A look at how these insitutions are evolving to best serve the city

In midsummer 2020, the Aiken-Rhett House's soaring ceilings, wide piazzas, and huge, breeze-welcoming old sash windows proved that early 19th-century design could hold its own against Charleston's swelter, which was welcome news for those who came to view Fletcher Williams’s “Promiseland.” It was hot out all right, but Williams’s installation was even hotter, and the juxtaposition of the young artist’s contemporary works on paper and sculptures with the venerable manse’s still-grand yet hauntingly unrestored rooms was powerful. Williams’s work, a series featuring fence pickets in dialogue with each other (many texturized using paint-soaked Spanish moss), wrestled with questions of who’s in and who’s out, the role of barriers and boundaries, of protection and privacy in the face of privilege, and, yes, preservation.

That “Promiseland” was sponsored by Historic Charleston Foundation (HCF) and presented in one of its premier house museums could be considered a shift worthy of an earthquake bolt. This was not the Charleston Antiques Show with its polished silver and mahogany consoles of storied provenance; this was not a house and garden tour showcasing elegant architecture and building craftsmanship. Rather, the exhibition explored the provenance of long-festering societal wounds in a place patinated with that injustice. In the suffocating, simmering George Floyd summer, this was preservation as provocation.

Old age has its perks, and as hosting “Promiseland” suggests, HCF, celebrating its 75th anniversary this year, is using its maturity and mensch status to turn up the heat on issues beyond the preservation of beautiful old buildings—an approach that, fittingly, has a history at this history-focused organization. The backdrop for “Promiseland” is case in point: the Aiken-Rhett House, one of HCF’s two museum houses, has long been lauded as an innovative museum model, in which the foundation embraced stabilization and interpretation with a “preserved-as-found” strategy. Visitors see both the architectural wonder and the obvious, unmasked disparity between the refined Dijon-hued manor and the surviving kitchen house, laundry, and stables, where enslaved people lived and labored in close proximity yet very different circumstances.

As this interpretative philosophy demonstrates, the foundation understands that preservation is largely an endeavor of storytelling, and also truth-telling, about a painful past. According to Winslow Hastie, president and CEO of HCF, it’s also about creating new stories, about shaping the next narrative for Charleston. “We can’t celebrate a major anniversary and not look back, particularly because we’re a preservation organization focused on history,” Hastie says. “But for me and for the foundation, it’s really about looking forward, about where we’re headed—about identifying challenging issues facing the region and using our resources to address them in the best way possible.”

Hastie, 49, is no Pollyanna about those challenges. A Charleston native whose family owns the historic Magnolia Plantation, he, both personally and professionally, has been steeped in all things old, precious, and complicated. Hastie worked as the City of Charleston’s senior preservation planner before joining HCF in 2006, where he served as chief preservation officer before being appointed Katharine (“Kitty”) Robinson’s successor as president and CEO in 2017. Robinson had been affiliated with the nonprofit for four decades, and led it for 17 pivotal years. “I’ve always been interested in how we make preservation relevant to broader audiences. The tendency to be backward-looking or to be seen as an obstruction for change has always been problematic for me,” Hastie says. “Preservation is about the future and how we evolve as a community. It’s about how we manage change, not how we stop it.”

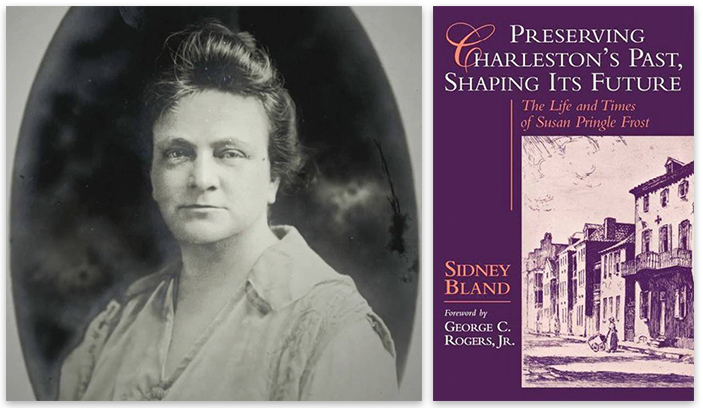

Susan Pringle Frost founded the Society for the Preservation of Old Buildings (today’s Preservation Society of Charleston) in 1920.

Revolving & Evolving

When most effective, the foundation’s effort to manage change has always been done in partnership with other organizations; in fact, HCF’s own origin story underscores this. As Sidney Bland recounts is his book, Preserving Charleston’s Past, Shaping Its Future: The Life and Times of Susan Pringle Frost (Praeger, 1994), the idea for a foundation that would complement the work of Frost and her grassroots Society for the Preservation of Old Buildings (founded in 1920, now known as the Preservation Society of Charleston) first arose from within membership of PSC.

