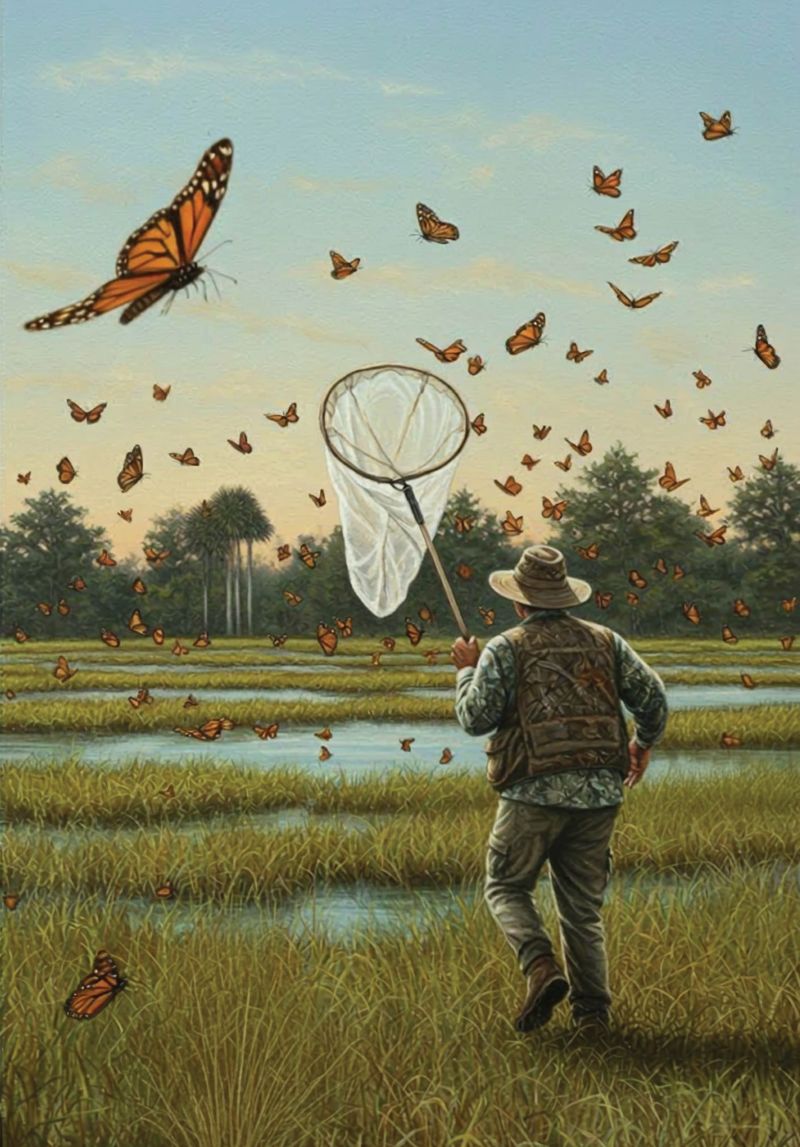

If you see a man fully dressed in camouflage emerge from the woods on the north end of Folly Beach, don’t be alarmed—as long as he’s holding a net on an eight-foot-pole. It’s Billy McCord, a semiretired biologist and the Southeast’s preeminent monarch butterfly expert. Now 72, McCord captures, tags, and releases around 2,000 monarchs each year, reaching a grand total of 55,000 butterflies since 1996, when the tiger-hued insects first stole his attention from his fisheries career studying sturgeon and shad with the state Department of Natural Resources.

Monarchs made headlines last December, when the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed classifying the species as “threatened,” one step below endangered. But McCord says that’s mostly due to the dramatic reduction in the flyway over the central US as monarchs head south to winter in Mexico. Government subsidies for ethanol from corn and soybeans have vastly reduced the acreage of natural grasslands where native milkweed grows in the Prairie States, leaving butterflies without a food source on their journey. But apart from temporary die-offs caused by extreme cold like this January’s rare snowstorm, the Atlantic population of monarchs is relatively stable, says McCord.

He would know—the biologist discovered that many of the Lowcountry’s monarchs spend the entire winter here, rather than migrating to Florida or the Caribbean, as previously believed. But that doesn’t mean our local monarchs are without threats. We chatted with McCord to get the latest on his research and ongoing passion.

CM: What’s it like when you recapture a monarch that you’ve already tagged? Is it a “prodigal child” kind of feeling?

BM: It is. If I see a tag, I try my hardest to catch [that butterfly], because then I can use that information to figure out how far it moved in the time between captures. Recaptures are how I get information about what they’re doing or where they’re spending the winter. But we still don’t know if they go north from here. Until we get more tag recoveries, we don’t know a whole lot about their movements.

CM: Is there a secret to catching a butterfly?

BM: You need to swing with some momentum, because they can dive down really quickly to get away. I wear camouflage because they can see colors and movement much better than we do. Their lives depend on that. They’re poisonous to vertebrates like birds, so their main threats are insects like praying mantises and spiders.

CM: Are the monarchs found inland during the summer different from the ones we see on Folly Beach during winter? And are those different from those that migrate to Mexico?

BM: My guess is that the ones that migrate to Mexico are genetically different from the ones that migrate down the Southeast coast. I’ve helped [the state Department of Natural Resources] with [ongoing] research that’s using leg clippings to test for genetic differences. Another thing I’ve noticed is that the monarchs that breed in our swamps are smaller, on average, than the ones that migrate here in the fall. I think it’s because their habitat gets flooded, so the caterpillars in the swamps get stunted when food is not available.

CM: What should people do if they want to encourage monarchs in their yard?

BM: Naturalized nectar plants like lantana, and even dandelion flowers, are great for monarchs. Our winter monarchs depend on landscaping plants like loquat and Japanese fig, because there are not that many native plants that bloom in the winter. Unfortunately, a lot of well-intentioned people plant milkweed that’s not native to South Carolina. It’s often marketed at garden centers as butterfly-friendly, but the tropical milkweed encourages a protozoan parasite that kills monarchs.

Mosquito control is the other culprit. Patriots Point used to be one of my favorite places to go tag monarchs, but now they host so many events and spray so frequently that there are hardly any monarchs there.

CM: Where can people find monarchs in the wild?

BM: By late spring, I start looking in cypress/tupelo swamps to find breeding monarchs, because that’s where milkweed grows. Apparently, the females can smell it from miles away. I catch them all summer in the Francis Marion National Forest and in forests west of the Ashley River. They’re in every major river drainage in the state. Monarchs are much more widespread in South Carolina than people think.