These intrepid sisters broke gender barriers at the College of Charleston, reformed public school curriculum, and worked to get the 19th Amendment ratified

The Pollitzer story begins, like many family sagas in the South, at the end of the Civil War. Its scion, Moritz Pollitzer, however, was different from his peers. The Austrian-born, immigrant Jew was a merchant, who had moved to Beaufort from New York to take up the cotton business, stepping into something of a vacuum—and therefore a great business opportunity—left by plantation families who had fled the area during the Federal invasion of 1861. In some parts of the South, Moritz may not have been able to become the success that he did. But in South Carolina, and particularly in Charleston, where his son, Gus, moved the family business in the 1880s, Jews were not only welcomed but became prominent influencers in the community.

A strong Jewish presence had existed in the city for 200 years—since the late 1690s, when the colony had established itself as a haven for ethnic minorities fleeing religious persecution. As with others welcomed in the Holy City, Jews were given full citizenship rights—not the case elsewhere. By the time the Pollitzer family began its rise, Charleston had the largest, most prosperous, and probably the most cultivated Jewish community of any city in North America.

Perhaps it was, in part, this affirming environment of openness, of welcoming change, that made Gus’s children so devoted to public service. They committed their lives to causes on behalf of people whom America had left out, speaking for the oppressed and the marginalized. And in doing so, they helped to change a nation.

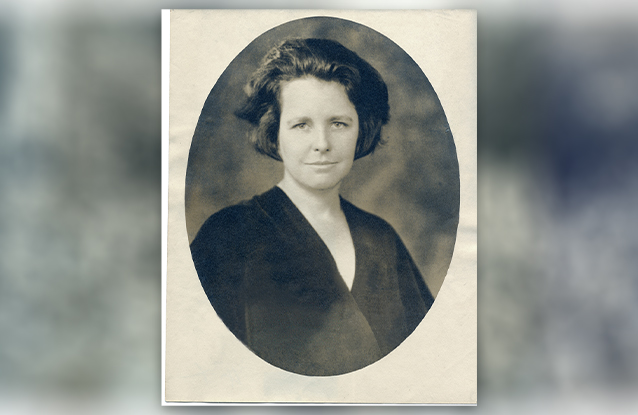

Carrie Pollitzer (1881-1974)

The eldest sister, Carrie, had a sense of purpose and resolve as strong as an iron bar. An educator who studied at several impressive universities—including Harvard, Columbia, Cornell, and Vassar—Carrie helped found the South Carolina Kindergarten Training School in 1908 and later became its assistant principal. The first of its kind, this progressive program educated teachers of preschoolers.

Carrie’s passion was for establishing women’s rights—of which, in the early 1900s, there were none. She enlisted herself in the battle for the passage of the 19th Amendment, which would give some women the right to vote, and worked hard for the cause. Carrie was a visible field lieutenant in the suffragists’ army, out in front and leading the battle cry. Throughout much of the year 1912—early in the campaign—she operated a booth on the corner of King and Broad streets, where she handed out pamphlets educating citizens about women’s suffrage.

The old order would surely change, Carrie argued, and she was right: “the women of today,” she said in one speech, “as the coworkers, partners, and guardians of a precious civilization, are to be accorded the opportunities accorded only to men.” In 1917, the College of Charleston unknowingly handed her a case in point, where, after her persistent petitions as a member of the Charleston Federation of Women’s Clubs, the board conceded that white women could be admitted to the college, but only if money could be found to pay a matron and construct a separate lounge. The board thought the task was a fool’s errand, but Carrie and her volunteers proved them wrong. They needed $1,500, and by the end of summer, the fund was oversubscribed. In September 1918, 13 women were enrolled at the College of Charleston.

Mabel Pollitzer (1885-1979)

Like Carrie, Mabel followed a less-traveled path, committing herself to the suffragist cause. Both sisters believed that education was the key to the advancement of women. Mabel, too, became a teacher, but an unconventional one. She left Charleston for New York to study at Columbia University, where she double majored in biology and education, and returned home to teach at Memminger Normal School (then a high school for white girls), where she remained for more than 40 years. Eventually, she became the head of the science department and created the first biology curriculum in South Carolina. Her Department of Natural Sciences, as it was known, covered botany, zoology, and physiology, as well as health and sex education.

