Miller for seven. Soon after, Sara Lee Corporation bought Playtex and shifted Jogbra to its Champion division. “If running a business got me an MBA, selling a business got me a Ph.D.,” Lindahl says.

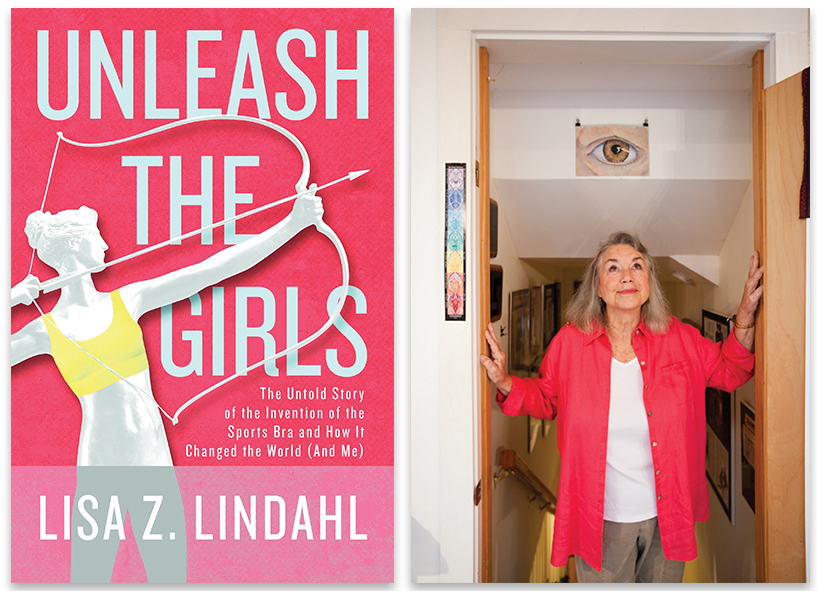

Despite its success, the business took its toll on the women. Lindahl began therapy after she left. “There was betrayal and competition,” she says, noting that she and Miller didn’t speak for years. She wrote about her challenges and “evolving understanding” in her 2019 memoir published by Ezl Enterprises, Unleash the Girls: The Untold Story of the Invention of the Sports Bra and How It Changed the World (And Me).

Soon after leaving Jogbra, Lindahl and her second husband bought a house in Edisto and spent 10 years splitting their time between South Carolina and Vermont. “I had gotten the hell out of everything,” Lindahl says. “I was back in my art studio trying to paint and write.”

But in 2000, Lesli Bell, a Burlington physical therapist who learned that the inventor of the sports bra lived in her town, contacted Lindahl to help her create a bra for breast cancer survivors suffering from lymphedema, swelling in the chest and back. Together, they invented the patented, FDA-approved Bellisse Compressure Comfort Bra. She and Bell ran the business for five years before licensing sales and manufacturing to another company.

Lindahl was thrilled to finally be able to focus on her art, which she saw as her true calling. After her second divorce in 2012, Lindahl bought a house in West Ashley’s Wappoo Heights with an entire floor of studio space.

Lindahl wrote about their experiences starting and running the company in her 2019 memoir, Unleash the Girls.

“One of the reasons I left Vermont was that I was really tired of being introduced as ‘the Jogbra lady.’ I felt like I was so much more,” she says. “But I kept getting attention for the sports bra,” Lindahl says. And she still does. In 2017, ESPN produced a documentary honoring the 40th anniversary of the sports bra. A year later, Runner’s World magazine called it “the greatest invention in running,” which flummoxed Lindahl, who thought her work on the board of the Epilepsy Foundation of America was far more important. “I had no idea about the significance of the sports bra,” she says. “To me, I was just running a business, trying to earn a living.”

The original Jogbra materials are in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and last spring, Lindahl, Smith, and Miller were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, where Lindahl began making amends with Miller and grasping the value of their work.

After years of downplaying her not-so “little mail-order business,” the recognition helped her frame her career in a new light. “I got it,” Lindahl says. “This is really empowering for a lot of women. I finally came to embrace this as my legacy.”

Revolutionary: Watch ESPN’s documentary on the Jogbra.

Revolution: A History of the Sports Bra from Mickey Cevallos on Vimeo.

Images by Mira Adwell & courtesy of Lisa Lindahl & Smithsonian National Museum of American History