See the final projects of ACBA seniors presented during a special capstone reception

Carolyne Chardac radiated a 10-megawatt smile as she gave an animated description of her wall-sized creation, a white-and-gilt plasterwork inspired by the 18th-century apartment of Madame du Barry at Versailles. Ornate and elegant, the work infuses all 26-by-eight feet with the aspects of design that drew Chardac to the American College of the Building Arts (ACBA): skilled plasterwork, the decorative arts, architectural elements, and historical authenticity. Knowing her project will be permanently installed at her soon-to-be alma mater only amplified her enthusiasm.

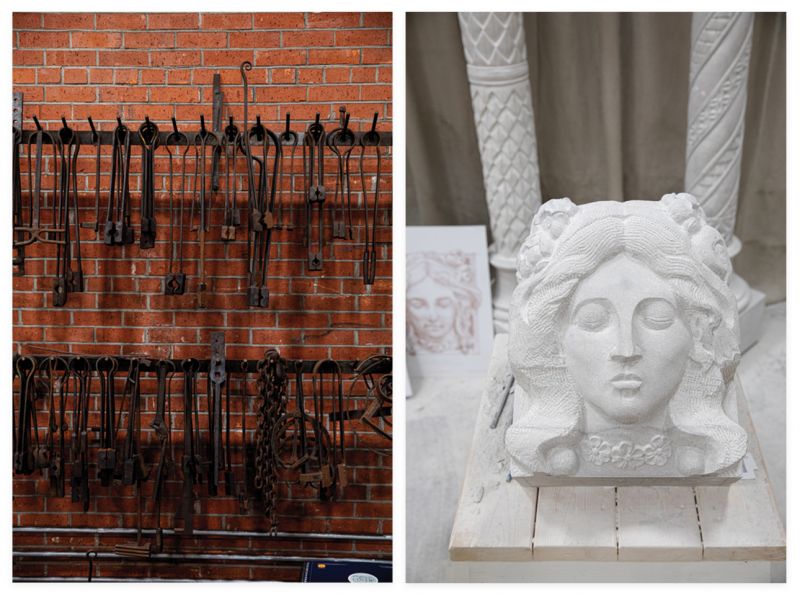

This was Chardac’s capstone presentation, the culmination of four years at ACBA, a private, four-year, liberal arts and sciences college that grants bachelor’s and associate’s degrees in applied science in six specializations: architectural carpentry, plaster, timber framing, stone carving, blacksmithing, and classical architecture and design. On this evening in May, 16 other students’ projects were also on display for a crowd of admiring faculty, family members, guests, and fellow students at the school’s Meeting Street campus. The event launched the class of 2024’s graduation weekend and underscored the triumph of the college achieving its 20th anniversary as the sole educational institution of its kind in the US.

“What I tried to do is bring Paris to Charleston,” explained Chardac, a 57-year-old mother of two grown sons and former human resources specialist for a textile company in Atlanta. “We have so much English plasterwork represented here, I thought it was time we had some French as well.”

Since the fall semester, these ACBA seniors had conceived, designed, planned, and constructed their projects, individually investing upward of 300 hours of sweat equity. This opportunity to synthesize theory and academic study with hands-on skills is unique to the ACBA curriculum and exactly why Chardac and her fellow capstone presenters—including Paul Reilly, whose hand-forged, wrought-iron gate features a Roman-inspired arch, and Michael Vanderlip, a graduate in classical architecture who designed a Versailles-esque orangery—spent the last four years here mastering the skills, methods, and perspective necessary to become successful artisans.

Recent graduate Carolyne Chardac (above, left) beside her 2024 capstone project; she modeled it after Madame du Barry’s 18th-century apartment at Versailles.

W.E.B DuBois believed that the object of education is not to make men carpenters, but to make carpenters men. Serving both practical and creative goals, ACBA achieves both, for men and women.

The college’s genesis traces back to 1998, when a team inspired by renowned Charleston blacksmith Philip Simmons and led by young preservationist John Paul Huguley determined to fill the gap in skilled local craftsmen. That void became critically apparent nearly a decade before when Hurricane Hugo left homeowners scrambling to find skilled tradesmen to repair damage to their historic homes—many resorting to bringing in artisans from Europe to restore piazzas, carved stone cornices, and plaster moldings. Huguley saw the need and opportunity: he developed a concept to integrate the summer building-crafts training program begun six years earlier by the Historic Charleston Foundation with a community workshop specializing in old-world artisanal trades.

Modeled after the 600-year-old French guild apprenticeship program Les Compagnons du Devoir, the School of the Building Arts (SoBA) would produce a new, committed generation of skilled craftspeople. Thanks to pivotal support from then-Mayor Joseph P. Riley and community leaders Senator Herbert Fielding, Nancy Hawk, and Pierre Manigault, SoBA was launched in 1999. The school’s mission: to “educate and train artisans in the traditional building arts to foster exceptional craftsmanship and encourage the preservation, enrichment, and understanding of the world’s architectural heritage through a liberal arts education.”

The first classes were held at various locations around town, including the crumbling Old City Jail on Magazine Street, which became the school’s home base. The idea was that the iconic circa-1802 structure would be a living lab for students, who could hone their timber-framing, masonry, stone-cutting, carpentry, and blacksmithing skills while shoring up and restoring the Robert Mills-inspired building.

While the SoBA students did help stabilize the jail, the nascent school’s own stability presented other challenges. Construction projects are notoriously complicated, and that’s especially the case when building a college that’s the first of its kind in the country. Teaching esoteric trades like plasterwork and timber framing is time-intensive and hands-on, often requiring one-on-one instruction, which is expensive. In addition to fundraising, SoBA was pursuing accreditation to become a full degree-granting institution. “It’s a rigorous process, one that requires many steps and takes many years,” notes Huguley. “We set our goal, as accreditation would open avenues of financial aid and allow us to achieve a more robust enrollment. It was a critical building block for the longevity of the college.”

