Persons was credited with identifying a new genus of marine reptile

Age: 37

Lives: West Ashley

Education: Bachelor’s degree from Macalester College, master’s and doctorate’s degrees from University of Alberta

Career: Assistant professor of geology at College of Charleston, curator of the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History

Pets: Rescue mutt, Hannah, and Boston Terrier, Franklin

Scott Persons’s career ambitions solidified at age two, when his father read him The Big-Little Dinosaur. By 12, he’d convinced his parents to covertly send their underage son to a paleontology camp for teenagers. During high school, he returned to that camp near Glenrock, Wyoming, where he’d ponder the jaw of an aquatic dinosaur (dubbed “Harold”) that always struck him as being different.

Nearly 20 years later in 2022—after pursuing paleontology through undergraduate, master’s, and doctorate degrees—the Tuckasegee, North Carolina-bred scientist was credited with identifying old Harold:

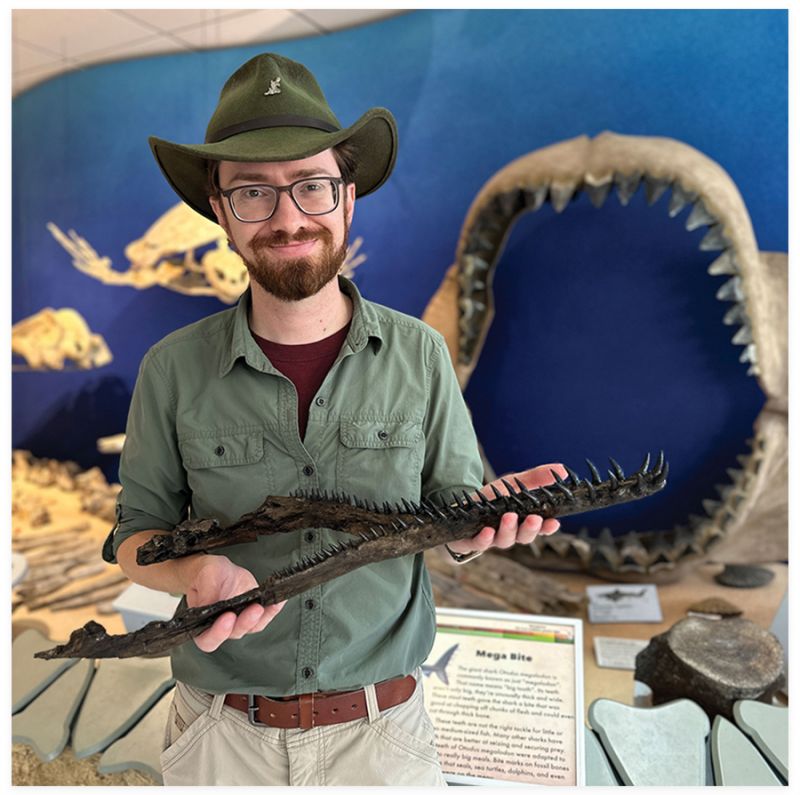

Serpentisuchops, a new genus of marine reptile. A cast of the dinosaur’s jaw sits in his office at the College of Charleston, where Persons is an assistant professor of geology and the curator of the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History. We walked through the museum with Persons to hear about his passion for prehistory and to discover what lies beneath Charleston’s sandy soil.

CM: How has the Serpentisuchops discovery changed your career?

SP: It’s contributed to the tremendous support we’ve had here at the college. We’re attracting extremely high-quality students who will likely graduate having made real contributions to a scientific publication.

CM: Why base yourself in Charleston as a paleontologist?

SP: The Mace Brown Museum has a staggering number of specimens, most of which were discovered locally. We have whole cases of specimens donated by local amateur collectors. For example, we have a mastodon that was discovered in a drainage ditch near Dorchester Road in North Charleston in 2013.

CM: How much do you think is still out there?

SP: It’s not a matter of running out of fossils in the Lowcountry. It’s a matter of resources—how many people do we have to dig and how much time can they spend digging?

CM: What would the Charleston peninsula have looked like in prehistoric times?

SP: The most exciting time might [have been] about 12,000 years ago. The shoreline would be much further out—it would be a much longer drive out to Folly—and you would see a mostly familiar cast of flora, like palmetto trees, but munching on them would be ground sloths, mastodons, and mammoths. Lurking in the shadows would be saber-tooth cats, wolves, and bears. And hanging out in the swamps would be alligators, just as they are today.

CM: When you go to the beach, are you looking for shark teeth and vertebrae?

SP: I’m absolutely out there poking along the shoreline. And rest assured, we are in no danger of running out of shark teeth.

WATCH Scott Persons discuss ancient marine mammals in a preview of an online course he taught while at the University of Alberta