Mabel was a popular teacher whose students came to her wanting to know things “that their mothers wouldn’t tell them.” She later recalled that these young girls “often got their engagement rings right along with their class rings. And I would tell them, ‘If they wanted to buy a refrigerator, they would look at not just one, but examine many before they decided. But when it came to...love, oftentimes it was the first one who asked them, without knowing about others.’” Her Child Development and Family Relations course, taught to high school seniors, became one of the first sex and family health education programs in the state.

With Carrie, Mabel worked for the National Woman’s Party—which eventually evolved into the National Organization for Women. She was the state chair of the party as well as its publicity director. Along the way, she became instrumental in establishing the Charleston Free Library. And in 1972, well into her 80s, she was still campaigning, with her sisters, for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, which passed that year but has yet to be ratified by all states, including by South Carolina.

Anita Pollitzer (1894-1975)

It was Anita, born in 1894, who had the broadest vision of all the sisters, was the most ambitious, and the one who arguably made the greatest sacrifice.

From a young age, Anita had shown a strong aptitude for painting and drawing. In 1913, following family tradition, she left to study at the School of Practical Arts at the Teachers College of Columbia University. There, she became friends with an austere-looking young classmate named Georgia O’Keeffe. They were an odd pair—the imperious, older-than-her-years O’Keeffe, dressed always in tailored suits and long white shirtwaists, and Anita, almost childlike in stature, her dark hair spattered with paint, as she swept about the room, flying and fluttering everywhere with the nervous energy of a bird caught in a chimney.

hey struck up a friendship when they learned of their many shared interests, including suffrage. Right away, Anita suggested O’Keeffe join the National Woman’s Party, taking their stand on voting rights for women. Both would maintain their memberships for decades to come, Anita eventually leading the organization and O’Keeffe serving on its board.

They also took a demanding regimen of art classes at Columbia—particularly those taught by Charles Martin, who pushed both women’s imaginations to their limits. In a 1950 article for The Saturday Review, Anita recalled a galvanizing moment in her and O’Keeffe’s fledging art careers—the day that Martin took the two women aside and set them up to work experimenting with oils on still lifes and flower studies, while the rest of the class kept at their elementary sketchings of plaster casts and other, inorganic subjects.

O’Keeffe finished her degree, but lacking any great prospects she trudged off on a nomadic journey through a series of rural teaching posts in the Southeast and Southwest. Throughout this time that O’Keeffe described as a hapless exile, Anita kept her friend’s spirits raised through an almost continuous epistolary dialogue on matters ranging from birth control and communism to cubism and prohibition. Anita’s letters were a lifeline to the real world of friends “who love life as we do, who read and think, who feel music and art to be as necessary as food and drink.” Anita also dispatched cultural care packages to O’Keeffe in such far-flung places as Canyon, Texas, and other points unknown—art journals, the latest issue of The Masses, and Susan Glaspell’s novel Fidelity. Their letters tell the story of a deep and abiding friendship that would later, sadly, fall apart.

“I’m floundering about as usual,” O’Keeffe would write to her friend. “The colors I seem to want to use absolutely nauseate me, then I made a crazy thing last week—charcoal—somewhat like myself … I am lost, you know.” Anita would not let her friend get herself down: “Keep on working this way,” she urged, “like the devil. Hear Victrola Records. Read Poetry. Think of people & put your reactions on paper.”

Anita, Mabel, and Carrie first met Alice Paul, the co-founder of the National Woman’s Party and architect of both the 19th Amendment and the Equal Rights Amendment, when she came to Charleston on a whistle-stop tour of the South to rally support for suffrage.

Ironically, it was Anita, not O’Keeffe, who first showed artistic promise at Columbia, most importantly to Alfred Stieglitz, the man who single-handedly pioneered photography as an art form in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and who introduced America to the works of Picasso, Matisse, and Cezanne at his fabled Gallery 291 in Midtown Manhattan. Anita was a regular there, and Stieglitz became her mentor in Modernism. She brought about one of the most storied conjunctions in American art when, on a rainy Sunday afternoon in January 1916, she showed Stieglitz some drawings by O’Keeffe. The master looked at her lyrical sketches and judged them to be “the purest, finest, sincerest things that have entered 291 in a long, long time. At last,” he exclaimed, “a woman on paper!”