For its first 25 years, the PSC made headway rescuing and rehabbing crumbling old “gems,” buildings long neglected in the economic doldrums post Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Great Depression. But the need exceeded the organization’s reach. According to Bland, civic leader Robert Whitelaw and architect Albert Simons, members of the PSC’s survey committee, advocated for a new organization to initiate a revolving fund and broaden the scope “beyond just fixing up one or two houses....” In 1947, Whitelaw became one of the founders of Historic Charleston Foundation, which, under the leadership of Frances Edmunds, set about doing exactly that.

“We’ve had a partnership from the earliest stages of their existence,” says Brian Turner, who took the PSC helm as president and CEO in April 2022. The main difference between the kindred organizations is that PSC is a membership-based organization, governed by a board elected by its members, and HCF is not. “We’ve developed this character of being a scrappier, citizenry-based advocacy group,” says Turner, while HCF also represents and engages the community but “has emerged to use different tools in the preservation tool kit.” And HCF’s primary tool, initially at least, was the revolving fund.

The foundation’s Edmunds Endangered Property Fund, established in 1957, was the first of its kind in the nation and has since become a model emulated by preservation groups across the country. By purchasing at-risk historic properties, stabilizing them, reselling them with protective covenants, then using those sale proceeds to buy other at-risk properties, the revolving fund has been hugely successful in revitalizing entire neighborhoods. HCF’s Ansonborough Rehabilitation Project has rehabilitated and protected 80-some buildings in that neighborhood alone. “But market forces have changed, and the private real estate market is now purchasing even the most dilapidated properties, making the revolving fund model basically defunct,” notes Hastie. “We’ve worked ourselves out of a job, which frankly is what we want.”

The question now is how will the fund evolve—“what’s the next generation of it?” asks Hastie, particularly as those same market forces that have made the revolving fund model less viable have made gentrification and housing affordability issues more dire. The fund and numerous other preservation and planning initiatives have created a goose-and-golden-egg conundrum. “Charleston’s success as a tourist destination and place to live and relocate businesses is predicated on our preservation ethic and the work of many prior generations. We’re victims of our own success,” Hastie says. So over the past several years, under Robinson’s leadership and now Hastie’s, HCF has been broadening the perspective regarding what is worthy of preservation, with the PSC joining in and helping shape that conversation. “Clearly, the culture and soul of a place is as important as the built environment,” Hastie affirms.

Gentrification, housing affordability, density, flooding and water management, transportation, tourism management, heirs’ property issues—the HCF’s current community issues list goes far beyond building preservation. In recent years, they’ve sponsored the Dutch Dialogues to address sea level rise and flooding. Partnering with the City of Charleston, they’ve created a Community Housing Trust to chip away at affordable housing. And they’ve hosted numerous public forums and charettes to bring together experts and concerned citizens on topics from tourism management to transportation. “HCF remains known for its willingness to collaborate in working for the betterment of the community,” says Kitty Robinson, who created the Community Room in the Missroon House, the organization’s headquarters, as a resource for other groups and to bring different entities together.

At their most recent public forum, an Advocacy Forum in May—one of the foundation’s 75th anniversary events, the discussion was framed around the pending revision of the City of Charleston’s “Peninsula Plan,” slated to be updated this year. The current plan dates from the last millennium (1999), and since then, the peninsula’s residential population, particularly its African American population, has seen a precipitous drop, falling by nearly 5,000 residents from 2010 to 2020, according to the 2020 US Census. In Charleston County, it takes at least a six-figure income to afford a typical single-family home, and the metro area’s average monthly rent topped $1,600, higher than the national average. “This is starting to really affect the fabric of our community,” says Hastie.

But panel discussions only go so far, and solutions, particularly related to mitigating gentrification and housing affordability, aren’t easy. Nor, Hastie admits, does HCF have the inroads and infrastructure to work effectively in many of the most impacted neighborhoods. “To be completely candid, part of the challenge is that we lack the networks in many of the African American communities and lower-income neighborhoods that we have elsewhere,” he says. While HCF has had some successes in those areas in recent years, including rehabilitating freedman’s cottages in North Central and creating the Romney Street Urban Garden, “we need to do more to put in the time, energy, and build the trust,” he adds. “Let’s be honest, the Black community has been swindled time and again, and trust is a big impediment. We can’t take a flash-in-the-pan approach.”