In 2005, the school hit that goal and was reborn as the American College of the Building Arts, a four-year program with a liberal arts curriculum—i.e. a modern college specializing in old-world crafts. Four years later, amid the recession, the institution awarded its first degrees to seven students.

“The curriculum that the school put together was, from the beginning, an outstanding one, based on a number of years of research,” says Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Colby M. Broadwater, a former board member who was named ACBA president in 2008 and is credited with having led the college through financial hardships. “I saw something there that was inherently right. My goal was to grow the school academically and to perfect a business model to support it.”

The Big Reveal - On May 17, after months of conceptualizing, planning, and executing, 17 ACBA seniors presented their final projects to faculty, family, and guests during a special capstone reception, kicking off their graduation weekend. >>VIEW THE GALLERY HERE

By all accounts, Broadwater and the board have done just that. Tuition has held steady at $20,000—modest by today’s higher education costs. In 2016, thanks to major donations from San Diego-based Parallel Capital Partners and Russell and Betty Joan Hitt, founders of HITT Contracting, the college began its move into a new, expanded campus on Upper Meeting Street, where the once-forlorn 1897 Trolley Barn is now the college’s spacious, versatile, state-of-the-art home after a $6-million renovation. The move has allowed for curriculum expansion, with the addition of classical architecture and electives in decorative finishes. A new, dedicated blacksmithing outpost is in the works on Upper King Street, next to Redux Contemporary Art Center.

For Christina Butler, professor of historic preservation and architectural history who has been on the teaching staff since 2015 and is now dean of faculty, the expansion and newly unified campus has opened new doors. “Before, we couldn’t accommodate the student numbers we have now,” she says of the enrollment projected to reach 150 for the upcoming fall semester. “As a preservationist, I love adaptive use. We knew when we moved into the new building in 2016 that there were different ideas on how best to utilize it, and a lot of heart and soul has been invested in it. We want to keep doing what we think is a unique form of education and keep trying to perfect it.”

Mayor Riley envisioned ACBA becoming Charleston’s gift to America, but it is no less a gift to the city itself. In many cases, so are its graduates. Four years at ACBA taught Guyton Ash more than the elements of timber framing; it taught him discipline and dedication. “What it meant to me was unlocking my potential as a craftsman and as a business owner, giving me the training and confidence to go out and do it,” says the 2011 graduate, now co-owner of the Charleston-based firm Artis Construction.

Ash went into business for himself upon graduating, producing furniture and high-end trim packages, but was determined to establish a more formal business focusing on historic preservation. “After three years working for others, my business partner and I started Artis Construction,” adds Ash, whose company name derives from the Latin word for “craftsman.” “While we also do new construction, our bread and butter is historic work in downtown Charleston, where we’ve carved our niche.”

Like all ACBA students, Ash benefitted from externships, working up to 10 weeks in a professional setting during the summers of his freshman and sophomore years. The college requires that these “apprenticeships” be completed for students to continue coursework the following year. “Guyton is like a poster boy for the success of the college, having developed a very successful business in Charleston,” says Butler. “He employs our alums and takes on others as externs.”

Recent externships have enabled students to work locally doing interior renovations at the Powder Magazine, repairing gravestones at Circular Congregational Church, producing and installing artist Fred Wilson’s wrought-iron Omniscience sculpture at the Gibbes Museum of Art, and constructing new bases for the cannons at Charles Towne Landing. Opportunities outside the city have encompassed repairing windows in the Oval Office of the White House, restoring stonework in England’s Lincoln Cathedral, repairing the ironwork of the US Capitol dome, and rebuilding a garden folly at Germany’s Hundisburg Castle, as well as work at Monticello and Mount Vernon. Increasingly, ACBA students have been involved in projects starting from the ground up, such as the timber-frame welcome center at the 18th-century Drayton Hall estate in West Ashley.

(Left to right) Late blacksmith Philip Simmons, who inspired and helped found the school; After years of holding classes in the cramped quarters of the Old City Jail, ACBA moved into the spacious and newly renovated circa-1897 Trolley Barn on Meeting Street in 2016; Blacksmithing professor Abe Pardee works with ACBA senior Emmett Sullivan; the school will unveil its new forge on upper King Street this month.

Typically, French paneling, called “boiserie,” is made of wood and gilded, but Chardac composed her capstone project of plaster. “It’s the same result with a different material, using very simple tools and no molds,” she explained. Chardac noted that she has already formed her own company, Atelier 11 Plaster and plans to work hand-in-hand with the French plasterwork company Auberlet et Laurent, where she externed last summer in Paris, assisting with installations, sculpting new designs, and casting and running moldings for clients.

Glowing beside her elegant creation, she credited Angela Cabán, ACBA professor of plaster and decorative finishes, for exposing her to the art of gilding—“Angela really opened a new door with what I could do with plaster”—and Auberlet et Laurent North American president Baptiste Lebufnoir, who attended the capstone reception, for helping guide her on her project. Impressed with the results, the company recently appointed her as their US plaster contact for installation and potential bids.

“What I learned at Auberlet et Laurent is traditional French ornamental plasterwork, which differs in design and technique, is truly handcrafted, and sets a high bar,” said Chardac, who came to ACBA four years ago looking for a life change. She found it, thanks to new yet very old skills that have become for her a personal capstone of sorts. “None of this would have happened without ACBA.”

WATCH: Meet blacksmithing grad Sean Berube and learn more about his capstone project

WATCH: Check out architectural carpentry grad CL Fristoe’s capstone project in process