Thus began a charged and fruitful relationship between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, for which the former, appropriately, gave Anita credit: “There seems to be nothing for me to say except—thank you—very calmly and quietly,” she wrote. “But how on earth am I ever going to thank you or get even with you?” O’Keeffe returned to New York in 1918 to become Stieglitz’s student, and soon, his lover. They were married in 1924, by which time the interests of the two former classmates and close friends had diverged. O’Keeffe started on her journey to greatness, while Anita’s potential as an artist—Stieglitz called her “one of the few real 291s—a creative force”—went unfulfilled when she gave up painting to campaign for women’s rights.

Anita, Mabel, and Carrie first met Alice Paul, the co-founder of the National Woman’s Party and architect of both the 19th Amendment and the Equal Rights Amendment, when she came to Charleston on a whistle-stop tour of the South to rally support for suffrage. Paul and other women, who had been imprisoned for demanding voting rights, traveled the country by train, dubbing the tour the “Prison Special,” to speak of how they had been treated after being arrested for picketing. At one notorious trial, 16 suffragists were handed a seven-month sentence to be served at a workhouse in Occoquan, Virginia, where they were threatened with “the brace and bit” in their mouths and straitjackets on their bodies if they refused food.

At once inspired and appalled that such a thing could happen in a democracy, Anita abandoned painting and drawing to join Paul’s contingent. She quickly rose to the rank of trusted second-in-command and spent the next two years crisscrossing the country speaking in support of the 19th Amendment.

Anita defied traditional models and shattered all stereotypes. When she married in 1928, she retained her maiden name. She had her own career. She made it impossible for editorial cartoonists to lampoon her—she was anything but the hatchet-jawed, severe-looking crusader of demeaning newspaper caricatures. She was “easily moved by beauty everywhere, in a painting or in nature,” a friend once said, “and she was deeply touched by sadness or injustice in the lives of others.” She managed to be at once a patrician and a democrat.

In 1919, Anita helped change the course of the country. That year, the 19th Amendment passed Congress, but it still needed ratification by 36 states in order to become law. Anita made that happen by taking on the one obstacle that blocked the measure’s passage—a stubborn, 24-year-old senator from Tennessee named Harry Burn. During a six-week seesaw struggle in 1920, Burn held up the amendment’s ratification while he struggled to reconcile his essential liberal-mindedness with the pressures from his Southern constituency, most of whom were openly chauvinistic and didn’t see why anyone would be otherwise. But Burn succumbed to Anita’s intellectual power—and her charm. He changed his “no” vote to “yes” in response to her pleas, and women officially got the vote. But Anita didn’t stop there. She and the National Woman’s Party—which she would lead in the 1940s—pushed for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, introduced in every session of Congress since 1938.

Anita’s crusade was an expansion of the understanding and devotion she had earlier shown O’Keeffe, part of a wider commitment aimed at improving women’s lives throughout the world.

The Pollitzer sisters lived their lives with courage and determination to help provide women with the right to live more conscious lives, to be recognized not merely as extensions of their husbands, but as individuals.

There is a later story, from the last years of Anita’s life, about her relationship with O’Keeffe. In the 1950s, Anita and her husband, Elie Edson, lived in a cramped apartment on West 115th Street. Crammed with teetering bookcases and wooden crates of jazz records stacked in corners, their home was a classic salon—a meeting place for artists, writers, and university professors allied in progressive causes.

In the midst of this controlled chaos, Anita would talk about the biography of O’Keeffe, which she was then writing with her friend’s approval. It became the great project of Anita’s life, and she toiled on it for years, spending time with O’Keeffe in New Mexico and visiting the artist’s childhood home in Wisconsin. But when Anita finally completed the book in 1968, O’Keeffe withdrew her support and refused to allow it to be published. She told Anita, “You have romanticized me. I do not recognize myself.” Anita was crushed by her friend’s rejection.

However grieved she was by her falling-out with O’Keeffe, prior to her death, Anita channeled even more energy into a Constitutional amendment to include the equality of rights she had worked for all her life. In a somber reminder of the demise of their relationship, just after Anita died in 1975, O’Keeffe’s lawyers informed Anita’s heirs that the artist wanted the return of a painting she had given to her.

Like Mabel and Carrie, Anita was, fundamentally, a crusader driven by unswerving vision. The Pollitzer sisters lived their lives with courage and determination to help provide women with the right to live more conscious lives, to be recognized not merely as extensions of their husbands, but as individuals. They made a difference, and even four-plus decades after their deaths, their legacies live on.