(Left) First Lady of Preservation: Frances Ravenel Smythe Edmunds, the first director of Historic Charleston Foundation, became a leading figure in the 20th-century preservation movement not only in Charleston, but in the nation. Under her visionary leadership, the revolving fund was established, resulting in preservation of the Ansonborough neighborhood (where she is pictured) and became a model replicated by other preservation groups; (Right) Enduring Legacy: Like Edmunds, Katharine “Kitty” Robinson (pictured at the HCF’s Nathaniel Russell House) first started as an HCF volunteer; she served 17 years as president and CEO. During her tenure, many events, like Charleston Antiques Show, and initiatives were established, including expanding the foundation’s reach as collaborator and convener on numerous civic issues.

Common Cause

But they can, and are, trying out new community-based tools, or evolved iterations of the revolving fund, to help keep long-term peninsula residents in their homes. First, HCF along with the City of Charleston and the nonprofit Charleston Redevelopment Corporation has created the Palmetto Community Land Trust, an entity that in essence buys land, thus removing single and multi-family housing from the open market, in order to convey ownership to long-term residents via a 99-year lease. By maintaining land ownership, the land trust can manage the price appreciation, retain the community value, recycle the subsidy, and preserve the land and affordable units for future generations.

Secondly, HCF in partnership with the City of Charleston and the Palmetto Community Land Trust, with support from the 1772 Foundation, has created Common Cause, a community loan fund providing below-market rates for those in the 60 to 120 percent area median income category who need assistance in maintaining their homes. Thanks to a $100,000 grant from the 1772 Foundation, matched by HCF and the Charleston Community Redevelopment Corporation, Common Cause is beginning with $300,000 for loans to assist those in owner-occupied historical homes with repair and rehabilitation projects. “Thankfully the 1772 Foundation is willing to fund pilot projects—often this is as much about finding out what doesn’t work as what does,” says Hastie. “But the issues are so acute on the peninsula, so anything we can do sooner here is critical.”

“Unlike some equally historic places, Charleston is still very much a working city, and ensuring that we have an adequate supply of affordable housing is key to preserving that part of our city’s character,” says Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg. “Working creatively with nonprofit partners like the Historic Charleston Foundation—and programs like the Common Cause loan fund and the Palmetto Community Land Trust—we can continue to balance the crucial need of maintaining housing accessibility and protecting the historic integrity of our neighborhoods.”

From trying out innovative solutions to tackle housing affordability, to staying on top of sea wall discussions, to ensuring the community is informed and engaged on the pending Peninsula Plan update, HCF is hardly slowing down at age 75. And with the city at a precarious moment—when development is rampant and major projects like Union Pier, Laurel Island, and Magnolia are on the horizon—the parallel efforts to preserve Charleston’s historic fabric and character while ensuring a livable future converge, not unlike the Ashley and Cooper rivers and like HCF and PSC, forces coming together to shape Charleston. “The foundation has been at the table and at the forefront of so many critical issues and initiatives over the years, from gifting the city its first Preservation Plan in 2015 to steering the Peninsula Advisory Committee under Mayor Riley, which initiated the Second Sunday program among other things, to being early and continual supporters of the International African American Museum,” says Robinson. “What an immense honor it’s been for me to be part of this organization that continues to shape the future of Charleston.”

Susan Pringle Frost and Frances Edmunds may have never envisioned what the Holy City would look like in 2022: cranes dwarfing church steeples, apartments rising along East Bay, hotels on nearly every corner, home prices in astronomical territory. It’s doubtful that they ever envisioned a contemporary art exhibit staged in parlors and outbuildings of the Aiken-Rhett House, but their tenacity endures as their legacy organizations keep watch, innovate, reinterpret, and stay creatively vigilant.

Charleston has long been at the forefront of historic preservation—the National Trust for Historic Preservation was established two years after HCF and more than 25 years after PSC was founded, notes Turner, who worked for the Trust before joining PSC. And today, the city remains ahead of the curve, at the cusp of a national trend in the world of preservation, says Hastie, “a shift from being about buildings to being more about people, neighborhoods, culture, all the things that are intangible but nonetheless vital.”

Before & After: This historical freedman’s cottage on Romney Street was fully restored by HCF in partnership with the City of Charleston, as part of HCF’s Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative. Next door is the Romney Street Urban Garden.

Celebrate 75!

For a list of upcoming HCF’s 75th anniversary events, including Women Who Impact Preservation, a free community day at the Aiken-Rhett House Museum, and the Mosquito Beach Oyster Roast, visit historiccharleston.org.

HCF Milestones: 75 years of preserving the city’s architectural and cultural fabric

Learn more about the Nathaniel Russell Kitchen House Project:

Watch our 2019 video about the Dutch Dialogues to address sea level rise and flooding:

Photographs courtesy of Library of Congress & Historic Charleston Foundation

Photographs by (Hastie) Marykat Hoeser, (house in time line) Julia Lynn, (Robinson) Sully Sullivan, & (cityscape) Sean Pavone